The following introductory post was written by Mark Drumbl and Barbora Holá, authors of the book Informers Up Close, the subject of JiC’s ongoing symposium. For all other contributions, please see here.

You can’t hide your lyin’ eyes

And your smile is a thin disguise

[…]

She wonders how it ever got this crazy

She thinks of a boy she knew in school

Did she get tired or did she just get lazy?

She’s so far gone, she feels just like a fool

My, oh my, you sure know how to arrange things

You set it up so well, so carefully

[…]

You can’t hide your lyin’ eyes

And your smile is a thin disguise

– The Eagles, ‘Lyin’ Eyes’, 1975, from the album ‘One of These Nights’

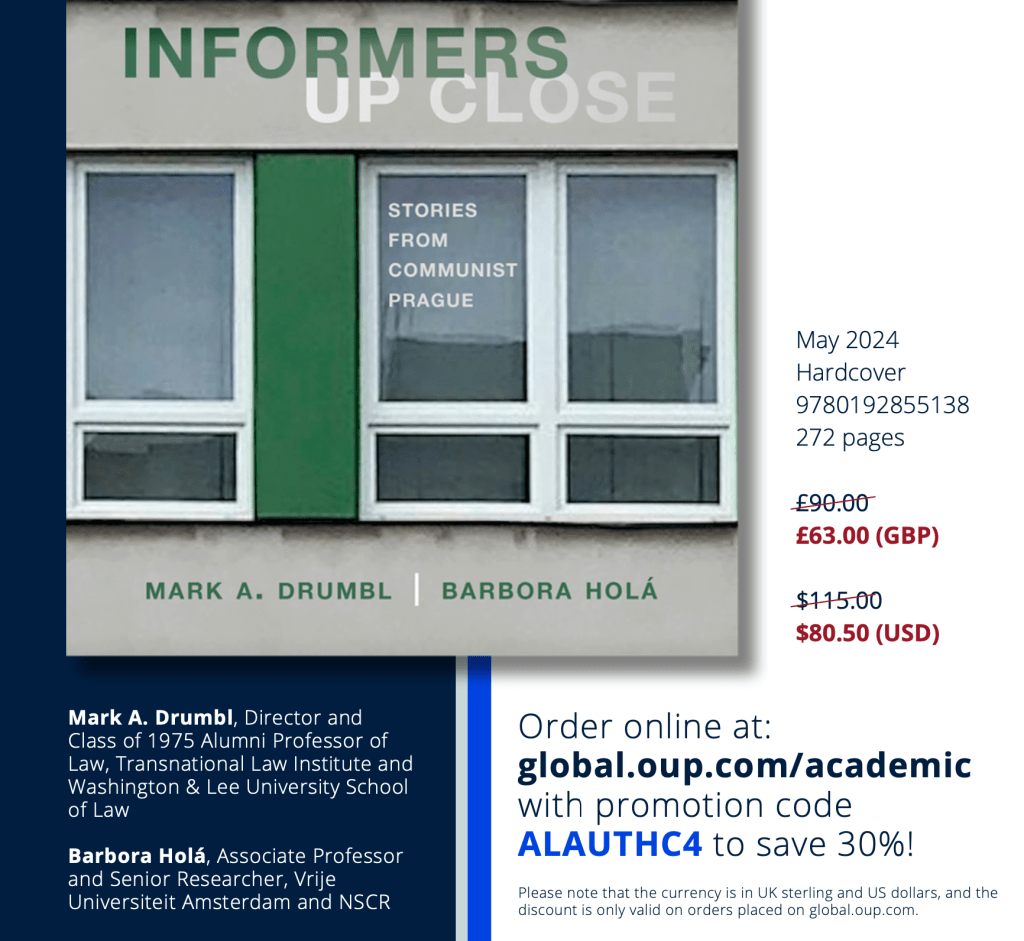

Our new book, Informers Up Close, explores two questions: (i) why ordinary people inform on others in repressive times, and (ii) how, after those times end, law and politics should speak of, to, and about informers.

As to the first question — the why — our case-study is Communist Czechoslovakia (1948-1989) and its secret police, the Státní bezpečnost (StB). Our focus is on ‘everyday informing’. We construct Czechoslovak state-society relations as interactively webbed and as illustrating both participatory dictatorship and social engineering. The source-data we mostly rely upon are the StB secret collaborator (informer) files. These currently are archived and accessible to the public. We prepared detailed (and biopic) ‘high-resolution’ file-stories. Six are directly included in the book, another seventeen are referenced in the book and are fully accessible on this companion website.

We examine the role of emotions as catalyzing and then sustaining decisions to inform on others. Four emotions in particular jump out in our research: fear, resentment, desire, and devotion. Informing in Communist Czechoslovakia blurred the line between the political and the personal. File-stories showcase an idiosyncratic cocktail of drivers that pulled informers towards and pushed informers away from the StB and vivifies how these sentiments changed and morphed over time. Concepts such as intimacy, power, social navigation, strategy, tactics, and exchange contour the relationship between StB officers and ‘their’ informers. Some informers inflicted great harm on others while also suffering considerable pain. They thereby occupy liminal spaces between victims and victimizers. Many informers were blackmailed into informing, but many turned to the StB to leverage their private wants and actualize their immediate needs.

Pivoting to the second question — namely, the how — our book offers normative takeaways for transitional justice in the Czech Republic and beyond. Following the 1989 Velvet Revolution which ended Communist rule, informers were officially cast as dangers to the nascent liberal democracy. They were unilaterally and collectively excluded from public offices. We find this scapegoating unjustified in light of what had actually motivated informers, which rarely was devotion to the ideology and the regime, and reductive in light of the broad net of complicity among the general public which enabled the Communists to govern for forty years. Pointing an accusatory finger at informers, however, provided a sense of comfort that soothed many Czechs, including those otherwise entwined in Communist governance. We interrogate this comfort and unpack its problematic aspects. In so doing, we demonstrate how, as in other transitional contexts, the new Czech state used transitional justice to serve its political ends. We also explore cruelties that inhere in opening the StB files to the public in a largely unadulterated fashion. Encouraging goals of rehabilitation, reconciliation, and reintegration in the case of everyday informers—rather than ostracism, retributivism, and rejection—we propose a heuristic to guide transitional justice mechanisms in how to approach informers generally.

We propose the following six elements, in no particular order nor weight, as probative in the intersection of informers with transitional justice processes: (1) the degree of harm occasioned by the informing; (2) the constraint to which the informer was subject; (3) the length of time the informing lasted; (4) the motivation of the informer; (5) the content of the conversation, namely whether the informer was terse or loquacious and forthcoming or dissembling; and (6) was the informer aware they are speaking to StB. We emphasize an individualized and fine-grained approach to informers. This framework aims to promote dignity, recognize injury, provide etiological and historical accuracy (particularly as to informer motivations), and render transitional justice more reconciliatory and perhaps even transformative.

This book is rooted in one case-study. That said, it also identifies broader commonalities about the practice of informing within other repressive societies and also within supposedly ‘liberal democratic’ societies. All states, after all, need informers to maintain order. All social movements – whether virtuous or vile – hunger for informers to advance their goals, ferret out dissent, and ultimately prevail. The line between the contemptible snitch and the commendable whistle-blower is indeed very thin.

Informing involves duplicity. It serves as a social practice to make ends meet. It is about silence, omission, outright lying, and shame. It is often about people really hurting each other and also becoming hurt. Informing tears trust. It ruptures the social fabric. Informers understandably provoke strong reactions. We however hope to advance the conversation from reflexive visceral disdain towards a more reflective assessment of how, as The Eagles put it, ‘it ever got this crazy’ such that people everywhere got ‘so far gone’ to be snooping-so-much on each other. How does it happen, like in the Theodor Aman painting, that some people’s lives become documented in such detail through obscured informers, in disguise, that lurk right next to them, so close, standing and then stranding, a dance-askance, so bright yet so shady?

Some informers fade into and blur with the structures of the state, while their targets beside whom they purr remain naked and exposed. Some informed-upons may suspect the ‘set up, so well, so carefully’ and catch the glint of the lyin’ eyes. But many others remain oblivious until the state crumbles. Informers fool others, but then become fools as times change. And many informers themselves are targeted as informed-upons in a web of deceit motored by getting even and getting ahead. The walls, as in the painting, are full of the eyes and ears of on-lookers and to-listeners. A panopticon emerges.

We gazed at Aman’s ‘Ball in the studio of the artist’ in Bucharest, Romania, in September 2024. The following day we did a launch of Informers Up Close at the European Society for Criminology Annual Conference. Romania’s Securitate, much like the Czechoslovak StB and the East German Stasi, followed similar surveillance models. Aman painted well before these times. But here, too, the ubiquity of secrecy emerges, the shroud, the reality than ‘live’ is ‘evil’ spelled backwards, and that both of these words have a companion anagram in ‘veil’. And, in this vein, collaboration, spying, furtiveness, shiftiness, betrayal, and secrets are intrinsic to the human condition.

Transitional justice would do well to better reckon with these behavioral patterns and engage with their complexity. We hope to take one small step in this direction with our book. On this note, we are delighted that such a stellar array of commentators – Cynthia Horne, Novak Vučo, Vladimir Petrović, Kiyala Jean Chrysostome, Emma Breeze, Irit Dekel, and Patryk Labuda – now join us. They take our hands on this journey. We thank Mark Kersten and Aleja Espinosa for kindling and curating it all.