The following is a guest post by Sarah Nimigan, on the recent travel of Israeli Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu over Canadian airspace, in defiance of the ICC’s warrant against him. Sarah is a an Academic Research Associate with the Centre for Transitional Justice and Post-Conflict Reconstruction, at the Western University, in London, Ontario.

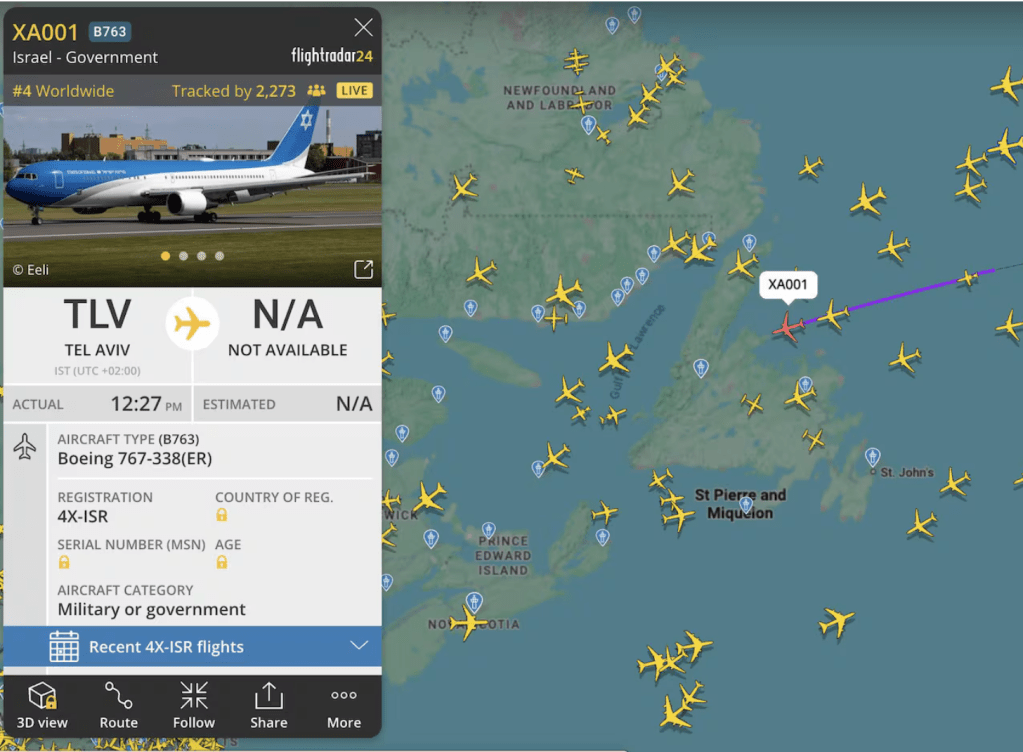

Earlier this month, Israeli Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu flew over three Canadian provinces on his way to Washington D.C: Newfoundland, Prince Edward Island, and New Brunswick. The failure to prevent the use of Canadian airspace and to arrest Netanyahu, led to heavy scrutiny of the Canadian government and Prime Minister Mark Carney. The obligation to arrest the Israeli leader stems from his outstanding arrest warrant by the International Criminal Court (ICC) for allegedly committing the war crimes and crimes against humanity, including starvation as a method of warfare and of intentionally directing an attack against the civilian population, murder, persecution, and other inhumane acts. When he became Canadian Prime Minister, Carney said Canada was prepared to arrest Netanyahu if he visited Canada. What happened?

The point of this post is not to debate the merits of the charges against Netanyahu. They exist and create a cascading series of obligations on the States Parties to the ICC, including Canada. What this post does is examine what would have happened if, instead of allowing Israel to use its airspace, Canada had arrested Netanyahu.

Canada’s relationship with the ICC has historically been a close one. Ottawa took a leading role in its establishment and institutional operationalization within the Court, and has had nationals occupy key roles in both the judiciary and the Office of the Prosecutor at various points since its conception. Canada demonstrated its strong commitment to the Court by not only ratifying the Rome Statute but also implementing it into domestic law, under the Crimes Against Humanity and War Crimes Act.

Continue reading