Unsurprisingly, the international criminal justice blogosphere is abuzz with news of Sudanese President Omar al-Bashir’s visit to Libya (see here, here and here). Bashir, as readers will know, is wanted by the Court for all three charges on the ICC’s menu: crimes against humanity, genocide and war crimes. Libya, of course, came under the jurisdiction of the ICC when the UN Security Council referred the country to the Court.

In Libya, many citizens have expressed anger at the National Transitional Council’s decision to welcome Bashir. Some have gathered in Tripoli to protest Bashir’s visit.

Predictably, human rights groups and defenders of the Court are livid. How, they ask, could Libya let one of the world’s most wanted men come for a visit? There’s a tinge of uncomfortable paternalism in some of the commentary – a bit of “you owe us not to do this” – but more remarkable is the utter silence of Western states towards the visit, apparently leaving news sources with only Human Rights Watch’s Richard Dicker to quote (see here, here and here).

Readers will know my thoughts on the West’s Arab Fling with the ICC in Libya. In my view, the ICC and international criminal justice more broadly, was essentially used and subsequently abandoned by key Western states. Once it became clear that it was better to eliminate Gaddafi than put him in the dock, the principles of international criminal justice were pushed to the wayside. This was always the risk when the UN Security Council, the most political of bodies cozied up to the Court.

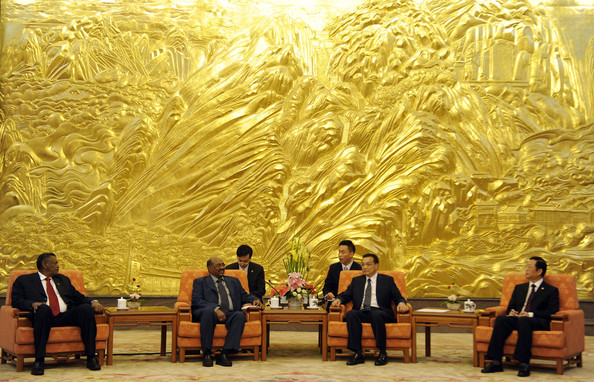

On Bashir's other trips, such as his visit to China, states have been criticized. Why not this time? (Photo: Pool/Getty Images AsiaPac)

Over at The Multilateralist, David Bosco has an interesting take on the Bashir visit and the West’s apparent disinterest:

“Libya will happily endure blistering press releases from the human rights community in order to cement relations with a rich and powerful neighbor. The only thing that would change that equation is the insistence of other powerful states that there would be serious consequences for welcoming the Sudanese president. Bashir’s arrival suggests that message either was not sent–or was not received.”

I agree with Bosco and I don’t think it is particularly controversial to suggest that Libya’s National Transitional Council would have listened if some of the states which had intervened in Libya said: “Look, we don’t want you to let Bashir come to Tripoli. We get that you need to have good relations with Sudan and repay them for their support but we’d prefer if you requested someone else to come in his place and represent him.”

I may be wrong (and correct me if I am), but to date, not a single Western government has commented on Bashir’s visit to Libya. This deafening silence amongst Western states appears to be symptomatic of the trend of abdicating responsibility, and seemingly even interest, in the delivery of justice in Libya. The chorus of criticism may, indeed hopefully, become too loud for Western leaders to ignore. Nevertheless, I predict that some message will be neatly crafted to suggest something to the effect of: “We do not support the visit of Mr. Bashir but Libya, as a sovereign nation free from the clutches of tyranny, is able to decide whom it accepts on its soil.”

When Muammar Gaddafi was killed, US Secretary of State, Hilary Rodham Clinton, famously joked: “We came, we saw, he died.” It was clear then that what mattered for at least some of the key intervening powers was that Gaddafi was gone, not whether justice or the rule of law would be served. Sadly, the silence in Western capitals over Bashir’s visit to Libya only reaffirms this attitude once again.

The ‘deafening silence’ is not for anything else but that Libya has agreed to become a willing mistress for the perverts that lead the West; Obama, Sarkozy and Cameron. As long as the NTC allows access to Libya’s succulent treasures, there won’t be any outcry or outrage least of all from Ocampo, and who takes his cues from NATO headquarters in Brussels, it will more likely be yelps of ecstasy. When many Africans said ICC was a political court whose singular purpose is to intimidate African leaders who dare not cooperate with the reptilian malevolence of Western imperialists, they knew exactly what they were talking about.

One cannot, unfortunately, choose their neighbours. North Africa is a rough neighbourhood. I am entirely sure who will need whom more – Sudan or Libya. Both are sort of failed states, let’s face it. Sudan has recently said farewell to 35% of its former territory (now there’s a new and terrible frontier for human rights, just read about some of the tribal warfare in South Sudan, the newest sovereign state). Libya has deposed one despot and is seemingly eager to replace him with a slightly more accountable but still somewhat repressive government, not to mention their GNP has plummetted and their infrastructure been severely affected by the uprising and warfare of last year. I would wager to say that the Libyans will want to reach out to all the former client states and allies they’d had in Africa – pleasant or not, Gaddafi did have an interesting and novel concept there with pursuing more African unity…too bad about the self-aggrandization that went along with it. – Anyhow, not to get too far off topic, it seems to me that not many African states will arrest Bashir but his physical freedom of movement has been limited. Very logistically difficult to go after a head of state who enjoys some popularity or legitimacy at home. Unless one goes to war (see Iraq).

Unlike the first repondent, I won’t comment on the Western leaders here, they are not relevant to this particular situation. I do share some skepticism about the Western (read: American, British and French) motives for and the actual role in removing the ‘mad colonel’ but it was a good thing, in some symbolical sense at least. Next 10 years will show whether it was a wise and pragmatic move or not.