Victor Peskin joins JiC for this guest post on the upcoming United Nations General Assembly. Victor is an Associate Professor in the School of Politics & Global Studies at Arizona State University and a Senior Research Fellow at the UC Berkeley Human Rights Center, University of California, Berkeley.

Next week, state representatives from around the world will mark the 80th anniversary of the United Nations Charter during the annual meeting of the UN General Assembly. The conclave of global leaders will also make headlines for (at least) two other reasons. The event marks the first time a head of state facing an international arrest warrant for atrocity crimes takes the podium in the General Assembly Hall. The September meeting also present the first time the United States has denied another head of state—and that state’s entire travelling diplomatic delegation—the right, under the UN Headquarters Agreement, to ascend the same podium by refusing to issue visas to travel to New York.

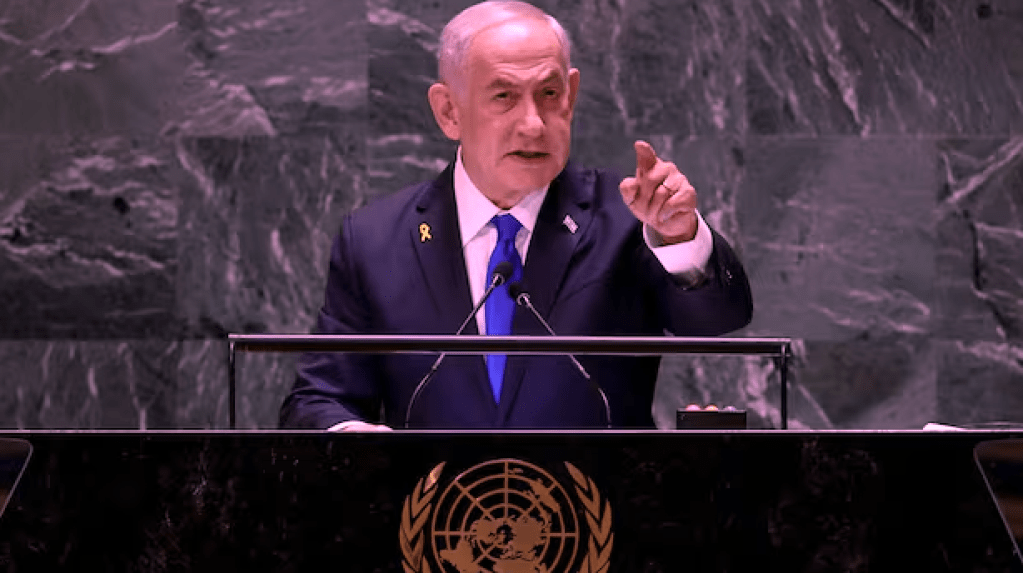

Therein lies an unprecedented forthcoming split screen moment. Israeli Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu—who faces an International Criminal Court arrest warrant on charges of committing war crimes and crimes against humanity in the ongoing Gaza war—will make use of the international megaphone granted to all heads of state during the annual General Assembly gathering. But his political adversary, Mahmoud Abbas, the moderate Palestinian Authority president in charge of administrating parts of the West Bank—and who had long pushed for an ICC investigation of the Israeli leader—will remain stuck back home in Ramallah, relegated to addressing the UN by Zoom.

The 27-member states of the European Union have called on the U.S. to rescind its decision barring Abbas and some 80 other Palestinian officials from visiting UN headquarters. French President Emmanuel Macron—who is poised, along with Canada, Australia, and Britain, to recognize Palestinian statehood at a 22 September conference about a two-state solution—has denounced the Trump administration’s efforts to bar Abbas’ entry to the U.S. as “unacceptable.”Meanwhile, Abbas has launched a diplomatic blitz in the hopes U.S. Secretary of State Marco Rubio will reverse the visa ban. It remains possible that the one-day conference and the General Assembly meeting itself could be moved to Geneva, as occurred in 1988 after the U.S. denied a visa to Palestinian Liberation Organization Chairman Yasser Arafat. Switching the venue might be more likely if, as The Guardian speculates, the Trump administration also uses anti-terrorist laws to bar representatives from Iran, Sudan, Brazil, and Zimbabwe from travelling to New York.

The State Department argues that barring Abbas and his delegation is warranted due to the Palestinian Authority’s failure to condemn Hamas terrorism and otherwise “not complying with their commitments, and for undermining the prospects of peace.” More specifically, Washington seeks to use the visa issue as leverage. This is demonstrated by the Trump administration’s calls for Abbas to terminate: the Palestinian Authority’s appeals to the ICC in the Palestine situation; its support for South Africa’s genocide case against Israel at the International Court of Justice; and its lobbying of other countries to recognize Palestinian statehood.

UN Headquarters as “a sanctuary in the service of peace”

The 1947 UN Headquarters Agreement—which requires the U.S. to promptly grant visas for all visiting heads of state and other state representatives—enshrined the UN citadel, in the view of current French Foreign Minister Jean-Noel Barrot, as“a sanctuary in the service of peace.” Yet, this same agreement has, every September, also rendered UN headquarters a zone of impunity featuring “a rogue’s gallery of dictators,” ranging from Uganda’s Idi Amin, to Libya’s Moammar Quaddaffi, to Egypt’s Abdel Fattah el-Sisi. In the present international criminal justice era, the world body is now poised to become a sanctuary for visiting war crimes suspects, with Israel’s Netanyahu set to become the first to travel to UN headquarters.

Witnessing the ICC-indicted Netanyahu address the UN in-person while his political adversary, Abbas, is denied the same coveted international stage will constitute a new type of international political spectacle. The situation will also invert the presumption of the pariah status of leaders facing international criminal charges for their alleged role in some of the worst crimes known to humanity. With the post-Cold War emergence of international criminal tribunals in the 1990s, human rights advocates predicted that indictments would marginalize targeted leaders while rendering them fearful of arrest if they dared travel abroad. Serbian President Slobodan Milosevic—the first contemporary head of state who faced atrocity crime charges when indicted by the UN International Criminal Tribunal for the Former Yugoslavia during the Kosovo war in 1999—never left his borders. But not so for the three sitting political leaders indicted by the ICC—Netanyahu, Russian President Vladimir Putin, and Sudanese President Omar al-Bashir (in 2019, Sudanese military leaders deposed Bashir and subsequently arrested him, but have not turned him over to the ICC).

The ICC’s Enforcement Problem and the U.S. Visits of Netanyahu and Putin

Bereft of any enforcement powers of their own, ad hoc international criminal tribunals like the ICTY as well as the permanent ICC rely on states to make arrests. All UN member states had a legal obligation to cooperate with the ICTY as well as with its sister tribunal, the International Criminal Tribunal for Rwanda. But the arrest challenge is considerably more difficult for the ICC because only the court’s 125 members are legally required to arrest fugitives. Conversely, it should be perilous for ICC-indicted suspects to travel to ICC member states. Yet, that was not the case for Bashir, who reveled in his status as the peripatetic fugitive, visiting South Africa, Kenya, and a number of other African ICC member states who promised him safe passage. The Sudanese president also travelled extensively to non-ICC member states within and beyond Africa, though he never stepped foot in the U.S. or in any Western ICC member state for fear of arrest. Netanyahu and Putin have each traveled to one ICC member state. In April, Netanyahu travelled to Budapest to visit his right-wing ally, Hungarian Prime Minister Viktor Orban. In September 2024, Putin visited Mongolia.

In recent months, President Donald Trump has welcomed Netanyahu and Putin to the U.S. with open arms. Netanyahu has visited the White House three times since an ICC pre-trial chamber, in November 2024, issued an arrest warrant charging the Israeli prime minister (and his former Defense Minister Yoav Gallant) with starvation as a war crime as well as crimes against humanity in regard to alleged persecution, murder, and other inhumane acts.” The ICC’s warrant for Putin, issued in March 2023, accuses him (and his Commissioner for Children’s Rights, Maria Alekseyevna Lvova-Belova) of committing the war crime of deporting Ukrainian children to Russian territory. Whereas Netanyahu has enjoyed multiple photo ops alongside the American president in the newly gilded Oval Office, Trump embraced the indicted Putin with even greater fanfare, rolling out the red carpet for the Russian leader upon his arrival last month in Anchorage, Alaska, for a one-day summit to discuss the fate of Ukraine.

Given the regal treatment given to Putin, Trump’s on-and-off again friend, it is clear that for the U.S., the act of welcoming heads of state-cum indicted war crimes suspects is not limited to stalwart allies. Analysts heeded the extraordinary spectacle in Alaska where an American president effusively welcomed a foreign leader who not only is under U.S. sanctions for launching the full-scale invasion of Ukraine but also faces a warrant of arrest for war crimes.

Trump, like President Joe Biden before him, has condemned the Netanyahu arrest warrant, insisting the ICC has no right to claim jurisdiction over nationals of non-member states like Israel and the U.S. While Biden lauded the ICC charges against Putin—although Russia too is a non-ICC member state—Trump has not come to Putin’s defense, at least not in the context of the ICC charges against the Russian leader. Still, the image of Trump and Putin together in Anchorage, “preserved for posterity,” in the view of the New York Times, Putin’s “admission back into the fold.” It also appears to have diluted some of the stigma of the ICC’s war crimes charges against the Russian president. Whether the destination is Anchorage, Washington, New York, Budapest, Cape Town, or Nairobi, the repeated visits of indicted leaders, to ICC member states and non-member states alike, serves to further normalize a practice that would have been considered an extraordinary moral breach when The Hague-based court began its work in back in 2002.

The UN Headquarters Agreement and the Politics of Bashir Thwarted 2013 Visit and Netanyahu’s Upcoming 2025 Visit

Non-ICC member states like the U.S. do not have a legal obligation to arrest suspects indicted by the Court. Nor does the U.S. need to offer any defense for rolling out the red carpet for fugitive visitors. Nevertheless, the moral opprobrium of being indicted by the world’s most authoritative international criminal tribunal for grave violations of the laws of war, human rights activists argue, should render the visits of Putin and Netanyahu to American soil—even for the protected purpose of addressing the UN General Assembly—unthinkable. In fact, back in September 2013, when Bashir, citing his right under the UN Headquarters Agreement, requested a visa to address the annual General Assembly meeting, human rights groups called on Washington to oppose his entry, lest images of the Sudanese leader walking free in New York City irreparably harm the ICC’s authority. Similar calls were made to the UN Security Council, which, in 2005, referred the atrocities in the Darfur region Sudan for ICC investigation.

The combination of pressure from the broad-based, bipartisan Save Darfur movement and the resonance of the ICC charges against the Sudanese leader for war, crimes, crimes against humanity, and genocide prompted the Obama administration to successfully press Bashir not to visit New York. This occurred during Washington’s on-again-off again détente with the ICC. It was also an era when concern for human rights abuses, at least in certain conflicts like Darfur, carried import at the highest levels of American government. As a consequence, U.S. officials feared the embarrassing optics of allowing the Western-reviled Bashir—implicated in atrocity crimes that had killed some 300,000 people and displaced 2.7 million more—to flaunt his impunity on U.S. soil. In 2015, Bashir again threatened to pay a visit to the UN. But again he stayed home in Khartoum. Bashir’s caution may have been influenced by uncertainty. Given the genocide charges against him, some pro-ICC advocates argued that the 1948 UN Genocide Convention obligated U.S. authorities to supersede its obligations under the 1947 UN Headquarters Agreement and arrest Bashir upon arrival in New York.

The Obama administration worked to keep Bashir from visiting the UN, though not going so far as to deny him a visa. By contrast, the Trump administration has no qualms in welcoming Netanyahu to New York later this month. (For his part, Putin has no plans to attend the upcoming General Assembly meeting.) In fact, the Netanyahu warrant has done nothing to dilute Washington’s military and political support for Israel’s longest-serving prime minister during the protracted Gaza war. That Netanyahu stands accused of being the first head of government charged by the ICC with using starvation as a weapon of war has also not given Trump pause. On the contrary, the American president has doubled down on his campaign of retribution against the ICC, recently sanctioning two additional ICC judges for what the State Department characterizes as “transgressions against the United States and Israel.”

The Obligations of the U.S. as Host State of UN Headquarters

There is a straightforward, legal argument for the U.S., as host state, to grant Netanyahu a visa in order to address the UN General Assembly. However, legal experts say there is no justification for barring Abbas—an act that seems largely intended to punish the Palestinian Authority leader for his campaign to garner recognition of Palestinian statehood as well as his earlier efforts to trigger an ICC investigation of Israeli military conduct. In any case, Abbas has condemned Hamas for carrying out the 7 October 2023 massacre of 1,200 Israelis and the kidnapping of 250 others.

For better or for worse, the UN Headquarters Agreement allows all leaders and their representatives to travel to the UN in New York, except in highly exceptional circumstances. In this regard, the U.S. has a duty to act as host rather than as a gatekeeper that uses the lever of visas to award allies while punishing adversaries. Trump’s decision to politicize who can and cannot travel to the UN headquarters not only risks further emboldening Israel’s war in Gaza and exacerbating the famine. It also threatens to undermine the vision of the UN General Assembly as a forum of sovereign equality and “a sanctuary in the service of peace.”