Andrew Jillions joins us once again to consider the legality and justice of Kenya’s incursion into Somali territory last week. This post is the first of two on the subject, so keep your an eye out for the second piece tomorrow. Enjoy!

Nominally at least, the Kenyan incursion into Somalia was triggered by the al-Shabaab terrorist threat. As Kenya’s internal security minister put it on the eve of the intervention, this is a war of self-defence: “the government is taking robust measures to protect and preserve the integrity of the country by invoking Article 51 of the UN Charter”. The Minister for Defence went on to clarify that Article 51 grants “the right to pursue the enemy through hot pursuit and try to reach them wherever he is”.

But does this really meet the threshold for a war of self-defence? Or is it better thought of as part of an emerging law of enforcement? And where, pray tell, does the humanitarian crisis in Somalia fit into this?

Threshold Test 1: Self-defence

There are some issues with the Kenyan claim to be acting in self-defence. Namely, al-Shabaab’s incursions weren’t of sufficient seriousness to trigger the right of self-defence. Even if the spate of recent kidnappings and deaths could be decisively attributed to al-Shabaab, and even if we took into account the other 8 instances of aggression cited against al-Shabaab, it would still not be enough to justify a violation of Somali sovereignty on the basis of self-defence. In other words, the Kenyan response fails the classic tests of necessity and proportionality.

The explanation that Vidan Hadzi-Vidanovi offers is that they’ve been reading Dinstein. Kenya was attempting to aggregate a number of ‘pin-prick’ attacks in order to reach the gravity required to trigger a war of self-defence, but haven’t quite pulled it off. Even if Kenya has been made more insecure because of al-Shabaab’s border operations, recruitment and dislocation of civilians, this not the same as being directly targeted.

Threshold Test 2: Unable or unwilling to enforce

But there is another possibility. This is that the Kenyan government had in mind the ‘unable or unwilling test’, the same test employed to justify the US violation of Pakistani sovereignty in the Bin Laden killing. In other words, they’ve been reading Ashley Deeks.

This is where the Kenyan government has been either ingenious or disingenuous, depending on how determinate you like your international law.

Where they describe the intervention as justified by a norm of ‘hot pursuit’, the growing scale of the conflict makes this a difficult justification to sustain. More appropriate is to see this as an intervention premised on Somalia’s structural inability or unwillingness to deal with the international terrorist organisation al-Shabaab. It’s not the kidnappings that justify the intervention. It’s the evidence that Somalia is functioning as a safe-haven for a terrorist organisation.

The crucial point about the unable or unwilling test in the context of counter-terrorism is that it looks for a pattern of cross-border aggression or the existence of a transnational criminal organization; far less crucial is the threshold or seriousness of that act of aggression. The effect of this is that when we look at the basis for intervention in Somalia, we should be looking at al-Shabaab’s status as a transnational criminal organization, and at the Somali government’s inability or unwillingness to deal with this transnational threat. There’s no real need to substantiate the claim to be acting in self-defence. The essence of the claim is that multiple violations of the type that did or could have permitted a hot pursuit can trigger a more sustained intervention on the basis of the unable or unwilling test.

A worrying development?

Part of the problem with using the unable or unwilling test to ground law enforcement is that it elevates state weakness into an actionable quality. Actually we can go further than this in the Kenyan case: it elevates an admission of weakness into an actionable event.

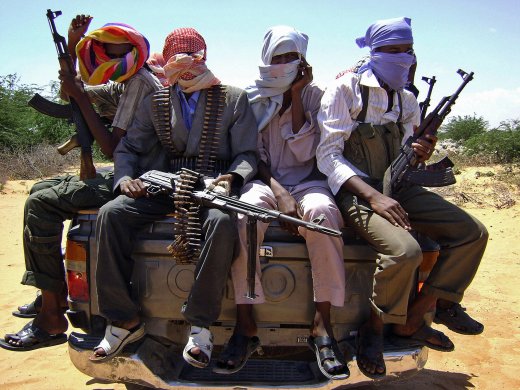

The humanitarian crisis, stoked by famine in Somalia, continues to ravage the region. (Photo by Oli Scarff/Getty Images Europe)

This is best seen in the ‘joint communiqué’ issued by the Somali and Kenyan governments the day after Kenyan troops had crossed the border. This doesn’t give any explicit consent to an intervention. Rather it commits both countries to coordinate and cooperate their actions against a common enemy. At the same time, it reaffirmed each countries territorial sovereignty. On the face of it, there is nothing in this document to suggest that it grants Kenya the right to intervene. Certainly Somalia’s president didn’t see it this way, if his characterization of the Kenyan offensive as an “inappropriate” violation of sovereignty is anything to go by.

However, the wording is telling. First it sets the scope of this cooperation in the context of the international community’s “inadequate, inconsistent and unsustainable support” that has undermined attempts to deal effectively with al-Shabaab. It further establishes that both states agree that al-Shabaab pose a terrorist threat to Kenya, to humanitarian operations, and to border security. This doesn’t amount to consent per se, but it does read as an admission of failure, an admission of an inability to deal effectively with a transnational threat to peace and security. Placed in the context of the unable or unwilling test, this admission of failure seems to be equated to an authorization to intervene.

This sets a dangerous precedent. There are too few criteria specifying how this enforcement power should legitimately be used, and too many cases where weak statehood could potentially trigger a right of intervention. There are any number of areas where the international community relies on states admitting their weakness, for example in allowing development or humanitarian aid and institutional building. But the use of the unable or unwilling test in this way is a potential disincentive for that admission of weakness. In other words, one of the effects of using this test is that it hardens states’ protection and assertion of their sovereign independence and territorial integrity.

An un-humanitarian agenda?

But it’s also dangerous for a more specific reason. It points to a choice of enforcement over protection. Enforcement née war seems, at least on the surface, an awfully strange response to the humanitarian crisis engulfing southern Somalia. It is incredibly trite to say that intervention is possible because four women have been kidnapped, rather than because Somalia is suffering through the worst famine in recent history and mass displacement, with warnings that the total number of deaths could reach three-quarters of a million.

Trite, but legal. A depressing corrective for those who believe in international law’s progressive agenda.