The following guest post was written by Dan Plesch, Professor of Diplomacy and Strategy at SOAS University of London and a Door Tenant at the Chambers of Stephen Kay KC at 9 Bedford Row. His books include, ‘Human Rights After Hitler’, ‘America Hitler and the UN’, and ‘The Beauty Queen’s Guide to World Peace’. His work on the modern relevance of the United Nations War Crimes Commission has featured in the Associated Press, the US National Public Radio, Amazon’s acclaimed documentary ‘Getting Away with Murder(s)’ and Netflix’s 9th episode of the ‘Greatest Events of WW2’.

As a Head of State, Adolf Hitler was indicted for war crimes by several European states in the winter of 1944-45 under their domestic laws as well as international law. The three states, Belgium, Czechoslovakia and Poland were supported by a dozen others, including China, France, the UK and the USA who were all members of the United Nations War Crimes Commission. The legal documents were sealed for decades. When they were finally released in in the 2010s, their significance warranted a news story by the Associated Press in 2017, The documents were not available to the International Court of Justice as it considered the arrest warrant case over a decade earlier.

At a time when many are discussing and debating head of state immunity, the Hitler indictments point the way to further reducing the impunity of national leaders in the twenty first century.

As a historian observing and engaging with the community of International Criminal Law, I find it curious that this state practice has been given no weight by generations of judges, lawyers and scholars. The unanimous view of sixteen leading states that Hitler was personally and functionally liable for the atrocities committed in his name confounds the established view that individual states cannot legally prosecuted the sitting Heads of State of other governments.

The criminal liability of Heads of State and of Government, as well as Foreign Ministers is a live issue once more with the Paris Court of Appeal’s ruling that French investigating judges could issue an arrest warrant against Syrian President Assad and with the complaints before the Office of the Swiss Attorney General against Israeli President Herzog. For some commentators, these actions contravene the 2002 decision of the International Court of Justice (ICJ) in the Arrest Warrant case, in which the ICJ held that customary international law includes the rule that sitting Heads of State, Heads of Government, and foreign ministers are immune from criminal jurisdiction, including arrest warrants and indictments, by foreign national courts, including for war crimes and crimes against humanity. The ICJ distinguished personal immunity from functional immunity, and distinguished national criminal jurisdiction from international criminal jurisdiction such as the International Criminal Court (ICC)

The long overlooked customary state practice from the 1940s can be seen as contradicting the ICJ judgment and so reinforcing the validity of the Assad and the Herzog cases. The now unsealed documentary record in relation to efforts to prosecute Hitler provides individual and multilateral state practice from the 1940s that set the immunities of Heads of State and Government in a decision of the United Nations War Crimes Commission (UNWCC) and subsequent actions of that body and its members states. Thus, the ICJ overlooked the most important state practice precedent relevant to its inquiry – and in fact the only time prior to 2002 that the world’s most powerful states considered the issue together.

At a time when many are discussing and debating head of state immunity, the Hitler indictments point the way to further reducing the impunity of national leaders in the twenty first century. More details on these UNWCC-supported charges are now available in recent research into the unsealed archives of this multinational organisation of the mid-1940s. It has been presented in London and The Hague. The International Law Commission has recently received submissions to be considered in its work on the Immunity of State officials from foreign criminal jurisdiction.

In this post, I am presenting the UNWCC and member states practice on the issue, building on my 2017 work, ‘Human Rights After Hitler’, which established that “Hitler was an indicted war criminal at death.”

The UNWCC was constituted by sixteen states in 1943 in London and accorded formal diplomatic status by the British government. It records relevant to the immunities issue include legal submissions by member states, Commission minutes and papers, correspondence between the Commission and Member States, and the Peace Treaty between Italy and the Allies in 1947.

In 1944, the UNWCC adopted the rule “discarding as irrelevant the doctrines of immunities of heads of State and members of Government, and acts of State” when providing an advisory opinion that individual states could prosecute Hitler and that therefore the Commission could list him as an accused war criminal subject to arrest by Allied forces. The decision, described in the Commission’s History, was published by the British government in 1948, but has been given scant attention since. This UNWCC decision was made by the sixteen member states after investigations by a sub-Committee led by Lord Wright of Durley, a former senior English judge. The Commission itself was chaired by Sir Cecil Hurst, a member and former President of the Permanent International Court.

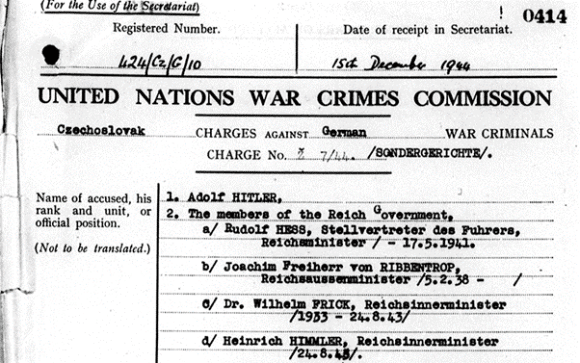

This decision of “discarding as irrelevant” Heads of State immunities constitutes significant evidence of customary international law consisting of the advisory opinion of the UNWCC and the opinio juris of its member states and of the judges and experts that represented them. Hitler and his senior officials were then indicted by Czechoslovakia, Poland and Belgium. The Commission considered and approved the charges as meeting a prima facie standard. The UNWCC then listed Hitler and his officials as accused war criminals subject to arrest for trial in the domestic courts of the indicting state.

At this point, in the winter of 1944-45, the UNWCC was the only institutionalised international legal response to Nazi crimes, as envisaged by the 1923 St James’s declaration and the 1943 Moscow statement on atrocities. The effort that led to the London Charter for the International Military Tribunal at Nuremberg was not yet even an intergovernmental negotiating process. That Hitler died and his Foreign Minister Von Rippentrop was condemned at Nuremburg does not negate the authority of these indictments holding the individuals liable for crimes while they were still in office.

In addition, Gauleiters (Nazi-imposed heads of government of nation states and provinces incorporated into the Reich) were indicted while still in office and later convicted in domestic courts across continental Europe during the period. Prosecutions of Gauleiters endorsed by the UNWCC were made by Czechoslovakia, France, Luxembourg, Norway, Poland and Yugoslavia. All of these states convicted their former Nazi rulers when they were no longer in office but were still regarded as personally liable for their actions as heads of government in particular territories. Some may argue that these men were not Heads of State, at the time that was widely recognised as their role.

Then in 1947, pursuant to the peace treaty between the Allies and Italy, Ethiopia had ten cases against Italian leaders endorsed by the Commission. The peace treaty does not include immunities, not even for Marshal Badoglio, despite the fact that he brokered Italy’s change of side in the war and had then briefly been its Prime Minister.

Article 45 of the peace treaty required Italy to apprehend and surrender for trial “Persons accused of having committed, ordered or abetted war crimes and crimes against peace or humanity”. The accused included Marshal Badoglio and General Graziani both of whom had been heads of the Italian government of Ethiopia. Charges ranged from the use of poison gas to cultural crimes.

The peace treaty was signed by all the states that had been at war with Italy, including four members of the newly created UN Security Council. The absence of any provision for immunities and the subsequent international support through the UNWCC for the indictments of two of the heads of government of Ethiopia can be considered as a body of personal customary international criminal liability of former heads of government in keeping with the trials of the former Gauleiters.

The Indictment documents of Hitler along with his high and other officials are provided here. The Commission endorsed indictments against Hitler submitted by Belgium, Czechoslovakia and Poland as having met a prima facie standard for prosecution. The Commission required states to cite both the crimes under domestic and international law. The Commission considered and determined what constituted International Criminal Law in the 1940s and provided the advisory opinion that this included the Hague Conventions and the “Versailles list” prepared by the Commission on Responsibilities in 1919. Often overlooked today, the “Versailles List” was given significant status because Japan had been amongst the allied powers that drew up the list and then it had been accepted by Germany.

The Czech indictments of Hitler alone cover 11 separate cases amounting to over 600 pages of evidence. Two indictments concerned the illegality of Nazi “courts” as not meeting any minimum standards of justice and not being legal to establish in occupied territory. A rather technical issue on which to indict a Head of State and of Government. Other Czech charges included mass exterminations of Jews, exterminations of villagers close to resistance actions at Lidice, and lists of named individuals. Now familiar names such as Buchenwald and Dachau are the focus of some indictments.

Poland’s focus was the “biological extermination of the Jews in Poland” in violation of the 4th Hague Convention of 1907 and war crimes decrees made by the exiled Polish government in London in 1943. Belgium followed suit with charges concerning Auschwitz and Buchenwald. Belgium also developed charges concerning the murder of prisoners and pillage against Hitler.

The UNWCC-related cases presented here warrant consideration not just by the International Law Commission (ILC) but also of the ICJ. It is curious that the ICJ was not aware of the work of the President of the interwar Permanent Court in leading the UNWCC to set aside considerations of immunity of national leaders given that it had been published officially in 1948. It would be odder still if, now that the original documents are fully available, the ILC and the ICJ did not consider the UNWCC-related cases in their future work.

It may be that states and other interested parties take up this newfound evidence overturning the notion of absolute functional and personal immunity of Heads of State. Of course, there are risks of spoiling and frivolous use of the restoration of Head of State criminal liability. But such concerns cannot simply obliterate the cases from the 1940s. If greater legitimacy is sought for bi-lateral indictments, then forms of hybrid pre-trial process – the UNWCC model – and hybrid courts are available.

One needs to ask why this material was set aside for so long. It is not merely a question of poor research and a failure to challenge an established consensus. The US led a process permitting the Getting Away with Murder(s) with the excuse of rebuilding Germany, as is well documented by now. It may well be that those interested in holding Presidents Assad, Hertzog and Putin to account for their disparate alleged crimes will find this material of specific use.

Pingback: An Important Past: Since Hitler, Heads of State have No Immunity – United Nations War Crimes Commission archive