The following contribution by Bart Nauta is part of JiC’s ongoing symposium on Alette Smeulers’ new book “Perpetrators of Mass Atrocities Terribly and Terrifyingly Normal?”. Bart is a historian and interdisciplinary researcher at ARQ National Psychotrauma Centre and a PhD candidate at Utrecht University, where his research explores the concept of perpetrator trauma. You can find all of the other contributors, here.

Attempting to comprehend the lived experiences of perpetrators, in a world fraught with everyday atrocities, is a moral imperative not just for scholars, but for anyone concerned with the present state of the world. Alette Smeulers’ Perpetrators of Mass Atrocities: Terribly and Terrifyingly Normal? invites us to examine without prejudice the unimaginable acts of violence that have been committed by thousands of perpetrators. The book explores the various types of individuals involved in such crimes, offering a rigorously documented resource for scholars, students, and the public.

As unsettling as it may seem, stepping into the minds and moral worlds of perpetrators reveals a disquieting truth: they, too, can be traumatized by their own acts of violence. Their acts of killing or torturing unarmed civilians can develop into a trauma, a psychological wound. Their trauma manifests itself through nightmares and overwhelming feelings of guilt.

The study of ‘perpetrator trauma’ remains in its infancy, largely due to the immense challenges of empirical research, since engaging directly with perpetrators is a daunting task. Fortunately, Terribly and Terrifyingly Normal? provides several meticulously documented case-studies. In doing so, it sheds light on a possibly emerging typology: the Traumatized Perpetrator. What insights on perpetrator trauma can we gain from Smeulers’ work?

We might consider perpetrator trauma a perverse topic, since many would conceive trauma as the experience of victims who must receive recognition, attention and respect. However, Berkeley law professor Saira Mohamed stated that perpetrator trauma ‘recognizes trauma as a neutral, human trait, divorced from morality, and not incompatible with choice and agency.’

Acknowledging the suffering of perpetrators might facilitate greater recognition of the ordinariness of perpetrators of mass atrocity crimes. Generally, people are expected to see monsters in a courtroom’s dock. Acknowledging their trauma shows they are real people who have done terrible things. They are men, not monsters.

Throughout Smeulers’ book, trauma emerges as a recurring theme in the lives of perpetrators—sometimes present before their crimes, during the violence, or in the aftermath, particularly within judicial proceedings. Even before engaging in violence, trauma can be a driving force behind radicalization. Many young individuals who eventually commit acts of terrorism for example, have endured difficult childhoods, and histories of trauma, abuse or hardship, often exacerbated by war and displacement. For instance, the devastation of Chechnya following the Russian invasion left many young men and women vulnerable and therefore more susceptible to extremist ideologies (Smeulers, p.205).

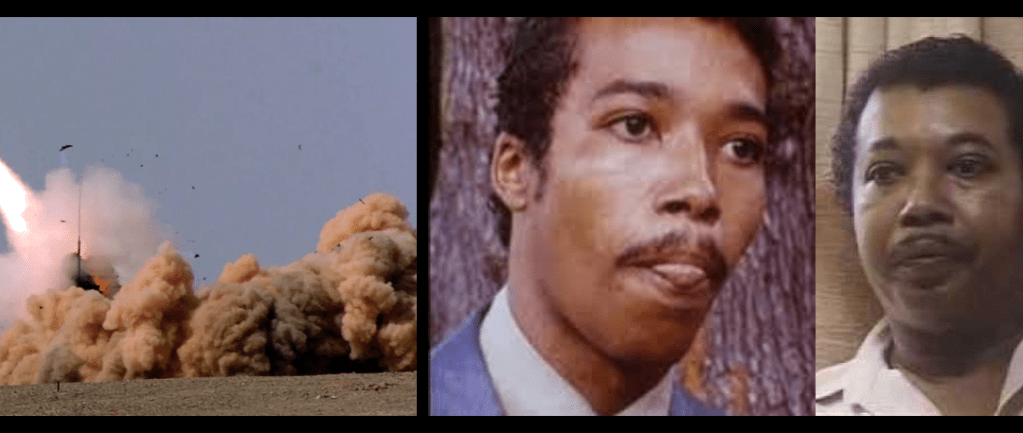

With a remarkable collection of case-studies, ranging from Argentina to Vietnam, Smeulers (p.304) shows how the subsequent act of killing can be traumatizing for some perpetrators. We encounter the self-disgust that South African police officer John Deegan felt after he executed somebody in a fit of rage: ‘I was filled with … self-loathing and disgust at myself and this feeling inside of me that I was a murderer. I actually murdered somebody. I felt very bad about that and I just wanted to run away.’ He was not able to forgive himself, suffered from post-traumatic stress disorder, depression and suicidal thoughts. Other perpetrators, too suffered from trauma after their perpetration. They were haunted by nightmares, overwhelmed with shame and guilt, and contemplated suicide. This was the case of Varnado Simpson, an American soldier who participated in the massacre of My Lai in Vietnam (1968).

Smeulers introduces another form of trauma affecting some perpetrators: the social trauma inflicted by the judicial process. A compelling example is the case of Biljana Plavšić, a convicted war criminal and fanatic for the ethnonationalist Serbian cause. In prison, she expressed resentment towards her fellow inmates, lamenting that they “had never read a single book”, protesting the indignity of being treated as their equal. She experienced her time in prison as traumatic. The experience of a former university professor and politician downgraded to the status of an inmate, can be interpreted as a severe loss of social status.

Humans are social beings, who at all costs try to prevent social exclusion and social defeat. Therefore, we can hypothesize that conviction and imprisonment, as forms of social humiliation, exclusion and defeat, are highly stressful and potentially traumatizing events. This social trauma can be exacerbated by the fact that convicted perpetrators are branded as criminals against humanity. Effectively they are cast beyond the confines of human society.

While we probably shrug shoulders when reading about the laments and egocentric visions of a convicted war criminal such as Plavšić, we must take such examples seriously. Whether we see such testimonies as victimized narratives in order to gain sympathy, or genuine subjective realities of convicted perpetrators, such trauma could hinder reconciliation efforts after release from prison. Traumatized perpetrators, whatever the trauma constitutes, are more likely to be only concerned with themselves, and to blame victims, which can result in heightened intercommunity tensions between victim- and perpetrator groups, and even renewed violent conflict.

Moreover, research indicates that trauma among former soldiers is closely linked to domestic and community violence in crisis regions. This means that many perpetrators, having served as soldiers or members of other violent groups, are at heightened risk of engaging in household violence, perpetuating cycles of trauma, and contributing to further radicalization and future conflict.

The reality of the ‘Traumatized Perpetrator’ means that, alongside supporting victims, we must also consider efforts to facilitate the psychological rehabilitation and reintegration of former perpetrators. All in all, in her book Smeulers has demonstrated why we should take the entanglement of trauma and perpetrators highly serious, because peace within families and between communities depends on it.