Dear readers,

I am pleased to introduce to you Patrick Wegner. Patrick is a PhD student at the University of Tübingen and at the International Research School for Successful Dispute Resolution of the Max-Planck-Institute for Comparative Public Law and International Law in Heidelberg. He writes about the impact of ICC investigations on ongoing conflicts. Patrick has graciously agreed to guest-post at JiC on the nexus of international criminal justice, law and politics. Enjoy!

‘There is little hope for the promotion of the rule of law internationally if the most powerful international body makes it subservient to the rule of political expediency.’ – Former ICTY Chief Prosecutor Louise Arbour

ICC Chief Prosecutor Moreno Ocampo reports to the UN Security Council concerning the investigations in Darfur (Photo: http://wn.com/Sudan_ICC)

Law versus politics in international criminal justice

One of the most contested issues in pursuing justice in conflicts is the question to what extent political calculations play into the decision whether to prosecute or not in a particular case. This question is of special relevance for the work of the International Criminal Court (ICC), as it can not only decide whether or not to prosecute particular individuals, but also whether or not to start investigations in a particular conflict at all. Most people would say that legal and political considerations should be completely divorced when international criminal law is being applied. After all, fairness is a main criterion of justice which can only be guaranteed if the same rules are applied to similar cases irrespective of other considerations. But in international relations it might be difficult to guarantee that.

Unlike on the national level there is no overarching state power that guarantees the prosecution of crimes in the international arena. Whether investigations are initiated and whether they lead to arrests depends to a large part on a couple of powerful states within the international community. These states have their own priorities and interests, and international courts and tribunals are often merely one factor in their overall equation. The policies of these states have an impact on the prosecutions, and international prosecutors have to decide how to arrange themselves with these powers. An obvious example is the ICC’s dependency on its donor countries. Some say this dependency contributes to a selective approach in prosecutions, excluding allies of major donors. This is problematic since powerful states might try to use the ICC and other courts and tribunals as instruments to further their own aims. For example, there have been attempts to use both the International Criminal Tribunal for the former Yugoslavia (ICTY) and the ICC as levers of Western powers to apply political pressure on states like Serbia and Sudan. In the case of the Special Court for Sierra Leone (SCSL) the US is believed to have pressured Liberian President Sirleaf to support the indictment of former President Charles Taylor. While the prosecutors depend on the support of these states, close cooperation might lead to perceptions of a biased and political court, which will in turn have negative repercussions for the investigations. This is the case as the credibility of an international investigation in an ongoing conflict depends on being seen as neutral. If it is seen as a one-sided endeavour, it quickly becomes a contested issue among the parties and thus part of the conflict.

Charles Taylor at his trial in the external facilities of the Special Court For Sierra Leone in The Hague (Photo: AP)

Already there are several authors like Mark Drumbl and Ramesh Thakur who criticise that international criminal law is championed by Western states but applied elsewhere, pointing out the de-facto impunity of the United States. This problem is further exacerbated because decisions to support investigations in conflicts are increasingly motivated by the moral indignation of citizens living in powerful Western states. The global media coverage of crimes committed in conflicts has led to growing demands of civil society groups all over the world to ensure criminal accountability for these crimes. Both in the case of the ICC investigations in Darfur as well as in northern Uganda there are strong domestic civil society movements in the US, pushing their government to intervene on behalf of the victims and to support the ICC.

Civil society movements like Save Darfur mobilise domestic support in the US to call for more interventions in conflicts.

At the same time, the role that Western states play as external actors in mass atrocities is often left out. In this context, some even accuse the ICC of an overall political bias and a partisan application of law by only targeting those countries that are no US allies. Their argument is that the ICC’s dependence on long-term acceptance by the US has led the Court to abstain from indicting US allies like the National Resistance Movement in Uganda or the Kagame Government in Rwanda for its involvement in the conflicts in the eastern parts of the Democratic Republic of Congo (DRC). As a result, Mahmood Mamdani sees the danger of justice being turned into a private good of Western populations. As stated above, a consequence of this is that the moral legitimacy and the neutrality of international courts are doubtful, because they do not always apply norms consistently to all states.

In the case of the ICC this problem is exacerbated by the role the Rome Statute assigns to the UN Security Council. The Council can refer cases, even those located on the territory of non-state parties, to the Court, or defer investigations for 12 months through a renewable resolution. At the same time, the UN Security Council is a politically skewed body due to the veto powers of its permanent members. Three of the five permanent members – the US, Russia and China – have not ratified the Rome Statute but still use all the influence they can muster to shape the agenda of the ICC. For a coherent application of justice principles the involvement of the UN Security Council with its unjust decision making is extremely counterproductive.

Practitioners within the ICC system seem to be aware of the problematic role of the UNSC. When I had the chance to ask the President of the Assembly of the States Parties of the ICC, Ambassador Christian Wenaweser, about the role of the UNSC in referring cases, the Ambassador confirmed that the current setup is problematic. He characterised the UNSC role as an imperfect compromise that is needed as long as the Rome Statute has not been ratified by all existing states. He also stated that UN referrals would remain the exception in future (this was before the Libya referral). When asked about the role of the UN Security Council, staff from the ICC Pre-Trial Chamber answered in a similar way, remarking that they had to live with some bad compromises that have been struck in order to make an adoption of the Rome Statute possible.

This example shows that there are some inherent contradictions in the Rome Statute system that may lead to an uneven application of the law. This uneven application is dangerous for institutions meant to deliver justice, since they can be challenged on the very grounds of justice if they do not deliver it fairly and coherently. As international criminal tribunals are dependent on the support of other states, organisations and the local population, they cannot afford to be challenged by broad constituencies.

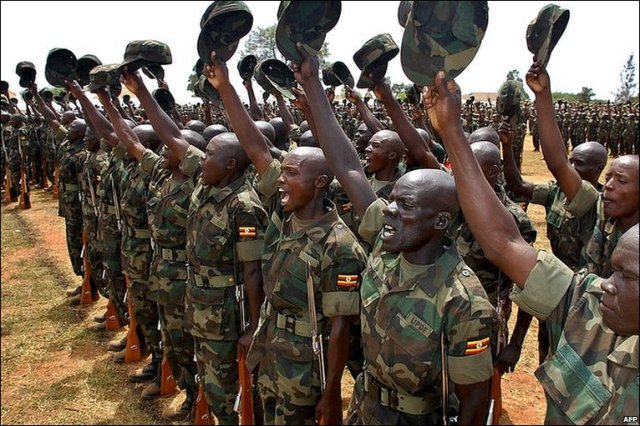

Soldiers of the Uganda People’s Defence Force. Some voices among northern Ugandan civil society accuse the ICC of biased investigations as nobody from the army’s ranks has so far been indicted (Photo: AFP)

Similar problems connected to a selective approach may be encountered on the national level in some cases. As mentioned, international criminal tribunals and courts depend on the cooperation of other actors. This is especially true for the government of the state in which the court or tribunal investigates. The problems confronted by the ICC when trying to investigate crimes committed in Darfur have demonstrated the difficulties of conducting investigation without government cooperation. As a result, there are incentives for courts and tribunals to cooperate with local governments. In some cases, this may lead to a selective approach in the investigations, focusing on the crimes committed by non-state actors and ignoring those committed by the respective armies or government officials. In the case of the Rwandan Patriotic Front (RPF) government in Rwanda, it seems pretty clear that the state has created a justice system that helps to consolidate the regime and in which the International Criminal Tribunal for Rwanda (ICTR) plays an important role. This is partly possible because the most important donor countries of Rwanda have accepted impunity for the war crimes committed by the RPF since the government guarantees stability in Rwanda. Accordingly the ICTR did not receive any international support when it tried to investigate RPF crimes. On the contrary, the joint Office of the Prosecutor of the ICTY and the ICTR was split in order to get rid of Chief Prosecutor Carla del Ponte who had initiated preliminary investigations of RPF crimes in Rwanda.

There have also been claims that the ICC is not investigating government parties in Uganda, the DRC and the Central African Republic in order to ensure the further cooperation of the respective governments in the investigations already under way. To sum up, the current setup of the international system makes it very difficult for international tribunals and courts to pursue justice free of all political considerations. As long as this problem cannot be overcome, international criminal justice will always be branded as political by those indicted. If perceptions of biased investigations gain the upper hand, international criminal justice could even come to be seen as part of the cynical system guaranteeing impunity for the most powerful that advocates of the ICC originally wanted to abolish.

Pingback: The Political Nature of International Criminal Justice « Legal Decisions

The political nature and lack of uniformity in the decision making process at the UNSC defeats the purpose of having the referral system in the first place. I argue that there is a failure of synergy between the two international bodies i.e. ICC and UNSC in my paper (http://works.bepress.com/dchatur/7/)

As much as I hate to say it (me being a lawyers and all), politics competes with law. And in a way, politics is above the law.

The only time law will ever be considered totally free, just and independent of politics is when it is invoked automatically. Therein lies the problem.

I am sure this will not get a reply simply due to how long ago this was posted however in the event somehow it does I was just wondering if you could elaborate on your statement. I am currently writing a research paper for my international conflict course at the University of Georgia and my interest are aligned with the idea that politics in international law in regards to prosecutions and investigations in the international conflict area are more so influential then the actual law.