Paul Bradfield joins JiC for this post on the Ongwen verdict. Paul is an Associate Researcher at the Irish Centre for Human Rights at NUI Galway. He previously worked for the Office of the Prosecutor from 2013-2018. The views expressed here are entirely his own. The piece is part of our ongoing symposium on the life and trials of Dominic Ongwen.

Tragic as it was, Dominic Ongwen’s conviction was correct, both morally and legally. His crimes demanded accountability. As we reflect on the complexities of this case, it’s important that we do so with full reference to the facts of the case. And to those who reject this judgement as legally deficient or morally unjust, we must also ask them to specify what is their alternative – can it really be argued that once someone reaches a certain level of victimhood, that no accountability should be permitted?

From 2012-2013, I had the privilege to live in Gulu, northern Uganda, working on human rights and transitional justice issues. Living among the Acholi people was a defining time in my life. Their decency, humility, and kindness is unparalleled. I saw first-hand how the people of the north were grappling with the legacy of war. Debates around amnesty, accountability, traditional justice and reparations were very contentious then, and continue to be now.

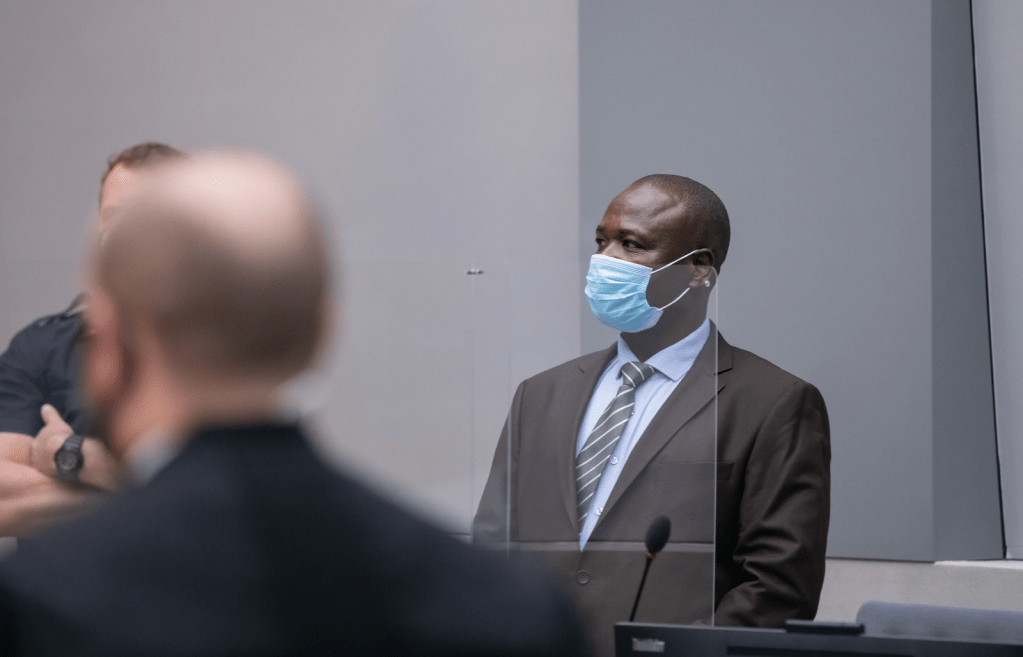

A few years later, I found myself working for the Office of the Prosecutor (OTP) when Dominic Ongwen was unexpectedly surrendered to the court. I worked on the trial for four years until the close of the Prosecution case. Watching the trial judgement was the culmination of years of dedicated work by many people. A large team of lawyers, investigators, witness support, IT staff, translators, transcribers, security, drivers and others all deserve recognition for bringing justice to thousands of participating victims.

Since Ongwen was apprehended, his own victim status has been a central feature of the case. His prosecution went against the grain of mass amnesty on the ground. Over 13,000 ex-LRA rebels have received amnesty since 2000. In Uganda, opinions are understandably mixed. My recent PhD fieldwork also bore this out, with ex-LRA rebels that I met essentially divided on whether he should be prosecuted or not. Diverging views were also evident in the communities I visited.

Ongwen’s abduction was tragic. This was readily acknowledged in the OTP’s opening statement (at p.35). However, Ongwen was on trial for things he did as an adult, with significant authority and independence as a Brigade Commander. He was no Kapo. He had the chance to walk away from the horror of his crimes, but made a conscious choice to stay in his position of power. At a notable encounter with the UPDF, religious leaders and others during peace talks, he was offered the chance to defect and allow his child soldiers their freedom, but he refused (at p.83).

I was often intrigued by some of the commentary around the case, and now the judgement. There is a certain degree of cognitive dissonance apparent within it. Philosophical or legal examination of difficult cases such as Ongwen’s should not merely be emotional, abstract exercises. It must be grounded in a full canvassing of all the relevant facts, the arguments of the parties, the applicable procedures, and most importantly of all: the evidence.

For example, if you read academic journal articles on the Ongwen case, you will find there is a near-complete absence of detailed discussion or analysis of the actual evidence – the allegations, the crimes, the witness testimony, or what Ongwen is actually accused of doing. His actions are too easily brushed over. When interrogating the victim-perpetrator dilemma in this case, it is necessary to examine both aspects in detail.

In an attempt to address this gap, I wrote a paper on the sexual and gender-based crimes that Ongwen is accused of personally committing. If you have any doubt as to the moral propriety of this trial or its outcome, I invite you to read the testimony of these seven women, who were forcibly married, raped, forcibly impregnated and sexually enslaved by Dominic Ongwen (see pp.738-771 of the judgement). I have worked at three international courts on six different cases (four of these as a defence lawyer), and I can say without hesitation that the testimony from these women was the most harrowing I have ever heard.

Commentary on the case also seems unaware of some important points. In its closing brief, the Ongwen Defence actually reject the victim-perpetrator label, submitting that he is a victim only (at para.20). Indeed, all responsibility was denied. For example, the finger of responsibility for charged attacks on IDP camps was pointed elsewhere, at other LRA commanders. The “grey zone” – so often referred to in victim-perpetrator discourse and in this case – was deemed not applicable to Ongwen. Thus, the “reductionist binary” of either victim or perpetrator – which this trial judgement has been accused of reinforcing – was actually preferred by the Defence.

The denial of all responsibility by Ongwen also undermines the argument that Ongwen should instead undergo some form of traditional justice, such as mato oput. In the final paragraph of its closing brief, the Ongwen Defence creatively asked the court that in the event he is found guilty, Ongwen should “be placed under the authority of the Acholi justice system to undergo the Mato Oput process of Accountability and Reconciliation as the final sentence for the crimes for which he is convicted.” (at para.773)

However, this cultural ceremony requires an admission of responsibility, an apology to the victims’ family and the offering of compensation (at p.54). None of these ingredients are present in the Ongwen case so far. This is not to say Ongwen should have waived his right to silence – no, that is inviolable. It is simply to point out the incongruity. An unsworn statement at the end of trial, as other accused persons have made, could have begun to signal some degree of remorse, if mato oput is what is really desired.

Another argument regularly made by commentators is that the trial process did not allow for the complexities of Ongwen’s life to be revealed and examined. This belies the true nature of the trial proceedings. By advancing defences of mental disease and duress, and calling witnesses in support of them, Ongwen’s lawyers had significant scope to shape the narrative of the trial. For example, Defence witnesses testified at length about the role of spiritualism in the LRA and Acholi culture generally. Others testified about the circumstances of Ongwen’s abduction and the brutal process of LRA indoctrination. Defence medical experts also testified for days about Ongwen’s mental health. All of this testimony is considered and analysed at length in the trial judgement.

Criticisms of the judgement for not addressing Ongwen’s victimhood in more detail are somewhat hasty, and seem to misapprehend the court’s procedure. Under article 74 of the Rome Statute, the judges must first decide on criminal responsibility. It is only once that has been established, does the process move to the sentencing phase under article 76. Under this latter provision, the Trial Chamber will “consider the appropriate sentence to be imposed and shall take into account the evidence presented and submissions made during the trial that are relevant to the sentence.” During this next phase, which has been scheduled for mid-April, the parties may call additional witnesses to testify and make further submissions.

The sentencing decision that will follow will no doubt extensively engage with the mitigating circumstances that are clearly present in this case. When deciding on an appropriate sentence, Rule 145 requires the judges to take into account mitigating circumstances and the background of the convicted person, including their age, education, social and economic condition. We should resist the temptation to condemn the Trial Chamber before this process has been completed.

Indeed, there are potentially innovative options open to the judges. Inspiration may be drawn from the statute of the Special Court for Sierra Leone which, although never utilised, included progressively restorative sanctions for child soldiers that placed emphasis on their rehabilitation (see article 7). For example, should Ongwen serve his sentence in Uganda, he could be given interim release to perform a traditional ceremony, before completing his sentence. There is no reason why Ongwen’s sentence cannot allow for restorative aspects to be incorporated within it.

It should be recalled that both Ugandan domestic law and Acholi cultural practices emphasise accountability for wrongdoing. Victim-perpetrators are held accountable every day in courts around the world, including in Uganda. Another LRA victim-perpetrator with a similar background to Ongwen and accused of similar international crimes, Thomas Kwoyelo, is currently on trial in the Ugandan High Court.

Ultimately, Ongwen’s tragic victimhood was always that: mitigation. It could never have reasonably amounted to an excuse to victimise others – to the point of committing crimes against humanity – without any culpability. Those who label this trial as unfair or deficient in some respect, have, in my view, never convincingly confronted this. It is also hard to discern from those same criticisms what the alternative should be, as no details or proposals are offered beyond simply labelling this trial as complex, inadequate and tragic.

That the ICC has decided to hold a former child soldier accountable for committing serious crimes as an adult may be uncomfortable and hard to digest. That’s because it is. But the ultimate sentence can still be a sensitive and holistic one.

In the present case, and given the evidence before it, holding Ongwen accountable was the legally and morally correct thing to do.

Pingback: Ongwen blog symposium: Two Sides of the Same Coin: The ‘child soldier experience’ at the ICC | Armed Groups and International Law