The following is a guest post by Thomas Obel Hansen and Felix Vacas Fernández. Felix is an Assistant Professor in Public International Law and International Relations at the Universidad Carlos III de Madrid (Spain). Thomas is the Maria Zambrano 2023-24 Distinguished Researcher with the Universidad Carlos III de Madrid (Spain) and a Senior Lecturer in Law with Ulster University Law School/ Transitional Justice Institute (UK).

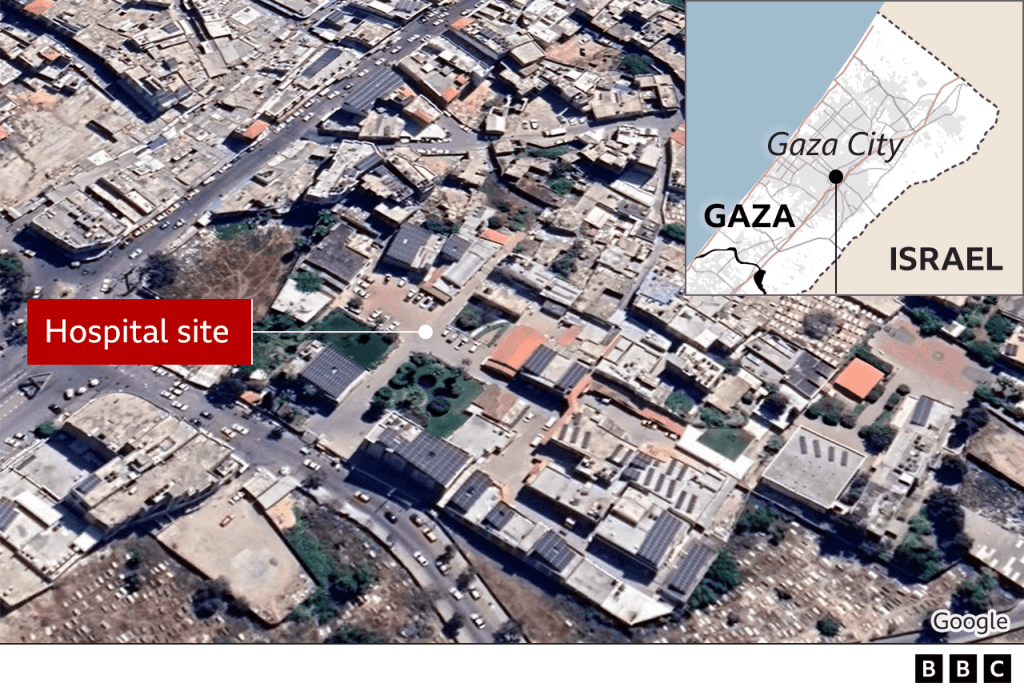

Three months into Israel’s military campaign in Gaza, public debate remains mainly focused on the daily disaster that this campaign has brought with it. In a way, that’s understandable because of the large-scale and systematic targeting of civilians and civilian infrastructure associated with a military campaign unparalleled in contemporary times both in intensity and level of disregard for international law.

However, focusing primarily on the immediate violations and the suffering that comes with Israel’s actions runs the risk of distracting from lasting disaster of the potential ethnic cleansing of the Palestinian population in Gaza. In other words, the daily indiscriminate killing and pulverization of Gaza, as awful as it is, risks being the very means of achieving a more lasting objective consisting in ethnic cleansing, which in its own nature could amount to the crime against humanity of forcible transfer of the population, a crime set out in Article 7(1)(d) of the Rome Statute of the International Criminal Court (ICC).

The general failure of many to ‘see’ this crime unfolding before our eyes and understanding its full implications arguably has to do with how Western governments and media have generally sought to portray Israel’s campaign as ‘a hunt for Hamas’, a type of anti-terror campaign all too familiar in Western capitals. As countries in the West are now strongly encouraging Israel to take a more measured approach, public attention in the West is mainly focused on the methods – not the broader aims – of Israel’s military campaign in Gaza. When criticism has been levied by Western governments, it is on the manner in which Israel is conducting its military operations, not why it is doing so.

But one only needs to listen to what a litany of Israeli leaders say to understand that the overarching objective of the action taken is to fully destroy and empty Gaza of Palestinian citizens. What is being pursued involves the de-population of Gaza, and by extension an expansion of Israeli territory – or at least the areas under its control.

Together with the ongoing expansion of settlements and the massive increase in settler violence in the West Bank, the ethnic cleansing ongoing in Gaza could amount to the completion of the Nakba involving the permanent displacement of the Palestine population out of Palestinian territories. If that happens, countries with the power to do so who failed to stop Israel would be liable, at least in moral and political terms and possibly also in legal terms through notions of complicity.

Continue reading