The following is the first instalment in a four-part series by Jenna Dolecek on justice and accountability for victims and survivors of atrocities committed in Myanmar. Jenna is an international criminal investigations consultant who investigated crimes committed in Myanmar through her work at Myanmar Witness (Centre for Information Resilience) and the United Nations Independent Investigative Mechanism for Myanmar.

What does it take to turn a dream into reality?

After eight decades, the conflict in Myanmar is now the longest ongoing civil war in the world. In February 2021, Myanmar experienced its second military coup, led by Senior General Min Aung Hlaing. Accountability efforts have largely focused on the Rohingya genocide, which occurred between 2015 and 2019. The only court that has accepted a criminal complaint on Hlaing’s post-coup crimes is Turkiye, while the International Criminal Court (ICC) is unable to investigate these crimes due to a lack of jurisdiction. Very little justice has been delivered for the crimes committed against ethnic groups since the start of the civil war in the 1940s.

Unfortunately, death tolls were not well recorded from the 1940s to 2010, so statistics will not be accurate. The Political Economy Research Institute from Amherst University, cites two estimates for conflict-related deaths from 1946-2006 as 100,000 to 140,000. From 2010 (when the Armed Conflict Location and Event Data Project began monitoring the conflict tin Myanmar) to right before the coup, they estimate over 9,000 civilian deaths. As of December 2025, casualty estimates range from 5,000 to nearly 8,000 deaths since the coup in February 2021. This conflict has very likely cost the lives of well over 150,000 people. As of March 2025, over 3.5 million people have been internally displaced since the coup with another 1.5 million refugees seeking asylum abroad.

It is now well documented that the junta carries out attacks indiscriminately against civilians, which qualify as war crimes. Extensive United Nations investigations, civil society documentation, and verification by open source investigations cover attacks on schools, healthcare, religious centers, and even weddings. Widespread arbitrary detention, torture, and sexual violence all qualify as crimes against humanity. Last but not least, the crime of genocide perpetrated solely against the Rohingya with the most recent campaign spanning 2015-2019.

The Dreaming of Justice series will explore how justice is understood, pursued, and constrained in the context of Myanmar’s ongoing conflict. Across four interconnected blogs, the series traces how different understandings of justice in Myanmar intersect with legal, political, and practical realities of pursuing accountability.

The first blog, What Justice Means to Myanmar’s Communities, looks at how people across Myanmar define justice, from demands for prosecution to calls for respect for human rights, reparations, and recognition. The second blog, Leveraging Universal Jurisdiction for Accountability in Myanmar, analyzes the universal jurisdiction cases filed to date, assessing the progress made, persistent challenges, and what these efforts reveal about the realities of international law. The third installment, Alternative Approaches to Accountability in Myanmar, turns to hybrid courts and community-based models of justice, drawing lessons from the Extraordinary Chambers in the Courts of Cambodia and Rwanda’s gacacacourts. The final installment, Double Standards in Global Support for Ukraine and Myanmar, reflects on the stark contrast between the world’s rapid mobilization for justice in Ukraine and its limited response to Myanmar, reflecting on what these disparities reveal about the global politics of accountability.

Together, these pieces aim to shed light on the many forms justice can take and the enduring struggle to turn a dream into reality for the people of Myanmar.

Part 1: What Justice Means to Myanmar’s Communities

With Myanmar’s conflict ongoing and an authoritarian regime in control of the country, domestic accountability is unlikely to occur anytime soon. Myanmar’s 2008 Constitution gives the junta full judicial control and immunity, thereby preventingany sort of domestic prosecution. With news outlets predicting a junta party win in the current “election”, this will be solidified even further. This poses a massive barrier to justice for victims. The National Unity Government, the shadow government in exile, has dissolved the 2008 Constitution and replaced it with their own. This is an important step for post-conflict nation building and transitional justice, but it has no power as of now.

With international accountability processes often taking years, the real question is, what does accountability look like to the people of Myanmar? This first installment of the series looks at how people across Myanmar define justice, from demands for prosecution to calls for respect for human rights, reparations, and recognition.

Some in Myanmar and those among the diaspora support an international process, including the use of universal jurisdiction. However, many have understandably lost faith in the international legal system altogether. Both perpetrators and victims can die before a judgement is reached and many victims never receive reparations. There have been plenty of successes in international criminal law, but the gears of international justice grind slowly.

In the context of atrocities committed in the former Yugoslavia, Slobodan Milosevic died in custody before a judgement was reached. Still, domestic courts in Bosnia and Herzegovina have continued to try perpetrators for over 30 years. In Cambodia, two defendants, including Pol Pot, died before trial, while another was deemed unfit for trial due to dementia. The Extraordinary Chambers in the Courts of Cambodia are still active and trying cases over 40 years after the genocide by the Khmer Rouge. The amount of time these processes can take, as well as the challenges plaguing international criminal processes can undermine faith in this form of justice. These challenges include internal disputes over criminal responsibility, insufficient evidence, or political pressures which may influence decisions throughout the legal process.

A study by the Centre for Peace and Conflict Studies (CPCS), asked over 1,000 individuals in Kachin, Kayah (Karenni), Kayin (Karen), Shan, and Mon states about their desired post-conflict outcomes. Peace was the main concern, but those interviewed specified their specific desire for a lasting peace. Victims did not just want an end to the hostilities, but a peace that could bring respect for human rights and autonomy. If a peace process were to occur, affected communities want to be informed, consulted, and included. After all, they know what is best for them, as the needs of different states and ethnic groups can vary due to environment, history, culture, lived experience, and so on.

Even if hostilities cease and trials begin, they won’t mean much if human rights continue to be violated and peoples’ lived realities do not improve. Freedom of movement and expression, access to healthcare and education, fairer distribution of wealth generated by natural resource rich regions, and equality/anti-discrimination, were among the most pressing socio-economic needs raised by those interviewed. An end to hostilities is critical as these needs cannot be addressed amid ongoing violence. While Ukraine has seen success with holding trials amid an ongoing conflict, their government is sympathetic to justice, accountability, and the livelihoods of its citizens, and is not an authoritarian junta who are the perpetrators of crimes against their own people. If life does not improve, what difference does it make if perpetrators are on trial?

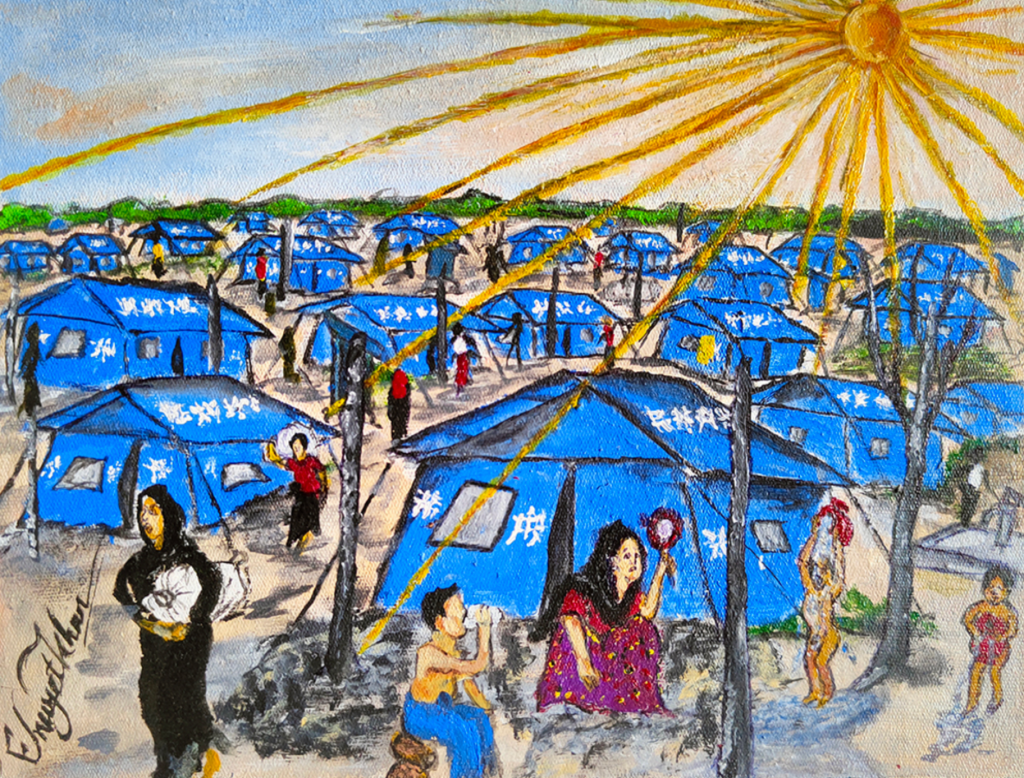

From October to November 2022, researchers from Legal Action Worldwide conducted a survey in Kutupalong camp in Cox’s Bazaar, Bangladesh, where around a million displaced Rohingya people reside. Unsurprisingly, one of the first takeaways was the Rohingya community’s desire for local governance due to over 50 years of state sponsored persecution and genocide. Similar to the ethnic groups surveyed by CPCS, their immediate concern was meeting socio-economic needs and thereby prioritizing the improvement of daily life and securing their protection over holding perpetrators accountable.

The Rohingya people also have their own cultural and religious forms of justice. The Rohingya’s shomaz, or committee of male community leaders, convene both perpetrators and victims and act as mediators and arbitrators who determine punishment or compensation. Coming from a more communal system, the Western adversarial system seems at odds with what they may be used to. One individual even remarked that they do not understand international courts or trials in absentia because, if the victim is dead, how can all parties be present and participate in a fair process?

While respondents stated that retributive justice remains important, it was at the bottom of their list. A graph within the study showed four categories that were ranked as follows, with 1 being the most important and 4 the least: 1) Citizenship & Rights, 2) Compensation, 3) Protection, and 4) Punishment. The ranking offered by participants in the survey is further echoed in a forthcoming report by Knowledge Hub Myanmar, where Rohingya respondents in Rakhine State also prioritized citizenship, rights, protection, and then accountability. Given how difficult it is to survive in Cox’s Bazaar, even before severe humanitarian aid cuts, it is no surprise that easing the challenges of daily life and securing their future are more important objectives. Refugees in Cox’s Bazaar are not allowed to work or travel and therefore depend on aid. The Rohingya community in general is denied citizenship in Myanmar.

When it comes to the 2021 coup and the views of younger generations, many support international accountability mechanisms. Various ethnic and student organizations call for cooperation with international justice mechanisms as well as for the ICC to investigate post-coup crimes. Two women’s rights organizations also support an investigation by the ICC. Unfortunately, the Court lacks jurisdiction. It can only investigate atrocities committed against Rohingya people that have been forced into Bangladesh where the Court enjoys territorial jurisdiction.

It is easy for some communities, perhaps particularly the West, to assume that their own frameworks are best. However, victims should always be the priority, and they may desire alternative approaches. The question must then be asked: who does justice in the “Hague Bubble” actually serve? A United Nations report remarked that people in Myanmar are laying the foundation for future transitional justice initiatives but want “new narratives free of ethnic chauvinism.” The report also noted that any initiatives must be “owned and led by the people of Myanmar.” For those of us in the West who are used to the adversarial and punitive system, courts are the obvious answer. For others, courts may not be an answer at all. For some, they may have a place but are not the only desired solution.

Everyone dreams of justice, but everyone’s dreams look different.Understanding these differing visions is essential before any meaningful path to accountability can take shape. In the next instalment, we examine one of the few legal tools available that attempts to turn these aspirations into tangible action: leveraging universal jurisdiction for accountability.