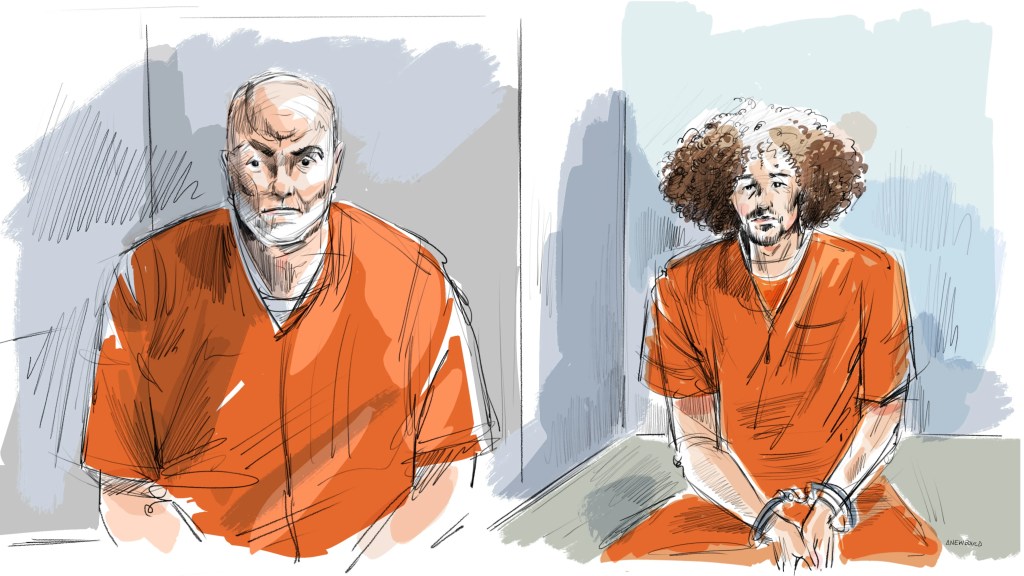

In a major policy reversal, the Canadian government has decided to prosecute an alleged perpetrator of war crimes committed abroad in its own courts. Ahmed Eldidi has been charged by Canadian authorities with multiple war crimes, all relating to his apparent involvement in the torture and killing of an Islamic State detainee in northern Iraq. While questions still loom, this is an opportunity for Canada to do its part in achieving justice for victims of international crimes.

Mr. Eldidi was charged with the war crimes of murder, mutilation, torture, and outrages upon personal dignity under the Crimes Against Humanity and War Crimes Act of 2000. Thanks to the principle of universal jurisdiction, all of these crimes can be prosecuted in Canadian courts – even when they were committed abroad. The allegations stem from an ISIS propaganda film called “Deterring Spies”, which investigators believe shows Mr. Eldidi hacking the hands off a crucified detainee in northern Iraq.

Before the announcement that Mr. Eldidi would be prosecuted, Canada’s last universal jurisdiction case concluded in 2013. As I have explained before, the preference of Conservative and Liberal governments in Canada since then was to deport alleged war criminals out of the country while doing nothing to ensure they would subsequently be held to account. This is true despite the Department of Justice announcing in 2016 that at least 200 perpetrators of international crimes resided in Canada (the Department has since stopped publishing statistics on the topic).

So, what changed?

First, Mr. Eldidi’s alleged crimes were caught on camera. Open-source data is increasingly used in prosecuting war crimes – including by ISIS in countries like Sweden and The Netherlands. Canadian authorities were likely encouraged by the fact that they are not inventing the wheel in using open-source evidence to prosecute war crimes and, critically, that the cost of prosecution would be minimized if the video played a leading role in prosecuting Mr. Eldidi.

Of course, open-source evidence is not enough on its own. Experts will be required to verify the origins and authenticity the film, provide testimony that the person in the ISIS video was in fact Mr. Eldidi, and explain contextual factors, such as how the torture inflicted on the victim in the video could never have been a legitimate or lawful form of punishment or sentence.

Second, Mr. Eldidi was granted citizenship in May 2024 – just months before he and his son were arrested on suspicion of planning a terrorist attack in Toronto. The fact he gained citizenship means that Canada cannot legally deport him.

Third, Canadian officials will have watched the regime of dictator Bashar al-Assad collapse in spectacular fashion. Being serious about prosecuting ISIS figures will bolster Canadian’s otherwise meagre reputation on holding atrocity perpetrators to account. It likewise signals to the Syrian and Iraqi diaspora in Canada that the government believes what they were subjected to atrocity crimes and, when given the opportunity, will act to prosecute them.

Authorities were therefore left with a cost- and evidence-efficient case against someone they couldn’t lawfully deport, and whose prosecution matters to victims affected by ISIS atrocities.

Still, some questions remain.

Canada’s ability to prosecute international crimes in Canadian courts has atrophied. The budget of the war crimes section of the Department of Justice is no higher than when its budget was initially set in 1998. Does the prosecution of Mr. Eldidi signal a genuine renewal of interest in exercising universal jurisdiction? If so, dedicated resources to that end are imperative.

Will the case against Mr. Eldidi set a precedent? Might Canada begin to investigate and prosecute other individuals responsible for international crimes? If so, who might be next? Perhaps some figures associated with Iran’s brutal Islamic Revolutionary Guard who are living in Canada? Or could Canada track Assad’s butchers and torturers who are fleeing the country and who might try to enter Canada? The smart move would be for Canada build expertise and muscle to become a persistent leader in the investigation and prosecution of international crimes.

Will Canada learn the lesson that opening structural investigations – probes into conflicts that do not target specific perpetrators – are indispensable, especially when those situations create massive refugee flows? Unlike its allies, Canada didn’t open one into ISIS or Syria, though it has done so for the war and Russian atrocities committed in Ukraine. Doing so may be a key to preventing alleged offenders from entering Canada in the first place.

Whatever the answers to these questions, it is crucial that the prosecution of Mr. Eldidi not be manipulated for short-term political gain. While they signal care and compassion for victims, such prosecutions must not be exploited for anti-immigration or xenophobic purposes.

The charges against Mr. Eldidi are a drop in the buck of what is needed to address the legion of atrocities committed against Syrian civilians. But his trial represents Canada’s most significant contribution to that effort to date and might even help return Canada to being a productive player when it comes to addressing war crimes, including its own courts.

Pingback: The LOng Shadow Of Dos Erres – waltradecc corporation