Mayya Chaykina join JiC for this post on the issue of head of state immunity and the prosecution of Venezuela’s Nicolás Maduro. Mayya is a master’s student in law at Sciences Po Paris. Her work focuses on international criminal law, mass atrocity prevention, and international human rights mechanisms.

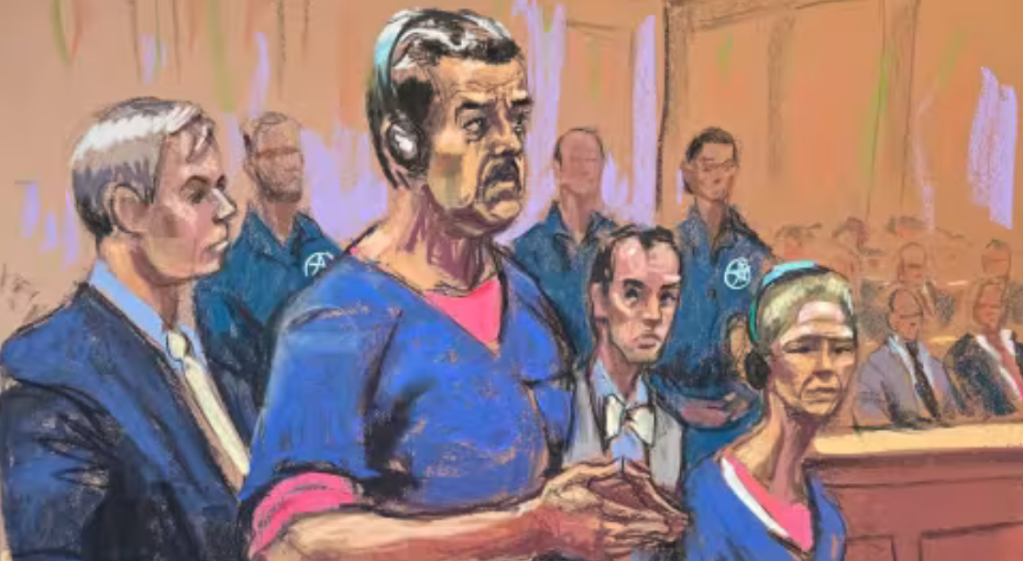

After months of threats of using armed force against the Government of Venezuela, United States forces capturedVenezuelan president Nicolas Maduro and his wife on January 3, 2026. Officials have claimed that the operation was in support of the recently unsealed indictment, which charges Maduro with “narco-terrorism conspiracy”, “cocaine importation conspiracy”, and “possession of machineguns and destructive devices”.

The legitimacy of the criminal charges, however, remains in question. Under the doctrine of immunity ratione personae, or head-of-state immunity, certain officials enjoy immunity from the exercise of foreign criminal jurisdiction for all acts committed in both a private and official capacity during their time in office. Acknowledged by the International Law Commission (ILC) and the International Court of Justice (ICJ), head-of-state immunity applies to a troika consisting of Heads of State, Heads of Government, and Ministers for Foreign Affairs.

Maduro will undoubtedly raise such an objection to the prosecution. On the other hand, the prosecution will likely argue that, given the United States’ non-recognition of Maduro as a legitimate leader, he is not entitled to head-of-state immunity. This analysis will consider the tension between these two questions, ultimately demonstrating that Maduro is entitled to immunity under the current international legal framework and the aims of the immunity doctrine.

The relevance of recognition

Similar issues were raised in United States v. Noriega, a 1997 case before the Eleventh Circuit concerning former leader of Panama Manuel Noriega. Facing charges of drug smuggling and money laundering, Noriega argued that he was entitled to immunity as the de facto leader of Panama. Despite his claim, both the district court and the court of appeals rejected his head-of-state immunity claim as the U.S. “never recognized Noriega as Panama’s legitimate, constitutional ruler”.

As noted above, it is likely that similar claims will make their way before courts in Maduro’s case. The U.S. was the first country recognise Juan Guaido as the interim president of Venezuela after the contested 2018 elections, despite the fact that Maduro remains recognised as president within the United Nations.

Mirroring the courts’ logic in Noriega, the prosecution is thus unlikely to be deterred by head-of-state immunity claims where the U.S. does not recognise Maduro as the legitimate Head of State. However, the question of whether this non-recognition is a legitimate barrier to immunity claims remains controversial under the existing international legal framework, which has been examined both by other national courts and international entities.

The risk of instrumentalisation

Such questions have previously been considered in greater depth by France’s highest court. In a July 2025 decision, the court rebuked arguments rejecting head-of-state immunity based solely on recognition of certain officials.

In stating that making immunity conditional on recognition would grant States discretionary power to authorise criminal proceedings against foreign Heads of State, the court decided that a unilateral act of non-recognition cannot affect immunity ratione personae for a given Head of State. To act otherwise would go against customary international law.

The United States’ recognition, or lack thereof, of Maduro as the legitimate head of state therefore should not be considered to have bearing on whether head-of-state immunity may apply. Indeed, the “discretionary power” that the French court warned against would only further contribute to the risk of instrumentalisation of criminal proceedings. Should head-of-state immunity be linked to the recognition of a Head of State, this would create a structural fissure where other states would be empowered to strategically withdraw the recognition of certain officials to justify intervention and weaponised criminal proceedings.

Maduro’s indictment and the aims of international law

Under the existing international legal framework, Maduro’s head-of-state immunity theoretically remains untouched. Even if the Trump administration attempts to argue that Maduro is no longer the Head of State, as noted by certain scholars, Vice President Delcy Rodriguez has affirmed that Maduro is the “only president” of Venezuela after her swearing-in on Saturday. The exercise of foreign criminal jurisdiction – here, his prosecution in the United States – is misplaced and contrary to the application of the rules of international law concerning immunity for State officials.

The debate around Maduro’s indictment further shines a spotlight on the very purpose of head-of-state immunity in international law. In its commentary to Article 4 of the draft articles on immunity of State officials from foreign criminal jurisdiction, the ILC considered that Heads of State have a special position that place them “in a special situation of having a dual representational and functional link to the State in the ambit of international relations”. These officials therefore represent the State in its international relations simply based on their office.

Given that the sovereign equality of States is “the very foundation of immunity of State officials from foreign criminal jurisdiction”, as affirmed by the ILC in its general commentary, the goal of granting immunity is to protect the rights and interests of the State in question. Ignoring head-of-state immunity while simultaneously using military force on Venezuela would thus raise thorny questions in relation to the goals of the international legal structure and upend the very basis of the international rule of law.

A place for functional immunity?

Despite the current international rules on head-of-state immunity, should the U.S. reject such a claim, the indictment’s framing of Maduro’s alleged criminal acts as emanating from his official power may cushion the fall.

Even in the case that head-of-state immunity is rejected by U.S. courts, the indictment claims that Maduro “leveraged government power to protect and promote illegal activity”, implying the use of his official powers in the alleged criminal activity. Immunity ratione materiae, or functional immunity, exists alongside head-of-state immunity to protect state officials from foreign criminal jurisdiction for acts performed in their official capacity. Extending even after the individual leaves office, Maduro could well bring up functional immunity as a shield against the U.S.’ exercise of jurisdiction.

The doctrine has already been examined in the U.S. by the Fourth Circuit in Yousuf v. Samantar, recalling that functional immunity for an official applies on the basis of “official acts performed within the scope of his duty”. Seeing as the indictment in Maduro’s case explicitly links the alleged criminal acts to his office, especially for the charge of drug trafficking, he could therefore be shielded from jurisdiction through his entitlement to functional immunity.

Whether under categorised as ratione personae or ratione materiae, the existing framework of immunities under customary international law insulates Maduro from the exercise of foreign criminal jurisdiction, including that of the United States. His prosecution would signal an upheaval of the international rule of law, including the very aims of the immunity doctrine. Whether international law will be respected in the coming days remains to be seen – and all eyes are on the United States.

Pingback: Snatching Maduro was all about the spectacle - Abruzzo News

Pingback: Snatching Maduro was all about the spectacle – Top10ETNews.com

Pingback: Snatching Maduro was all about the spectacle

Pingback: Blood for stonks - Wilson's Media

Pingback: Blood for stonks - glowvoyages.com