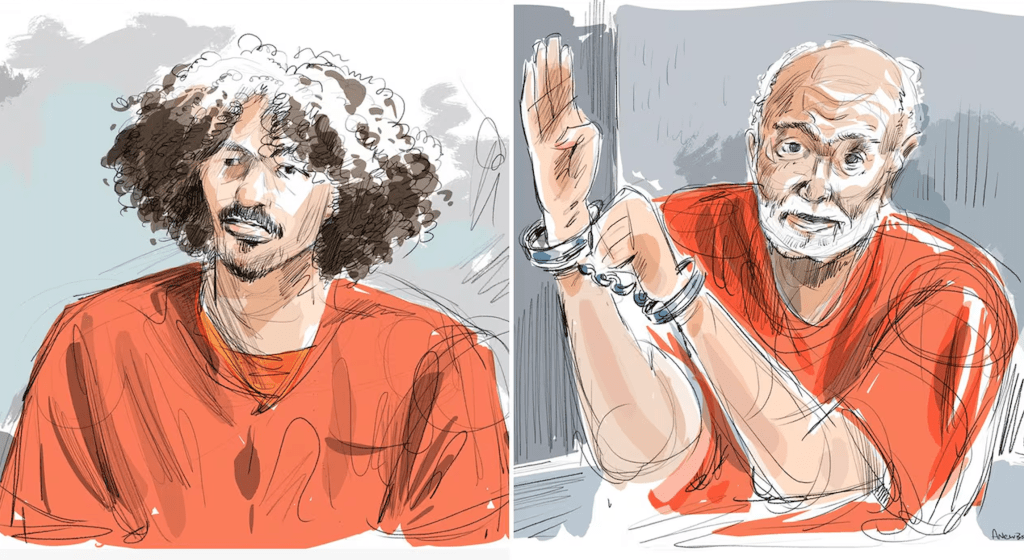

In 2018, Ahmed Fouad Mostafa Eldidi arrived at Toronto’s Pearson Airport. After his application for refugee status was accepted in 2019, he received a work permit. He then became a permanent resident in 2021. Subsequently, the Canadian Security Intelligence Service gave his application a “favourable recommendation”, and Mr. Eldidi was granted Canadian citizenship in May 2024. Just two months later and after a tip from France, he was arrested with his son for allegedly planning a terrorist attack in Toronto. It then came to light that Mr. Eldidi had apparently appeared in a 2015 promotional video by the Islamic State, hacking the limbs off a prisoner with a sword – an act which likely constitutes a war crime.

This series of events has led to obvious questions: How could Canada not only let Mr. Eldidi into the country, but fail to identify him as a possible security threat during two separate national security screenings? And why did the Canadian authorities not know of his alleged 2015 atrocities?

These questions are being hotly debated by politicians. In House of Commons committee meetings and on social media, the political bluster over Mr. Eldidi’s case is palpable. But it is also unhelpful. Blame and excuses cannot prevail over introspection and self-reflection. The finger-pointing in Ottawa is a distraction from the fact that both Conservative and Liberal governments are responsible for leaving Canada susceptible to perpetrators of atrocities entering the country.

What should be questioned, and answered, is what Canada did not do that left the country vulnerable to infiltration by atrocity perpetrators and what it can do to avoid a repeat in the future.

Background: A bi-partisan refusal to address international crimes

Under the principle of universal jurisdiction, enshrined in the Crimes Against Humanity and War Crimes Act of 2000, Canada can prosecute perpetrators of war crimes abroad even if they or their victims are not Canadian citizens. But since the 1990s and the failure to convict a number of alleged Nazis living in Canada, Ottawa’s preferred approach has been to either ignore alleged war criminals living in our midst or to deport them. And when it does ‘send them back’, it does so without any guarantee that they will subsequently be investigated or prosecuted for their crimes.

During the Conservative government of Stephen Harper, this policy was entrenched when Canada put a full-stop to prosecutions of international crimes in Canadian courts. In fact, since 2013, no case of international crimes committed abroad has been heard in a Canadian courtroom. Instead, the Harper government created a ‘Most Wanted’ list and doubled down on deporting alleged perpetrators. Under this policy, Canada might even send perpetrators back into situations where they could further torment their victims. That perpetrators would be apprehended only to escape justice once deported was a fact that earned Canada a sharp rebuke from the United Nations Committee Against Torture in 2012.

So, if Canada won’t prosecute such figures, will it at least prevent them from getting into the country?

Canada has sophisticated if imperfect measures in place to prevent suspected perpetrators of international crimes from entering the country. It carefully screens migrants coming from war-torn contexts. It also has the fortune of a unique geography. Unlike European states that share a common land mass with areas of the world that have recently experienced mass atrocities and war, Canada is surrounded by three oceans and the United States. Put simply, it is much harder for perpetrators cloaked as migrants to get into Canada. But it does happen. In 2016, the last time the government published numbers on the matter, it was estimated that at least 200 perpetrators of international crimes – war crimes, crimes against humanity, and genocide – were living in the country, often in the knowledge of their victims.

Canada has deported some suspected war criminals. Others continue to live in the country. Under the Trudeau government, Canada has maintained Harper’s policy of seeking to deport alleged war criminals – at times at great cost, and without much success, as one recent case made clear. Both Conservative and Liberal governments have likewise nickel-and-dimed the Justice Department’s War Crimes Program. Its budget has not grown since it was established in 1998 and currently sits at $15.6 million. As some have pointed out, when taking into account inflation, that means the pot of money available to effectively investigate and prosecute war criminals in Canada has actually shrunk.

How can Canada prevent war criminals from arriving on Canadian soil?

The Eldidi case is especially concerning because of the open-source video that allegedly shows him dismembering a prisoner on behalf of the Islamic State. How could Canadian officials miss a video that was posted on the internet, indeed a video that the Islamic State likely wanted people to see? What could Canada have done differently?

The first answer is perhaps the most obvious: properly fund the War Crimes Program so that its staff can effectively investigate, identify, and track individuals suspected of committing atrocities and who may either live in Canada or seek entry into the country. This includes allocating specific funding to investigating international crimes in a manner that would help accountability efforts – and not just deportation proceedings.

Second, Canada should exercise universal jurisdiction and therefore investigate and prosecute alleged war criminals in Canadian courts. The government’s position is that deporting perpetrators (again, without guarantees that suspects will subsequently be held to account) is more cost-effective (i.e. cheap) than prosecuting them. But this policy ignores the fact that prosecuting such figures can deter others from attempting to enter the country. Moreover, the growing acceptance of open-source evidence of atrocities by courts means that the costs of prosecuting perpetrators is diminishing and that some prosecutions may be less resource-intensive than years-long deportation proceedings.

Finally, Canada should commit to opening structural investigations into situations of armed conflict and mass atrocities that create massive refugee flows. Rather than focus on specific individuals or events, a structural investigation seeks to cast a wide net and therefore collect evidence of a wide range of unlawful and criminal activities. Such investigations collect information of international crimes in part by collecting evidence from refugees fleeing violence and entering Canada. Evidence can come in the form of witness testimony, but also photographs or videos stored on their computers and phones.

Investigators can capture, store and preserve that evidence for use in our courts or share it for use in the courts of other states and international tribunals. Such evidence, when used correctly, can also help to determine potential suspects of international crimes who seek entry into the country. It is notable that France, which tipped Canada off to Mr. Eldidi’s alleged plans to commit acts of terrorism in Canada, has a structural investigation into Syria. Indeed, with respect to atrocities in Syria and the Islamic State, many of Canada’s allies opened such investigations. Unfortunately, both Harper and Trudeau refused to do likewise.

A structural investigation could not have guaranteed the identification of the Islamic State video in which Mr. Eldidi allegedly appears. But it would have given Canadian authorities a much better shot at doing so. Why? Because such a probe would have included active engagement between officials from the RCMP and Canadian Border Services Agency with victims and diaspora communities, researchers collecting and analyzing open-source videos and data, and allies who map the potential movements and crimes of Islamic State fighters.

Ottawa will now be familiar with these advantages. In 2022, the government opened its first-ever structural investigation, into the situation in Ukraine. The same conditions were at play for Ukraine as they were with Syria: a conflict with credible allegations of mass atrocities spurring massive flows of refugees and a Canadian immigration program aimed at welcoming those fleeing the violence.

There are other situations where these dynamics exist and where a structural investigation, combined with a commitment to prosecuting suspected perpetrators of atrocities, would help keep Canada safe. The situation in Iran comes to mind. Canada has announced that any “senior official” who served in the Iranian government is now inadmissible to come to Canada. But it is silent on whether it would prosecute any Iranian regime figures responsible for atrocities and human rights violations that are already residing here.

The situation in Afghanistan, where the Taliban has instituted a regime of gender apartheid, is also worthy of a structural investigation. So too is the humanitarian catastrophe in Sudan, recently covered by former Canadian diplomat Nicholas Coghlan.

Late last year, Minister of Justice Arif Virani stated: “I will always support ensuring that people who have perpetrated war crimes… are brought to justice.” That sounds promising, but the status quo of handwashing, avoiding accountability, and finger-pointing appears entrenched in Ottawa. If things remain as they are, Canadians should expect more revelations of Nazis, terrorists, and war criminals living in our midst.

Or maybe the Mr. Eldidi case will bring about introspection and a belated wake-up call. If so, Canada needs to implement concrete policies to properly resource Canadian war crimes investigators, set up structural investigations when the conditions are right, and commit to prosecuting alleged perpetrators in Canadian courts when they do manage to arrive in the country.

********

A version of this article first appeared in Open Canada.

In 2011, the UN Special Tribunal for Lebanon (Appeals Chamber), Interlocutory Decision on the Applicable Law: Terrorism, Conspiracy, Homicide, Perpetration, Cumulative Charging, STL-11-01/I, 16 February 2011, had already recognised peace-time terrorism as a crime, it also indicated that ‘a broader norm that would outlaw terrorist acts during times of armed conflict may also be emerging.’ The generic elements of the offence are suggestive of the definition in the 1999 Terrorist Financing Convention and its Annex (paras 90, 107-109).

The Appeals Chamber foresaw that the generic elements of the offence which are suggestive of the definition in the 1999 Terrorist Financing Convention and its Annex might become customary law definition, in future (para 106).

The 2014 ongoing acts of terrorism, genocide and other atrocity crimes committed upon Yazidi and Christian minorities certainly calls for a revisit upon the thesis that terrorism is a customary international crime based on a widespread accepted and agreed international definition.

Pingback: Free Range Terrorists In Canada | First One Through

Yet another case of a country with politicians and a judiciary with no balls. Regardless of wether this coward Ahmed Fouad Mostafa Eldidi had apparently appeared in a 2015 promotional video by the Islamic State, hacking the limbs off a prisoner with a sword – an act which likely constitutes a war crime.

The debate wether he entered Canada or not should be secondary.The fact that he may be a war criminal should be dealt with regardless of how he entered the country.

Canada should first of all deal with this horrific crime he committed and he should be tried and if convicted he should receive the most severe punishment that he can be given, hopefully the death sentence. If Canadian politicians and the judiciary are serious in protecting the Canadian electorate then they need to act and act now.