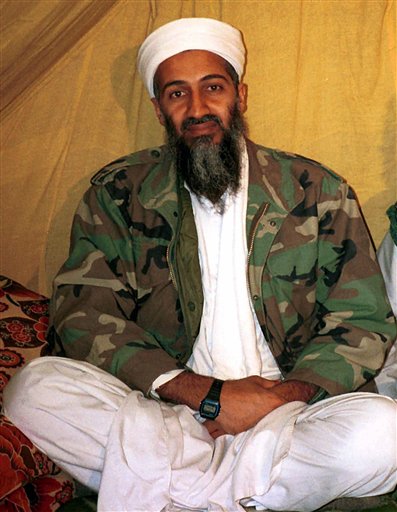

Last night, US President Obama announced that a US special mission had killed Osama bin Laden. Many had described bin Laden's death as "justice" (Photo: AP)

Last night, President Barack Obama announced to eager audiences around the world that America’s most wanted man, Osama bin Laden, had been assassinated. Obama described bin Laden’s death by declaring that “justice has been done.” People around the globe are echoing this sentiment – that bin Laden’s death amounts to “justice”.

Looking at my twitter feed and facebook page, dozens of people are invoking the same notion of justice in bin Laden’s death. Leaders and former leaders around the world have also expressed their views:

George W Bush: “The fight against terror goes on, but tonight America has sent an unmistakable message: No matter how long it takes, justice will be done.”

Tony Blair: “The operation shows those who commit acts of terror against the innocent will be brought to justice, however long it takes”

Canadian PM Stephen Harper “death of Osama bin Laden…secures a measure of justice.”

Kenyan President Mwai Kibaki: The killing of Osama Bin Laden is an “act of justice” for the victims of the 1998 bombings at the US embassy

Executive director of the 9/11 Commission, Philip Zelikkow: “We take a great deal of satisfaction in the news that Bin Laden has been brought to justice.”

Former US Vice President Dick Cheney: “bin Laden has been brought to justice…Today, the message our forces have sent is clear — if you attack the United States, we will find you and bring you to justice.”

But is bin Laden’s death really “justice”? Can killing someone ever be justice? If so, what type of justice is it? If it is just to assassinate bin Laden, who will surely go down as one of history’s most brutal antagonists, shouldn’t that mean that killing Gaddafi amounts to “justice” as well?

First, it is important to note that the legality of assassinating bin Laden rests on shaky grounds, at best. The US justifies killing members of al Qaeda by virtue of being at “war” with terrorism and thus considering al Qaeda operatives as “enemy combatants”. Nevertheless, the legality of targeting individuals with extra-judicial assassinations under international law is precarious. The US has recognized this fact in the past.

Of course, this is not to say that justice equates with what is legal or that what is legal equals what is moral. In 1964, Judith Shklar, warned us of the dangers of legalism, conflating morality with law which risked neglecting or obscuring context.

The instinct of those celebrating bin Laden’s death is that some things, or better some people, are so exceptionally bad that they make law irrelevant. The legality of killing bin Laden doesn’t really matter, it is the “right thing to do” and therefore constitutes “justice”.

Justice is more complicated than it is simple. Justice may be retributive, restorative, distributive, or procedural. For some, justice is primarily moral, for others it is legal, and for others still it is emotional. For many it is all of the above and there may be no difference between the moral, legal and emotional arguments for what is just.

If the “justice” of bin Laden’s death cannot be supported by international law, what kind of justice is it? What people appear to be invoking is a sense of physical, non-legal retributive justice: the killing of bin Laden is his due punishment. The extermination of his life avenges the lives he extinguished. And it must be reiterated, that this was always about killing bin Laden. The US special operations mission was to kill bin Laden, not to capture him.

In some ways, the sentiments of so many around the world is understandable. It seems impossible to blame those who suffered so much loss at the hands of bin Laden, in the US and across the globe (including in Afghanistan and Pakistan), for wanting revenge. It is hard to tell a relative of a victim who has only ever wanted bin Laden “caught and killed” that her desire is wrong. Interestingly, UK Opposition Leader, Ed Milliband appeared to understand this. Rather than saying that bin Laden’s death constituted an act of justice, Milliband stated that:

“For the victims of 9/11 and their families, nothing can take away the pain of what happened but this will provide an important sense of justice.”

There is little doubt that the observation by International Law Professor, Geert-Jan Knoops, holds true: “Naturally, no court in the world will tick off the Americans for this.” Nevertheless, the international community would be remiss to equate killing individuals, even individuals as evil as bin Laden, with “justice”.

The international community has come a long way in establishing systems and institutions of international justice. There is little place for extra-judicial assassinations within these structures. In the coming days, there will no doubt be much discussion as to whether killing bin Laden was necessary. There is a legitimate argument to be made that it would have been more just and beneficial to his victims and survivors had bin Laden been captured alive and brought to trial.

The chief executive of the UK Muslim organisation the Ramadhan Foundation,Mohammed Shafiq, argued the point:

“Osama Bin Laden has been responsible for preaching hatred and using terrorism to kill innocent people around the world and it would have been more suitable for him to be captured alive and put on trial in an international court for the crimes he has committed. Victims of terrorism by al-Qaeda should have had the chance to see him brought to justice.”

At the same time, as so many rejoice in the assassination of bin Laden, there is an ongoing and passionate debate about what the international community can and should do about Libyan leader Gaddafi. This has only been intensified by the recent bombing of a villa in Tripoli that, according to reports, very nearly killed Gaddafi and killed his youngest son, Saif al-Arab Gaddafi and three of his grandsons. Should Gaddafi be the target of NATO strikes? Is it permissible under international law? Is it the right thing to do?

Just two nights ago, a villa where Gaddafi was present, was bombed by NATO (Photo: Louafi Larbi/Reuters)

The assassination of bin Laden is very relevant to this discussion. If killing the al Qaeda leader is permissible and just because he is exceptionally brutal and the US is fighting a “war against terrorism”, making bin Laden an “enemy combatant”, then it should hold that killing Gaddafi is just and permissible as well.

Yet, many who would describe bin Laden’s death as “justice” would not be in favour of assassinating Gaddafi. How do they square that peg? Further, the involvement of the ICC in Libya, complicates matters. As Alana Tiemessen noted last night in a discussion about the repercussions of bin Laden’s assassination on the future of Gaddafi, we “do not want to see an ICC trial and assassination put forward as moral and legal equivalents.”

These developments also have profound implications on the ‘assassination norm’. Kenneth Payne notes that recent work on the subject suggests that:

“the norm against assassination is weakening in recent times, the product of more prevalent and challenging terrorist and irregular adversaries.”

Clearly this applies to the case of bin Laden. Does his assassination signal a further weakening of this norm? Is the international community moving towards accepting that assassinating adversaries is permissible because they are particularly difficult to defeat? What does this mean for the future conduct of warfare and for developments in international justice? There is barely a sliver of doubt that killing Gaddafi would send the international community further down the road of a pro-assassination norm. Many are rightly skeptical that this is a road we should travel down.

The killing of bin Laden makes it even more vital and pressing that Western leaders clarify their position on targeting Gaddafi and articulate what the substantive difference between targeting bin Laden and targeting Gaddafi is. While it may be argued that bin Laden is indeed an “exceptional” case, a move away from international law towards special ops missions and bombings targeting particular individuals would not be justice. It would be a regression of justice.

To a remarkable extent, it has been justice which has guided the recent seismic challenges to status-quo international politics. Nowhere is this more clear than in the Middle East. But it is not time to be complacent about what justice is and how we can achieve it. It is high time that we tackle many of the “loose ends” of international justice, including the targeted killing of individuals.

In the end, it is understandable that many, especially victims and survivors of bin Laden’s brutality, view his assassination as having served justice and even constituting justice itself. Justice can be very personal. What is just and what justice requires is often subjectively constructed by personal experiences. The death of bin Laden has no doubt stirred our emotions and there is little doubt that a world without bin Laden is a better world. But calling the extra-judicial assassination of any individual, no matter how despicable, “justice” may not necessarily be a good thing and it may not necessarily serve justice.

For more on the legality, legitimacy and justice of bin Laden’s death, check out this compilation of perspectives.

U.S. Senator John McCain said it was okay to Muammar al Gaddafi was murdered by a targeted air strike. NATO bombs had killed after Libyan detail on Saturday a son of the dictator. Meanwhile, the youngest son of Libyan ruler Moammar Gaddafi, Saif al Arab al Gaddafi, was killed on Saturday evening during a NATO air attack. This was announced by a spokesman for the Libyan government in Tripoli on state television. Also 3 grandchildren have been killed. I really wonder what kind of a strategy. to shoot at tanks is probably the one thing, but to kill children. Well, with what is moral since traded.

You have articulated much of the concern I have as a lawyer and advocate of international criminal justice on learning of Osama Bin Laden’s death. Living in New York right now it is hard not to have some kind of intuitive retributive reaction, but any assassination or killing should give rise for reflection.

Instead of measured reflection on whether the circumstances of the operations justified the deaths which occured last night (which they may have) I think the most inappropriate reaction I have seen so far is the recent tweet from @AmbassadorRice “I am bursting with pride in our brilliant special forces, intelligence experts, our President and all who brought UBL to justice!”

Terrorism and the targeting killing of civilians is a heinous act and one which is criminalised in every jurisdiction I know of -most fundamentally as murder. There is very little doubt about the links between Bin Laden and terrorist acts of 9/11 and others attacks, however, responsibility for heinous acts does is no justification for extra-judicial killings of those deemed responsible. Bin Laden had a fundamental belief in a cause and a willingness to kill those he perceived as his enemies in order to further his ends; I wonder what would have happened if the US Administration had not followed the same logic and instead adopted a rule of law strategy. Terrorism, and the murder of civilians, is after all a supreme crime. It should be treated as such.

In his opening address at the Internatioanl Military Tribunal at the end of WWII Justice Jackson articulated the what has become the mantra of international criminal justice:

“That four great nations, flushed with victory and stung with injury stay the hand of vengeance and voluntarily submit their captive enemies to the judgment of the law is one of the most significant tributes that Power has ever paid to Reason.”

Had the top echelon of the Germany’s National Socialist apparatus been executed or killed during capture I imagine it would have been to much applause. I am sure most commentators would have viewed such treatment as just and a manifestation of justice, and a few perhaps would have been bursting with a pride similar to @AmbassadorRice’s. However, back in 1945 heinous individuals were treated as criminals and the world is a better place because of it. There is no reason why Osama Bin Laden was any different.

I’ll keep it short and sweet. Might is right and ends justify the means. Superpowers don’t operate under the same rules of ‘ordinary’ countries faced with terrorism.

I can’t wait for AI, HRW, ICG and the rest to demand and get international, UN-sanctioned investigations into OBL’s final hours! 🙂

Fancy a bet?

A few thoughts:

1. You’ve really got to be a bit more careful parsing out what justice means before we can get to statements like:

“While it may be argued that bin Laden is indeed an “exceptional” case, a move away from international law towards special ops missions and bombings targeting particular individuals would not be justice. It would be a regression of justice.”

This presumes two things, first that justice is a feature of the law, or that justice requires following the law and, therefore, the more fully the law is followed the more perfect the expression of justice. And while you suggest that justice is complicated, I think the way in which you suggest it is complicated is problematic.

“Justice may be retributive, restorative, distributive, or procedural. For some, justice is primarily moral, for others it is legal, and for others still it is emotional. For many it is all of the above and there may be no difference between the moral, legal and emotional arguments for what is just.”

There are two issues here. First, the difference between retributive, restorative, distributive or procedural justice is not merely a difference between interpretations of what justice is, or means, but different contexts in which justice is pursued. The implication being that you could have differing understandings (or even theories) of retributive justice, for example, but all of which address the question of justice in terms of punishment and repayment for wrongs committed. Importantly, international justice is a different sort of distinction, and could include questions of retributive, restorative and other forms of justice.

Second, I don’t think the distinction between moral, legal and emotional accounts of what is just holds up very well – I don’t think many of us would think that justice is reducible to one of these accounts or that they form a coherent whole. I say this because there’s an ambiguity here regarding what justice is. I’d say that we can think of justice in these difference contexts (moral versus legal, etc) but that these are simply different ways of thinking about what is the proper thing to do. Further, a definition of justice by itself will never tell us which of these perspectives to take on.

While I’m well aware that all I’ve accomplished here is muddying the waters, I think these sorts of distinctions need to be made to even know what “we” are objecting to in pronouncements that justice has been done by killing bin Laden, and certainly before we can readily claim that international justice cannot allow for assassinations of this kind.

What is objectionable in the claim that justice has been served thought the assassination of bin Laden? Those claiming justice has been done seem to be endorsing a view that he has gotten what was deserved and that his death is the appropriate punishment for his actions. While I can see why that is unsatisfying from a legal perspective or for anyone opposed to the imposition of death as punishment, it doesn’t strike me as inherently problematic for a conception of international justice, or even for international law – at least for more conservative/state-centric accounts.

2. Even in parsing out the different (and contested) meanings of justice, there’s a danger in too quickly jumping to the claim that killing bin Laden was a failure of, or incompatible with, international justice.

I’m not unsympathetic to the claim that justice is not served by killing bin Laden at his compound, but I’m also sceptical about the motives for insisting that he should have been captured and tried – trials, especially international ones, are political acts and the desire to legalise the act of holding to account, of delivering justice, is hardly innocent or unproblematic.

Again, I might be inclined to pursue justice against bin Laden through the law and via the medium of a public trial (my mind is sincerely not made up on the matter), but my reasons for that are not that I want justice to be done and only justice delivered in this way is acceptable – my support would be based upon the further ends that such a pursuit of justice bring with it, such as affirming the authority of international law, displaying the procedures of legal and formal justice, etc.

3. The comparison between Gaddafi and bin Laden is problematic (as is the implied slippery slope leading from one to the other) – even as the issue of targeted strikes needs to be addressed, as you rightly point out.

I don’t see bin Laden as setting a precedent here – the US has been remarkably clear in making an exception of the lifting the assassination rule for “enemy combatants” when fighting terrorist organisations responsible/complicit in the 9/11 attacks. Which isn’t to say those exceptions are not problematic and open to abuse, I just don’t see much danger of it the Gaddafi case as the justifications are simply to different. Agree with it or not, the logic that the US has to keep open the option of assassinating terrorists/enemy combatants is different than one that says Gaddafi can be assassinated because he’s suspected of war crimes and has been hard to track down.

If I may condense Joe’s learned treatise into a more digestible format.

The US can and does change the rules under which it allows itself the privilege of killing it’s enemies – with or without a trial.

Interesting viewpoints articulated here. I don’t have much to add from a strictly legal perspective because I think we are into a long-term, shadowy type of war which is waged by non-state actors (i.e. the likes of Osama) against certain nation-states and thus we’re into a zone where the normally recognized laws of war don’t necessarily apply. From a purely emotional point of view, most people, including me, instinctively feel that to kill a known terrorist who had organized and funded terrorist acts (killing a large number of defenceless people, suddenly and without warning) is a good thing, if only because it forever removes him from the equation and because the “eye for an eye” instinct is so deeply engrained in most of us.

From a distributive justice point of view, if I am not mistaken about the definition of ‘distributive’, a certain number of people who had been victims or been agrieved by the perpetrator of a crime (or numerous crimes, in this case), must both “get” something out of an act of justice, such as an increased feeling of safety, monetary goods, or even the perception that the scales of justice have swung in their direction. Whether the friends, relatives and former partners of the people who had died on 9/11 and in other acts feel that this had somehow answered some of the concernes and alleviated their personal tragedies, I leave it up to all those people. Their reactions are not going to be uniform or entriely predictable.

There is a big, big unspoken issue here, as well: whether bin Laden or even one of his lieutenants could have ever received a fair trial, anywhere. I imagine the US would have wanted to try him at home. No one would have taken up bin Laden’s case. Just like defending Col. Russel, in Belleville, would have been an impossible job. And putting bin Laden on trial at ICC in the Hague would not have been feasible, either, as he did not operate in the same realm as former heads or ministers of states that faced “crimes against humanity’ charges, like Milosevic or Charles Taylor. Those men had been in command of armies and militias. bin Laden was merely the organizer and later the figurehead of a loose coalition of occassional terrorists, most of whom blended in with normal civilians. Difficult to try him in a state context. Thus killing bin Laden saved the Americans the immense trouble of finding where and how to try him. You’d need to look up Carlos the Jackal for a precedent…but then again, it’s not exactly an equivalent.

Last but not least, there is the almost unspeakable issue of assigning culpability to many of the people inside Pakistan, whether local chieftains, agents in the Pakistani secret service, local police who had all played both sides and ensured Osama stayed hidden or sufficiently out of reach. In Roman times or medeival times, they would have all been judged as co-conspirators by the victor (United States of A) and would have been subject to immensely bloody reprisals – and would have had to save their skins by publicly pledging loyalty to the victor. They should consider themselves lucky we no longer live in those times. They truly backed the wrong horse. This is the angle that interests me the most since someone like bin Laden didn get to the top of the terrorist hierarchy by not having friends and not recruiting a large network of passive and active supporters. So my question is – what about Pakistan’s establishment and their culpability?

That would be

Pingback: “The ‘Justice’ of Killing bin Laden and What it Means for Gaddafi” « The Politics of International Justice

Thank you all for the fantastic, thought-provoking comments. I can’t possibly cover them all but here are a few things.

@Tobias – the celebration of death is problematic, I couldn’t agree more. Thanks for bringing up the historical example of Nuremberg in your eloquent comment.

@Joe – this is perhaps the most comprehensive comment I could hope to get on this blog. Thank you so much for that. I agree that the blog may have weaknesses in how far in reaches into “what is justice” and I appreciate your comments on the matter.

With regards to point 3, I don’t agree with the premise that what happens to bin Laden is irrelevant for the future targeting of individuals like Gaddafi. I think it can only have implications unless it made clear how and why Gaddafi and bin Laden are substantively different as military targets. I really believe that bin Laden’s death will have effects on the “assassination norm”

I quoted you a few times in the new post by the way.

@Jan – I also quoted you in the latest post. Thanks for this enlightened comment as usual.

@Mango – you bring up something very interesting in what AI, HRW, ICG etc. will say about bin Laden’s death. Thanks for bringing that up and for the comments!

Very thought-provoking article as well as comments. I discussed the issue of reactions to Bin Laden’s death on my own blog http://littleexplorer.wordpress.com/2011/05/02/reactions-to-bin-ladens-death-on-yom-ha-shoah/ but I completely (and on purpose) avoiding discussing them from a legal standpoint. I believe that all of these legal considerations are applicable to a certain extent since, as we know, law is about interpretation – and this is even more true when we’re dealing with IHL and IL. These discussions are, in my opinion, almost purely theoretical precisely for the reason summarized effectively by “Mango”, i.e. “The US can and does change the rules under which it allows itself the privilege of killing it’s enemies – with or without a trial.”. Besides, I very strongly doubt that any case would every arise (at least, on the international level at the ICC) charging the U.S. with international crimes.

One further observation, which came up while reading this article: are we sure that the death of Bin Laden would be a ‘punishment’ for him / Al-Qaeda / his supporters? If we consider the main strategy of terrorism is martyrdom, then perhaps killing him could even be perceived as victory of terrorism technique: in other words, given the ideology backing Bin Laden, only shutting him in jail for the rest of his life would have been “real justice”, in my opinion (although another debate may start on this point too, but I’ll restrain myself!).

P.S. Sorry for the typos… (I’m a little tired)

The united state has done a good job