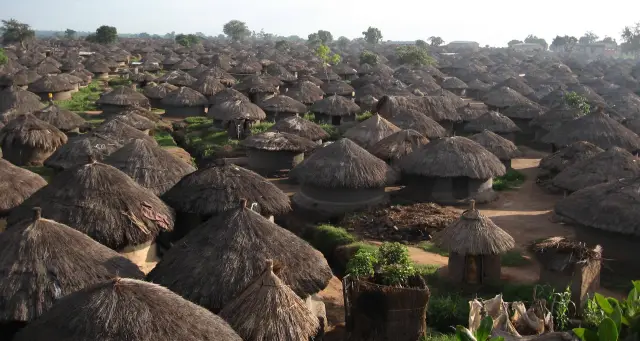

One of the 'protected camps' that were established during the LRA conflict in northern Uganda (Photo: http://joshuadysart.com)

The Lord’s Resistance Army (LRA) conflict effectively ended for northern Uganda in 2006, after 20 years of suffering, when the LRA moved out of Uganda at the start of the Juba Peace Talks. Despite relative peace returning to the area, the multiple legacies of this conflict have still not been fully addressed. One of the most contentious issue is the question of how to deal with human rights violations committed by the Government of Uganda (GoU) and the Uganda People’s Defence Forces (UPDF), as well as its predecessor, the National Resistance Army (NRA). The academic literature on the topic and human rights organisations are pretty clear about the fact that human rights violations were committed, in particular by the NRA in the 80s and 90s. Until this day, northern Ugandan victims call for justice for these crimes while the UPDF claims that it has prosecuted all violations that were committed. The ICC, with its jurisdiction starting in 2002, cannot help in this case, but there are also allegations regularly brought forward in northern Uganda that may fall under the jurisdiction of the ICC and are thus of particular interest.

When the Government of Uganda was not able to beat the LRA militarily, it started to drive the Acholi civilian population into so-called ‘protected camps’ in 1999. Civilians that did not comply were subjected to beatings or random shelling of their villages. In these camps people lived in grievous conditions around UPDF barracks. The army largely failed to protect the civilian population against LRA attacks on the camps. At the same time, diseases like Cholera, Ebola and Aids spread due to lacking hygiene and crowded conditions in the camps. At the height of the conflict 1.8 million people lived in such camps and roughly 1,000 of them were dying each week. Many northern Ugandans – from political and religious leaders to ordinary citizens – have claimed that this UPDF policy amounts to genocide. Only recently, an argument between the retired Bishop of Kitgum Macleod Baker Ochola II and a UN representative ensued at a workshop over whether the camp policy amounts to genocide, as claimed by Bishop Ochola.

Retired Bishop Ochola during the workshop at which he raised the genocide allegations (Photo: Sam Lawino/Daily Monitor)

It is clear that the conditions in the camps were horrendous. Chris Dolan, the Director of the Refugee Law Project in Kampala, Uganda, has fittingly described the camp system as ‘social torture’. According to the UN Office for the Coordination of Humanitarian Affairs the camps violated several rights of the displaced and nearly all UN Guiding Principles on Internal Displacement. Principles violated included, for example, the need to consult the people affected by the displacement (7.3), to minimise the time of displacement (6), to provide basic standards of living and medical care (18, 19), freedom of movement (14), the protection from abuses (11), and the protection of property (21). A diplomat I interviewed compared the IDP camp system to British concentration camp tactics during the Boer Wars in South Africa, and a staff-member of a human rights organisation stated in an interview that the GoU camp policy likely constitutes a crime.

Little doubt remains that the camp policy of the Ugandan Government was inhumane, maybe criminal, but does it amount to crimes under the Rome Statute? The Office of the Prosecutor of the ICC has not made any of the findings from its investigations of alleged UPDF and GoU crimes public, and I am not aware that the legal literature has attempted to clarify this aspect. I would like to give my own assessment of this question in the following paragraphs, stressing that I am not a lawyer and that my analysis might be open to criticism by people more experienced in questions of international criminal law.

The genocide allegations brought forward fall under Article 6 of the Rome Statute. The camp policy might meet Article 6 c stipulation of ‘deliberately inflicting on the group conditions of life calculated to bring about its physical destruction in whole or in part.’ The difficult question, as with all genocide findings, is the mental element of the crime. The prosecution has to prove that the GoU had the intent to destroy part of the Acholi population. From my own analysis of the conflict I would say the camp conditions are better defined as a consequence of the GoU’s indifference towards the north and its unwillingness to fully integrate the region into the economic and social systems of Uganda. President Museveni could not expect votes from the north during the active phases of the conflict anyway, so he didn’t really care what was happening there. I would say the camp policy was a case of neglect, but not the deliberate infliction of conditions of life calculated to destroy the Acholi. This becomes especially clear when comparing the GoU camp policy to the situation in Darfur, where the ICC issued a warrant for genocide. In this case the Government of Sudan deliberately hampered the delivery of humanitarian aid. In Uganda, the contrary is the case. The GoU even actively used international donor agencies to maintain and finance its camp policy and skillfully passed on the bill for the internal displacement it had caused. I won’t completely rule out that intent by the GoU could be proven, but I think an analysis of the conflict implies (criminal?) neglect rather than intent to destroy.

An IDP Camp in the western Sudanese region of Darfur. At first glance the camp situations look similar, but the nuances count for a genocide finding.

In my opinion, charges of crimes against humanity might actually be more interesting in this context than genocide charges. I assume that war crimes do not apply as it is debatable whether the LRA conflict was an international conflict during the time the camp policy was implemented. In fact, the ICC ruled that the Ituri conflict, in which Ugandan and Rwandan troops were meddling, was an internal conflict. So the assumption that the Court would rule in a similar way in the case of Uganda, despite the role of the Government of Sudan and the LRA’s operations in southern Sudan, is probable. The following sections will debate possible charges for crimes against humanity.

Possible counts for crimes against humanity are extermination (Article 7 I b), imprisonment (Article 7 I e), rape (Article 7 I g) and other inhumane acts (Article 7 I k). Extermination in Article 7 b is applied in particular to cases in which food or medicine is withheld from civilians. Current interpretations of international criminal law governing humanitarian situations state that the law demands that authorities have to allow humanitarian access to the displaced persons. Hindering this humanitarian access is a crime, but it is mostly not considered a crime to expose civilians to the risk of hunger, starvation or diseases. Again, the difference between the Darfur and Uganda cases helps to draw the line. In Darfur aid was withheld deliberately, in Uganda it was used to maintain the camp system. Article 7 I b is thus not applicable.

According to commentaries, imprisonment under Article 7 I e has a narrow definition and would thus not include the camp policy. Rape under Article 7 I g has been documented by both human rights organisations and researchers. Yet it remains unclear whether this is a problem of individual soldiers or a systematic and wide-spread government policy, as required under the gravity criterion of the Rome Statute (see § 46). Some of my interview partners claimed that rape was systematic, but there is no clear proof in the literature. A fact that speaks for the gravity of the crimes is that the Pre-Trial Chamber has ruled in § 46 of its first decision on the gravity threshold that the ‘social alarm’ surrounding the allegations should be taken into consideration when determining the gravity of a crime. Since victim demands for justice for GoU crimes are still very widespread today, it is fair to assume that there is ‘social alarm’ in northern Uganda. Apart from the gravity of the crimes, the complementarity issue is not clear, as the UPDF claims it has court martialed all of its soldiers who committed rape. Organisations like Human Rights Watch on the other hand have documented many cases in which soldiers were simply transferred without being held accountable for rapes. Rape charges thus remain a possibility.

Other inhumane acts under Article 7 I k have to be similar in gravity to the other counts in Article 7. Additionally, intent is needed and the acts have to be deliberate. According to the commentary, it covers all acts similar to but short of torture, particularly if they violate human dignity. If the GoU camp policy is defined as social torture, following Chris Dolan, it might be possible to apply Article 7 I k. From the accounts of life in the camps it would be difficult to argue that the conditions are not close to torture and do not violate human dignity. Yet, as with the crime of genocide, it would be difficult to prove that the GoU is deliberately and intentionally creating these adverse conditions in the camps.

To sum up, doubts remain whether the GoU could be charged for crimes under the Rome Statute for its camp policy during the conflict. Charges for rape and other inhumane acts may have a legal foundation. The mere possibility that allegations brought forward by many living in the formerly war-affected areas of northern Uganda could be relevant in the ambit of the Rome Statute calls for a clear statement by the ICC Office of the Prosecutor (OTP) in which the investigations conducted so far are described in detail. Despite the importance of publishing additional information the OTP has consistently declined to reveal any details about its investigations of GoU crimes. On an interesting side note, Ugandan President Yoweri Museveni himself was quoted by the New Vision government newspaper on 13 March 2010 stating that he would be ready to face a trial at the ICC if he was found to have committed crimes against humanity.

Patrick, I have always appreciated your effort to bring out the Konny crisis to the world. I am a Ugandan who once visited one of these camps in Gulu. It is true that the conditions in these camps were horrendous though the Government aimed at protecting these innocent civilians and to easily draw a distinction between the LRA rebels and the civilians. However, these camps were not hygienically maintained but the fact remain that they were set up by the GoU for a good cause.

Reblogged this on Patricia Alejandro and commented:

The gravity criterion of the International Criminal Court (ICC) (Rome Statute § 46) is an interesting principle: crimes must meet a certain standard, such as crimes against humanity and war crimes, and must be widespread and systematic government policy. This means that UPDF crimes in northern Uganda will go unaddressed at an international level, unless the ICC determines that both requirements are met.

For the rebuilding of the rule of law, ending the culture of impunity, in Uganda, these crimes will have to be addressed somehow, somewhere. If not at domestic courts, then where? While the ICC makes the valid argument that it must apply the law equally to all (its definition of an impartial Court), what happens to those crimes that will never be brought to court?

Pingback: Weekend Reading « Backslash Scott Thoughts

Pingback: Weekend Reading « Backslash Scott Thoughts

Pingback: Thoughts on Invisible Children and WikiLeaks « Backslash Scott Thoughts

Patrick,

Thank you for your article.

How can you say that the conditions in the camps were a “consequence of GoU indifference to the Acholi people”? What consequence are you implying? Are you justifying for crimes that were committed by Museveni’s on the Acholi people? In a democratic society, people votes for whoever they likes and want to be their leader, there is no justification under national or international law to be subjected to such abuse because you are not voting for a particular person or people.

If anything can be said, genocide in Acholi is very easy to prove just as genocide in Rwanda and Darfur. Academics, Western Medias and NGOs have reported the same thing that they were told by the Museveni’s PR and repeated it again and again. This is getting to sink in to the detrimental of the Acholi people. Often the analysis of the Acholi problems is seen from the eyes of the Western, NGOs (who may be complicit to the genocide against the Acholi people) and not from the Acholi people who do not have a voice and their voices are heard from few who are bribed by the GoU or work with the GoU.

The Museveni’s camps which were set up in Acholi does not falls within the definition of internally Displaced Persons camps. These were Concentration Camps which Museveni himself masterminded in 1986 to commit genocide on the Acholi people, as for element of intention to commit genocide it has already been proven

Click to access m7.subject_-_rethink_scan1.pdf

The camps were not there to protect the people but it was an easy access for Museveni’s army to have access to people they want and many were torture, forced disappearance, arbitrary arrest, the policy of rape anything that moves, curfew were imposed (11am – 3pm) anyone found outside within these times were labelled LRA and the policy was shoot to kill.

We have evidence of Museveni having a rebel group known as Kardusta, who had to pretend to be the LRA and 95% of atrocities were committed by the NRA/UPDF i.e. 98 people burnt alive in Acholibur. Some soldiers who were present on the night had already confessed that these were NRA/UPDF soldiers.

The soldier in this story was deployed in Northern Uganda immediately after Museveni came into power and the same soldier talk of atrocities which were committed in Rwanda by RPF

http://www.inyenyerinews.org/human-rights/kagames-unreported-killings/

To understand the Northern Uganda genocide, you have to start with Rwanda and connect the dot to the crimes committed on the Acholi people with that in Rwanda.

I will not to go into the ICC Articles; you concentrated primarily on Article 7 and not analysis of Article 6

Pingback: Addressing injustice and managing expectations: Displacement and transitional justice discourses in Northern Uganda | TerraNullius

Pingback: One Year After Kony2012: Resources for the Lord’s Resistance Army | Backslash Scott Thoughts

Pingback: Tell Me More About the Genocide & Acholi Quarters | Ande in Acholi

Pingback: Ongwen’s Indictment and Lukodi | Backslash Scott Thoughts

Pingback: Internally displaced women social rupture and political voice - Real Media - The News You Don't See

Acholi want independent inquiry to the genocide in Acholi Land. the previous inquiry was full of lies and based on report cooked by Mr Museveni’s Right wing so call invisible children. We also want Ongwen case to be review as the killing in Northern Uganda was not only done by LRA alone but UPDF ALSO were the key players up to now.

Pingback: Blog: Great Lakes King of dictators | The Hague Peace Projects