Thomas Obel Hansen joins JiC for this fascinating guest-post on the internal and external pressures facing the ICC in the Kenya cases. Thomas is an independent consultant and an assistant professor of international law with the United States International University in Nairobi, Kenya.

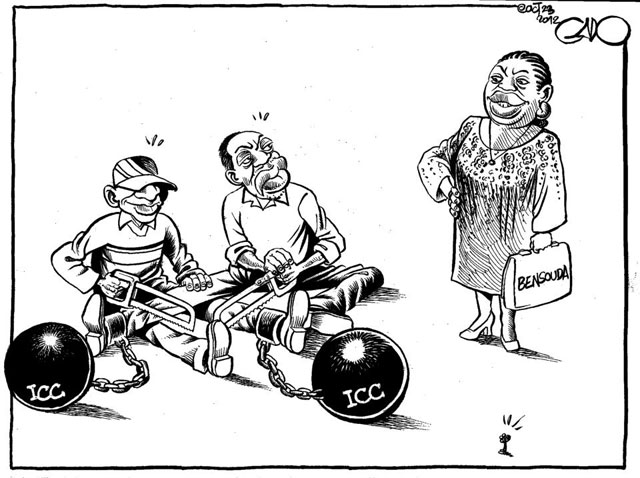

Prosecuting a sitting Head of State and his Deputy at the ICC was always going to be a complicated task. While the ICC can claim success in that the first of the two Kenya trials commenced Tuesday last week with William Ruto, the Deputy President of Kenya, present before Trial Chamber V(a), it is no secret that the trials are marred with controversy.

As the Prosecution continues to express concerns over the level of witnesses intimidation in the Kenyan cases, the Ruto Defence used his opening statement to deliver an all-out attack on the Office the Prosecutor, claiming that it is guilty of performing a “lazy prosecution”, being “indifferent to the truth” and constituting part of a “glaring conspiracy of lies”. At the same time, political leaders in Kenya – supported by countries in the region – are adding unprecedented pressure on the Court to have it their way. The African Union is reported to have planned an extraordinary summit to (once again) discuss what can be done to end the Kenyan ICC cases. And, as Mark discusses here and here, Kenya’s Parliament has been pushing for a withdrawal from the Rome Statute, although any action by the Kenyan government to this effect would have no impact on the obligation to cooperate with the Court with respect to the ongoing cases.

But there is another aspect to the enduring mobilization against the ICC which has so far received little attention, namely that political actors are increasingly focused on influencing the outcome of specific proceedings before the Chambers. This begs the question: is the Court able to deal with such pressure and protect its institutional interests?

During a status conference on September 9 – just one day before the trial hearings in the Ruto & Sang case commenced –Presiding Judge of Trial Chamber V(a) Eboe-Osuji announced that the Chamber had considered the matter of the two Kenya cases running simultaneously or on alternating days and had come to the conclusion that “running the cases simultaneously will not necessarily expedite them”. Accordingly, Judge Eboe-Osuji stated that it was “the Chamber’s preference that the Court sits on a four-weeks alternating period”.

Keeping in mind that two of three judges who sit on the Trial Chamber that is handling the Ruto & Sang case also have a seat in the Chamber that is handling the Kenyatta case, this might have seemed a reasonable decision, had it not been because the same Chamber, in a ruling of 29 August, rejected Ruto’s request that the Chamber sits on alternating periods on the basis that it would not be “an efficient way to conduct the proceedings in the present case”.

Curiously, this change of mind took place only one day after President Uhuru Kenyatta, whose trial is currently scheduled to commence on 12 November this year, made it clear that he would only continue to cooperate with the ICC if the Court’s schedule suits him:

“They should not make it impossible for the sovereign nation of Kenya to be led as its citizens democratically chose…We will work with the ICC but it must understand that Kenya has a constitution and Ruto and myself won’t be away at the same time…If they want us to cooperate, they must ensure that when Uhuru is there (at Hague) Ruto is in the country.”

One can’t help but speculate that the Trial Chamber’s reconsideration of the issue may somehow have been influenced by Kenyatta’s remarks, a suspicion that Judge Eboe-Osuji himself made no attempts at proving wrong when he failed to clarify what had made the Chamber change its mind.

The danger with making such decisions is that they easily give the impression that it is the accused, not the judges, who are in charge of the proceedings. The ICC’s legitimacy is not only contingent on the Court making sound decisions, but also on the appearance that these decisions are impartial and based on the Court’s preferences – not the accused’s.

In a separate development last week, a number of African states engaged in what appears to be a well-coordinated attempt at influencing the Appeals Chamber’s soon-to-be-expected ruling on the Prosecutor’s appeal of the Trial Chamber’s decisionto grant Ruto’s request for excusal from continuous presence at trial. Almost simultaneously, Tanzania, Rwanda, Burundi, Uganda and Eritrea filed applications with the Registry to be granted leave to file amicus curiae briefs under Rule 103(1) of the Rules of Procedure and Evidence. This is, to my knowledge, the first time that States Parties – not to mention non-States Parties – have sought the Court’s permission to file legal observations with respect to ongoing proceedings to which they are not parties and which do not directly affect any of their nationals.

The applications make it clear that it will be submitted that Article 63 of the Statute concerning the accused’s presence at trial must be interpreted in a “broad and flexible” manner. Put in simpler terms, the five States will argue that the Appeals Chamber should uphold the Trial Chamber’s ruling that Ruto, in light of his official functions in Kenya, should be excused from continuous presence at trial.

But there is clearly more to these applications than a wish to provide the Court with legal advice. By way of example, Tanzania’s application emphasizes that “the Appeal implicitly raises the issue of State cooperation”. In a similar tone, Rwanda’s application states that “there has been considerable debate, both at the domestic and international level, about whether non-state parties, such as Rwanda, need to sign the Statute”, and in this regard emphasizes that “the proper interpretation of Article 63 is germane to the current discussion on whether or not to become a state party”. Leaving aside that there are no good reasons to think that Rwanda is seriously considering becoming a State Party, these and other statements made in the applications clearly point to the extra-judicial nature of the anticipated filings.

This raises the question of whether they can be permitted at all. Rule 103(1) simply provides that a Chamber may, “if it considers it desirable for the proper determination of the case”, invite or grant leave to a State, organization or person to submit “any observation on any issue that the Chamber deems appropriate”. However, as Christoffer Wong points out, the Court’s case law has so far emphasized that “amicus curiaeobservations should be limited to matters of legal interest”. In the Kenya cases, Pre-Trial Chamber II allowed amicus curiae observations only on an “exceptional basis”, when it was of the view that such observations would provide “specific expertise” needed by the Chamber.

However, when on Friday September 13, the Appeals Chamber by majority granted the requests, the Chamber simply ignored the question of whether the amicus curiae briefs are likely to be limited to matters of legal interest as well as the question of whether the mentioned States are in possession of any relevant expertise on the matters at hand.

As dissenting Judge Anita Usacka points out, there may be serious implications of allowing observations from State Parties as well as non-State Parties which address issues relating to how judicial decisions may encourage or discourage State cooperation as well as ratification of the Statute.

Most obviously, should the States that drafted the Statute be allowed to influence the outcome of particular proceedings by raising issues that arguably amount to threats of non-cooperation and in other ways touch on fundamental aspects of the relationship between the Court itself and the States that created it? The question goes to the very heart of the Court’s independence and impartiality. As Judge Anita Usacka noted:

“[A] distinction must be drawn between the role of the judiciary, on the one hand, and the role of States Parties, on the other hand… A strict separation between these two roles must be observed in order to preserve the independence of the judiciary. In the circumstances of the present case, the intervention by five interested States of the nature proposed engenders the risk of distorting the judicial process or, at a minimum, creating the appearance that States have inappropriately encroached upon the functions of the judiciary.”

An amicus curiae has been defined as a “personality whose moral authority, scientific or human, is universally recognized and is asked by the judge to provide adequate information to clarify the disputes brought before it.” Notwithstanding that the moral authority of some of the States now involved in the proceedings can be questioned, might it not have been more appropriate had the Appeals Chamber required that the observations be clearly restricted to addressing legal issues relevant to the specific decision? It is not clear how observations that address issues relating to the relationship between the outcome of specific proceedings and particular States’ willingness to fulfill their obligations to cooperate with the Court can possibly be “desirable for the proper determination of the case”, as required by Rule 103(1).

An amicus curiae has been defined as a “personality whose moral authority, scientific or human, is universally recognized and is asked by the judge to provide adequate information to clarify the disputes brought before it.” Notwithstanding that the moral authority of some of the States now involved in the proceedings can be questioned, might it not have been more appropriate had the Appeals Chamber required that the observations be clearly restricted to addressing legal issues relevant to the specific decision? It is not clear how observations that address issues relating to the relationship between the outcome of specific proceedings and particular States’ willingness to fulfill their obligations to cooperate with the Court can possibly be “desirable for the proper determination of the case”, as required by Rule 103(1).

Of course, the Appeals Chamber’s decision to grant leave might just have been a diplomatic exercise aimed at countering a perception that has gained popularity in some circles, namely that the “ICC gives more hearing to the civil society than it does to State Parties”, as the Majority Leader in the Kenyan Parliament Aden Duale, who has been instrumental in the push for a withdrawal from the Statute, recently claimed.

However, as I argue in more detail in this forthcoming case note, the Trial Chamber’s decision was – to put it mildly – based on an innovative reading of the Statute, which downplayed the importance of Article 63(1), according to which “[t]he accused shall be present during the trial”, as well as the intention of the drafters, while emphasizing non-Statutory international law rules, including those relating to privileges of State officials. What is more, the Trial Chamber’s ruling also paid scarce attention to the views of victims. Depending on the outcome of the Chamber’s decision and its reasoning, allowing five States to make submission to the effect that the Trial Chamber was right in affording Ruto special treatment due to his duties as a State official could end up portraying the Court as being more friendly to States that seek to uphold immunity than to those who seek to combat impunity – not to mention those who have suffered from it. As Judge Anita Usacka notes, such one-sided interventions are hardly compatible with the principle of equality of arms and the balance between the parties in the proceedings.

It remains to be seen what significance the Appeals Chamber will afford the observations of the five States. But should the Chamber choose to take into account their extra-judicial observations, this is bound to fundamentally change the relationship between the lawmakers and the judiciary. By allowing that observations are filed relating to the decision’s potential impact on States’ willingness to cooperate with the Court, the Appeals Chamber has already laid the ground for a new conception about the way in which States can legitimately interact with the ICC. Whereas efforts on the Court’s side to counter the perception that it is treating African States unfairly are in principle welcome, the types of interactions endorsed by the Appeals Chamber may ultimately harm the Court’s independence.

The views expressed in this Article are those of the author only, and do not necessarily reflect the views of the organizations with which the author is affiliated.

Amicus curiae or ”political advice”? Legal reasoning even put aside, amicus curiae litteraly come form” court’s friends”. Some countries in the list(Burundi, Rwanda) clearly don’t quality.

Read: ”don’t qualify”.

Great stuff!

Very interesting, Thomas. Do you have a sense of whether Kenya, Tanzania, Burundi, Uganda, and/or other State Parties are mounting a parallel campaign in the Assembly of States Parties itself? The ASP has the authority to modify the Rome Statute or Rules of Procedure and Evidence, which would be another way to shape judicial processes.

Interesting question, Chris. I doubt they will get anything through the ASP in this regard, even if they did try. Of course, any further action on their side will depend on the AC’s ruling. If the AC rules that the TC was wrong in finding that the Statute should be interpreted to allow Ruto’s absence at trial, it would probably be a matter of convincing other States that Article 63 concerning the accused’s presence at trial should be modified, or even deleted. I doubt this is something that many other States Parties outside the region will accept. That being said, it looks like some African countries are willing to go a long way in their attempt at ending the Kenyan cases, or at least make sure that the trials will take place according to the wishes of the accused, so I wouldn’t exclude that they will look at what could be done within the ASP. And maybe this is what they ought to do – as Judge Usacka pointed out in her dissent, it would have been more appropriate had the extra-judicial concerns raised by the five States been brought in that forum, rather than in the context of specific proceedings.

It’s probably time for another recusal of judge Eboe-Osuji. The last one was also brought forward by Karim Khan, incidentally (in the Banda & Jerbo case). I have commented on him and on his personality (as outstanding he is as a gifted writer, legal scholar and academic, as unfit he is for the duties of a presiding judge) elsewhere.

Eboe-Osuji has here quite knowingly issued and motivated a wrong decision (wrong not in the sense of “you know, I would have decided differently”, but wrong in the sense of “utterly UNTENABLE under any possible aspect”), and his weak yet wordy reasoning and his waffling around the core issues rather loudly betrayed his bad conscience.

The politicization that Eboe-Osuji and now also the appeals chamber undertake, is quite understandable and is certainly inspired by the best of intentions. But it is, with a very simple yet very correct word, il-legal. And Anita Ušacka has precisely laid bare in her crisp dissent, why this diplomatic tail-wagging and this assuaging move is NOT within the competence of the ICC. It is necessary, for sure; yet it belongs, as I will add, into the aegis of the Assembly of State Parties, and not of the Court. Silete iudici in munere alieno!

@Bernard: a true Freudian slip, brilliant in its conciseness. However, you might rather think of Eritrea – a brutal and callous paria state if there is any in Africa, indeed worse than Sudan – to make your point.

@Thomas: you would certainly whack any of your students who misses the one and main recent (yet not toooo recent) monography on the topic of his seminar paper. So, why do _you_ miss it in your article entirely? It was authored by Anne Klerks in 2008. A glaring and hardly justifiable (though maybe excusable…) omission in an academic article like the one to the preprint of which you have linked; given that a mere one or two minutes of Google search would have lead you (and the trial chamber V(a)) to it:

http://arno.uvt.nl/show.cgi?fid=81103

@Chris: I think you can trust on Intelmann and on (the shade of) Wenaweser to foil any such ploy in the ASP.

“But there is clearly more to these applications than a wish to provide the Court with legal advice” may be the understatement of the year. The filings of Tanzania and Burundi appear clearly to be drafted by someone else who solicited their signature. Unfortunately, neither country edited the document electronically but tried to do so by hand ( a mistake Tanzania has since sought to correct):

Click to access doc1642403.pdf

Click to access doc1643520.pdf

This case is in many ways a conspiracy theorist’s dream, and nothing should be assumed to be what it is. There appears to be a lot of behinds the scenes maneuvering, selective reporting and selective publicity of proceedings – which makes in-time commentary and analysis particularly difficult.

David, as you are aware, the parties in the two Kenyan cases try to outdo each other with confidential and ex parte briefs (which practice does extend far far beyond the ongoing article 70 proceeding). The trial chambers try to reclassify some of these as public (with redactions), but the funnily clumsy heavy-handedness of the latest redactions (“The witness [REDACTED], who previously [REDACTED], was [REDACTED]. The [REDACTED] application of [REDACTED] was meant to [REDACTED]”) would even give the Court of Star Chamber an undeservedly bad name. 😛

As to the pseudo “parasita curiae” applications, the Kenyan state (holding brief for the accused) sent around the draft, pressing in its characteristic mix of bullying and checkbook diplomacy the other AU states to sign the pettion list. Since the state parties, as I understand – please correct me – do not have direct access to Ringtail, they had to work on the Kenyan-supplied draft, and they did so in a MOST amateurish and inept manner.

Pingback: Justice in Conflict: The Price of Deference: Is the ICC Bowing to Pressure in the Kenya Cases? by Thomas Obel Hansen | Kenyan Asian Forum

Alexander,

Indeed, the range of confidential and ex parte filings and sessions make it difficult to separate public facts, leaked facts and speculation.

Are there any public reports on Kenya soliciting these filings and what they may have promised in exchange? The code of conduct for counsel applies explicitly to both States and amici, and this may raise interesting questions under said code (as well as being of interest to the Appeals Chamber in considering these filings).

Ringtail is purely for document management. The filing templates are simple MS Word documents. One surprising thing about the ICC website is that these templates and instructions for filing don’t seem readily available. However, Kenya has the templates. It appears that Kenya (or whoever it may be that provided the drafts) provided either hard copies or pdfs rather than the MS Word template and failed to make sure that the amici applicants used the Word versions (some did and Tanzania tried to correct this mistake).

In the two Tanzanian applications, I refer to footnote 5 (the last one). Its differing form (firstly with the “fill in here” hint, then without any embarrassing content at all) is an indicator _when_ the printout was originally submitted to the states.

As to the application text, it was definitely NOT drafted and worded in the Kenyan Attorney General’s chambers. And the state party of Kenya also seems no more represented by two English QCs, as it was initially (very unsuccessfully and very expensively).

It is of some further interest that the original draft envisioned a potential *joint* application of many states, providing for a plural nomination throughout the template. The submitters (who are different from the drafters) may thus have distributed it on an occasion when various or even all African states were represented. Only in the end, it was found that no more than 5 states could be, well, “persuaded” to apply, and hence the singular mode of individual application was chosen. Chosen in a great hurry, as is visible.

Alexander’s comments are fascinating, when the case looks like it will not get to its pre-determined fixed outcome, pull all stops, call for the removal of independent judges, attack their rulings and any matter of unorthodox means necessary to ensure the case is fixed and results in only one possible outcome, a guilty verdict absent of any merit whatsoever. That is the hallmark of a kangaroo court.

There is a reason why individuals such as the good professor, writing from his host country and Alexander, who might be excused if he works for the OTP or the OTPs school of witness recruiters and coaches, are relegated to blogging about the ICC’s rulings and why the judge remains and will remain as the presiding judge in the case.

Despite Alexander’s wishful thinking, ridicule notwithstanding, 5 nations and now 6 have filed requests for leave to file Amicus Curie Briefs, so what if they appeared to have used a common template seeking leave of the court? They were granted leave to proceed.

If Alexander and/or the OTP feel aggrieved by the judge’s decisions on scheduling, they are free to respectively file appeals or amicus briefs as well.

For good cause shown, the world over, courts are not inflexible to schedule changes. Across the United States, there are numerous federal and state courts that arguably exhibit standards of high international jurisprudence. Scheduling orders are issued and for good cause shown, accommodate without prejudice parties before the court, be they prosecutors, plaintiffs or defendants. Perhaps in their haste to rush to their foregone pre-engineered and imagined judicial outcome of nothing but guilty, the good professor and Alexander have simply exposed their unreasonable and misplaced contempt for what were reasonable presentations by ALL counsel and decision by the court.

Not only have the duo disregarded the fact that the original schedule was tentative and subject to change but that the various parties met at a status conference and had made prior submissions regarding the schedule desired, and that included the OTP! http://www.icc-cpi.int/iccdocs/doc/doc1640178.pdf and here http://www.icc-cpi.int/iccdocs/doc/doc1643877.pdf — pg 28-29.

The motive behind narrowing down to attack the presiding judge when it is clearly stated “The Chamber received indications from counsel regarding their preferences for the Trial Chamber’s sitting schedule” calls into question the integrity of the individuals making unfounded charges against the integrity of the Judge. Do the professor and Alexander harbor some form of animus or ill will against the Judge or individuals who do not adhere to their belief system where trial is apparently a mock public relations exercise where the outcome is known before it starts? Does “we” – the chamber mean “I” according to the self declared rules of such individuals? Notably no objection from the OTP was registered regarding the schedule.

On the often repeated OTP theme of witness intimidation and bribery, this video is self explanatory. All former witnesses who have gone public on their own volition have similar stories of OTP and NGO witness coaching, undue pressure and coercion. The OTP has failed to bring charges against the very same witnesses, perhaps due to the simple fact that it would incriminate the OTP and its associate agents in the case. http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=mOxt1pPCXxE and in writing: http://bit.ly/1aUPkuM

It would be tremendously ignorant to disregard the simple fact that what happens in Kenya affects the greater East and Central African region. This was clearly evident during the occurrence of the subject matter before the ICC in 2007-08. If there is nothing to hide with the ICC process, then there is no need to be dismissive or uncomfortable about state parties filing Amicus Curie briefs at the ICC. If it is a truly open court then issues before the court should be deliberately openly and on the same platform and if they lack merit or are frivolous, the court is not obligated to adopt or deliberate such issues.

Who is the arbiter and certifying authority on moral authority in today’s world? Is it the western foreign lands and their theorists, whose narrow world view only consists of western idealism, to speak on behalf of entire populaces of African nations before the ICC?

The above comment has been edited. A section of the comment was deemed inappropriate and as going against the spirit of open, free and fair debate on the site. I do not take this decision lightly as we seek to interfere in the comments of readers as little as possible. The subjects covered on this site are sensitive and often evoke strong feelings. This makes it all the more important for readers to remain courteous and respectful to each other. Any comments which are perceived as unduly intimidating or aggressive will be deleted at the discretion of JiC authors.

7 nations by now, not just 6. Given your position with regard to the accused on whose behalf you do PR, you had of course ex officio access to the submissions before they were uploaded to Ringtail this evening. The legal incompetence of the applying states however is breathtaking.

More illustrations of the sloppiness in how this is handled:

– Burundi asks for an extension of time to file its submissions, after Rwanda files submissions on their behalf

– Nigeria submissions are signed “Federal Republic of Nigeria”, not by any individual.

At a discussion at International Peace Institute, I asked the Kenyan ambassador to the UN directly whether Kenya was involved in soliciting these filings and how the Kenyan government ensures separation between the trial of these individuals and government functions, mindful that it is these individuals and not Kenya as such on trial. He didn’t answer the question, but he did state that in his view it’s not just two individuals but the Kenyan head of State on trial.

The Kenyan UN ambassador (Macharia Kamau) had been dishonored by his state before, so of course he did not answer you. The UN submission in May 2013 was not worded by himself, and it was flatulence on wheels – the piece was concocted in the Attorney General’s chambers, in an amazingly incompetent and buffoonish way, exposing Kenya to widespread ridicule. Not to speak about the legal idiocy of it. His own diplomatic writing style is far more professional than this rodomontade (and his English is correct, too).

In a preceding step of embarrassment, his deputy head of mission (Koki Muli) had been ordered to blow some hot air, which he himself had likely refused. Yet only in November 2012, she had still publicly taken the opposite position – an amazing display of turncoatism and selling out.

http://www.standardmedia.co.ke/?articleID=2000070313

Pingback: The intrigues surrounding Kenya's plan to withdraw from the ICC - HapaKenya

Pingback: KENYA : What’s at stake as Kenya weighs withdrawal from the International Criminal Court | Metro Afrique