The following contribution to JiC’s ongoing symposium on Informers Up Close comes from Patryk I. Labuda. Patryk is an assistant professor of international law and international relations at Central European University in Vienna and a researcher on the ‘Memocracy’ project at the Polish Academy of Sciences, Institute of Law Studies in Warsaw. For all other contributions to the symposium, please see here.

Mark Drumbl and Barbora Holá’s new book ‘Informers Up Close’ is a beautifully written, riveting read and first-rate scholarship. Drawing on the case study of Czechoslovakia during communism, the authors open up the ‘black box’ of collaboration to offer a nuanced, multi-level, and emotionally informed analysis of the informer – whom they define as “a common citizen who gathers and then supplies information, usually clandestinely, to authorities”. In this post, I offer some thoughts on the book’s path-breaking analysis of Czechoslovak informers, its innovative proposals for how to think about informing in transitional justice processes, and then turn to a few broader comparative riddles and epistemological challenges arising from the Eastern European context.

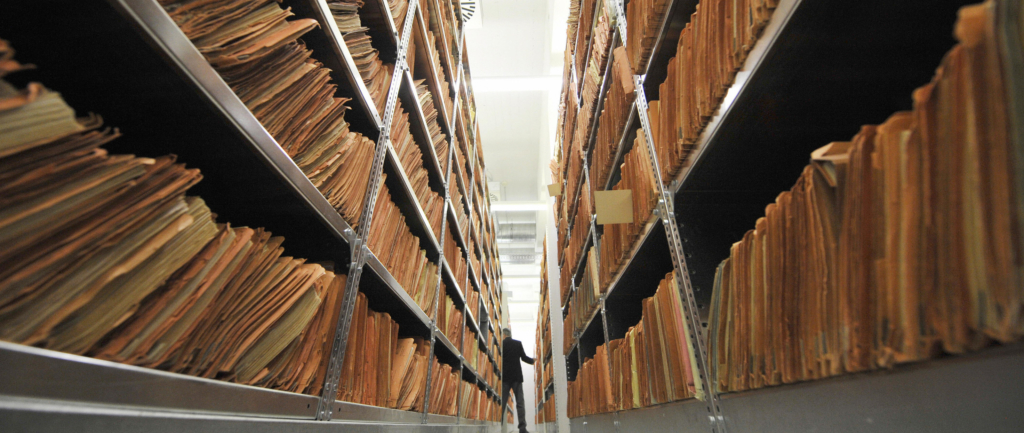

One of the book’s major contributions to the literature is its deep dive into the Czechoslovak archives. Building on oral histories and secondary scholarship, Drumbl and Holá examine hundreds of secret police files to extract and analyse “the emotions that drive and animate… informing and talking to the secret police”. The book identifies and unpacks four main emotions as drivers of informing – fear, desire, resentment, and devotion. However, the authors recognize that these are not airtight categories, that other emotions may also explain certain behaviours, and that an emotional analysis of informing is ultimately a methodological choice (but not the only research lens into informing).

Chapter 4’s careful, rich and vivid reconstruction of six informers captivates and immerses the reader into a distant world whose written and unwritten rules we try to understand as best we can, while guiding us through ordinary and less ordinary lives where informing played different roles – from mundane gossip about neighbours to denunciations that harmed people. Lily’s tragic story (and unknown fate) sits uneasily alongside Golfus’ complicated and inglorious personality or Soukup’s messy life ‘choices’. (I am aware, and embrace, that the order of ‘memorable’ characters and the emotional adjectives used to describe their stories may reveal something about my own positionality vis-à-vis this book). Ultimately, the six files – and several more in an online annex – are meant to do two things: first; help readers to think through why informers worked with the secret police in a repressive regime like communist Czechoslovakia; and second, a “‘high-resolution portrayal’ of informers aims to unsettle ‘assumptions of the homogeneity of secret collaborators that underpin the lustration and similar laws” (quoting Roman David).

The Czechoslovak (Czech after Slovakia’s independence in 1992/3) lustration programme brings us to another big theme of the book, namely how transitional justice should deal with informers after the collapse of repressive regimes. Critical of the Czechoslovak experiment with lustration, which was far “more comprehensive and sweeping” than elsewhere in the former Soviet bloc, Drumbl and Holá aim to “[push] back against the political tendency to scapegoat and ostracize informers” and hope instead to “advance more sophisticated and inclusive transitional approaches to rectify the pain that informers simultaneously endure and cause for many others”. Defying the conventional (negative) wisdom ascribed to snitches, rats, moles, and various other derogatory terms that all languages reserve for this class of individuals, the book urges us to view infomers as occupying a liminal space between perpetrators and victims, or – in their words – “tragic victims who victimize”. By excavating the multiple factors that drove Czechoslovak informers, we indeed end up viewing and evaluating (most of) the book’s protagonists in a more holistic and empathetic manner, while reflecting more critically about their roles under communism.

Whereas the Czechoslovak lustration process involved unauthorized ‘wild’ disclosures and public shaming of informers, complemented by state-sanctioned bans from public positions based merely on the listing of people’s names in secret police files, Drumbl and Holá advocate for a six-pronged heuristic framework to guide transitional justice vis-à-vis informers in the future: (i) how much harm did the informing do or could have done?; (ii) what degree of pressure was an individual put under to inform?; (iii) how long did informing happen?; (iv) what motivation drove the informer?; (v) what kind of information was divulged?; (vi) did the informer even know they were informing to the secret police? All six factors speak to important aspects of informing, but the fourth criterion’s link to ideological factors (in particular, a person’s support for or opposition to political ideologies like communism, fascism, (il)liberalism etc.) is central. Yet it is also, inescapably, the most contentious in the context of transitional justice’s inherently political processes (whether the discipline needs a broader approach has long been suggested, recently here, but it remains true that transitional justice still focuses on political transitions away from repressive regimes and/or toward democracy).

This last observation about the politics of informing brings me to several questions, riddles and challenges that I am left with after reading the book. In their chapter on ‘transitional takeaways’, Drumbl and Holá explain that they are pushing back against the excessive simplification, distortion and scapegoating that characterized Czech(oslovak) transitional justice, in particular its implementation of lustration. Instead, they “argue for an aetiological expressivist function of transitional justice, namely to tell it as it was”. The book brims with nuance, but I am not sure how to interpret this particular argument, which reminds me of Ranke’s famous aspiration to history ‘wie es eigentlich gewesen’.

I am of course not suggesting Drumbl or Holá aim, or think it is remotely possible, to reconstruct some positivist and objectively verifiable version of informing. However, their formulation and subsequent analysis did make me wonder if they ultimately underestimate to what extent their (necessary) corrective to the official, distorted version of Czechoslovak informing remains open to political and ideological contestation within inherently mobile, recursive, longue durée transitional processes. Long story short, I agree with Drumbl and Holá’s critique that the Czech lustration process was a shambles, and I laud their proposals for disaggregating the causes of informing. However, I may be less optimistic than they are in that the secret police archives, whose distortions and fragmentary nature in the Czech context (40% of the files were destroyed), could ever provide definitive factual answers – some form of ‘as it was’ – that can, in turn, be walled off from the wider political transition away from repressive rule.

This brings me to another point. At various points in the book, Drumbl and Holá argue that the Czech lustration process was unnecessarily punitive or condemnatory, and insufficiently restorative or geared to reconciliation. I confess I still struggle to fully grasp the meaning and implications of this argument. Unlike transitional justice experiments in other parts of the world, Eastern European states’ reckoning with communism is famous for avoiding criminal justice rather than embracing (mass) trials against the former regime. The Czech Republic is no different. As Drumbl and Holá explain:

…despite investigations, very few criminal trials took place. Still, the transitional process proved rather retributive when it came to informers. Czech transitional justice cast informers as dangerous loyalists and stigmatized them instead of pursuing reconciliatory goals.

This argument runs through the entire book, but I am unsure whether the problem for Drumbl and Holá is the punitive nature and ineffectiveness of lustration as a transitional justice tool per se, or rather the undifferentiated and condemnatory way in which Czechlustration, unauthorized disclosures, and access to the archives were mis-handled. While I agree with Drumbl and Holá if their concern is how transitional justice was implemented (and the book convincingly demonstrates its many flaws vis-à-vis informers) in the Czech context, I am less sure that a pivot toward ‘reconciliation’ can solve the wider dilemmas of transitional justice. It would be too much to suggest they should have written an alternative history of Czech transitional justice, but it remains true that Drumbl and Holá never really explore what reconciliation with different classes of informers could or should look like.

In the Czech context (or other transitional societies), whom specifically would we be reconciling with which informers and – equally important (a point I return to below) – to what transitional end? In countries that have adopted more conciliatory approaches to the past, most notably South Africa, the transition is famously critiqued for being ‘too lenient’ toward the former apartheid regime. I agree with Drumbl and Holá’s intuition that transitional justice has generally become more (too?) retributive in the last thirty years, but I wonder also if the aporia of transitions being ‘too condemnatory’ or ‘too conciliatory’ is not some version of the grass always being greener on the other side. In other words, if only the alternative had been tried, the worst excesses or greatest shortcomings of what actually happened could have been avoided? But is it not also possible that today we would be reading (and writing!) a different book about the failures of Czechia’s non-reckoning with informers-cum-unfinished break with its communist past?

The last two questions bring me to the most fraught dimension of (Czech) transitional justice, which is its politics, the politics of (transitional justice) scholarship, and (Eastern) Europe’s memory wars (which I study as part of the ‘Memocracy’ project, with a focus on the global dimensions of memory). In 2022, Russia banned comparisons between the Soviet Union and Nazi Germany. Meanwhile, the 23rd of August, the day of the Ribbentrop-Molotov pact between Nazi Germany and the Soviet Union that launched the Second World War, is now commemorated annually in the rest of Europe – at the urging of post-communist Eastern European states – to honor equally the victims of Nazism and Stalinism. In raising questions about the way in which the post-communist Czech political establishment mis-handled informers and how that relates to dominant post-transition narratives, Drumbl and Holá are careful to emphasize (correctly so) that theirs is a study of Czech transitional justice, which should not be mechanically generalized or extrapolated to other cases – even within communist Eastern Europe (where e.g., Czech communism is not the same as the Soviet Union’s occupation of Baltic states).

Yet in a field like transitional justice, it is difficult to avoid – as they acknowledge – comparisons altogether, which lies at the heart of their tentative theory of ‘just’ and ‘unjust’ informing in chapter 7. I found these comparative sections thought-provoking, nuanced and intense. At the same time, the comparative analysis is embedded within a particular mnemonic register, which left me wondering how the book might read if it had not been a study of (nominally) left-wing repression – for instance, how would one analyze informers in colonial Cambodia or fascist Italy? – which might in turn reflect dominant modes of intellectual inquiry and academic knowledge production thirty years after the fall of the latest left-wing utopia.

I make this last observation because I think this book, which overflows with insights and takes the reader on an intellectual journey with varied and often unexpected turns, is a necessary read for Eastern Europeans, who will benefit from exploring the complexities and nuances of informing under communist rule (contra the work of some memory institutes in the region today). At the same time, I harbour some ambivalence and concerns that, almost three years into Russia’s full-scale aggression against Ukraine, its arguments about the liminality of informing in communist Czechoslovakia, and the politics of the flawed Czech post-communist transition, might actually be mis-understood in parts of the world that mis-interpret Russia as an anti-imperial, emancipatory successor to the ‘anti-colonial’ Soviet Union – despite all evidence to the contrary, as adduced with nuance in this stunning book and as seen daily on the battlefields of Ukraine.