The following is an interview, conducted by Shehzad Charania, with O-Gon Kwon, former Judge of the International Criminal Tribunal for the Former Yugoslavia and President of the ICC Assembly of States Parties (ASP). For Shehzad’s other interviews with prominent figures in international criminal law, see here.

Last month, I spoke with former Judge of the International Criminal Tribunal for the Former Yugoslavia and President of the ASP Judge O-Gon Kwon. We discussed his career as an international judge and the challenges of being ASP President.

I begin by asking him about his journey to the ICTY. Kwon served as a Judge for 22 years in South Korea but says he couldn’t turn down the chance to adjudicate on behalf of the international community over the most serious crimes. He refers to his election as “pure luck” because of how competitive the process was, and how States tended to favour continuity and therefore the re-election of incumbents. He recalls that the Malaysian incumbent Judge Lal Chand Vohra had decided not to stand again, which he suggests – rather modestly – helped his own chances. “Perhaps I wouldn’t have won if he had stood,” he says. He says his experience as a judge in South Korea was also important, noting that States generally prefer electing practitioners over scholars or diplomat lawyers

Kwon was immediately thrust into action when he was assigned to the case of former Serbian President Slobodan Milosevic. He remembers vividly how “excited” he was on the day of the opening of the case that the entire world was following, and also how shocked he was when he heard the news of Milosevic’s death on a Saturday morning some four years later. At that point, Kwon considered returning home, but felt he had “unfinished business”. He had also been re-elected a year before Milosevic’s death, the ICTY Judges’ terms being only four years. He says that it was “kind of funny” that he had to campaign for his re-election in the middle of such an important case.

His second case was Popovic et al, the largest case at the time regarding the events of Srebrenica, and the first case at the ICTY to deal with conspiracy to commit genocide. Once again, following the end of the oral proceedings, Kwon considered a return to South Korea, in the knowledge that he would be given a higher judicial role there. But then the President of the Tribunal asked him to preside in the case of Radovan Karadzic who had just been transferred to The Hague. It was a challenge he couldn’t turn down. But it was also the busiest period of his career; as he began the proceedings in Karadzic, he was still writing the judgment in Popovic et al.

During his 15 years as a Judge at the ICTY, Kwon also sat in the Appeals Chamber in the case of Strugar and was involved in a number of pre-trial and contempt of court cases. “At one point, I had the heaviest caseload of any of the Judges.”

Kwon did not come to The Hague as an expert in international criminal law but that was not the biggest challenge. “The novelty of the issues and the procedural law we had to devise were among the most interesting experiences. As an international tribunal, we were a hybrid system which incorporated both common law and civil law. We had no precedent to work from. The procedures we established were a response to the issues as they arose, and the lessons we learned. Through this experience I was able to learn about different legal systems and practices very quickly.”

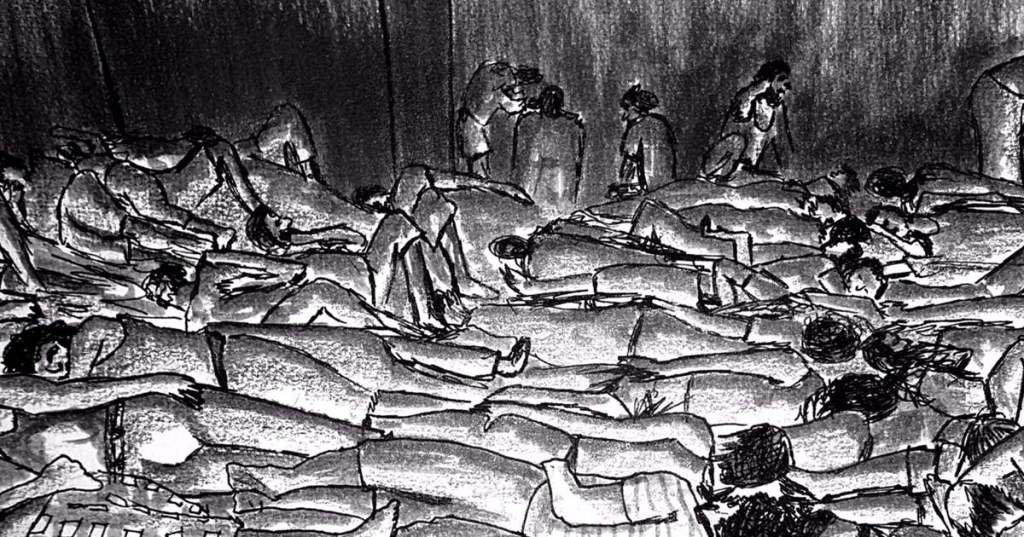

We reflect on the Karadzic case, one of the most high-profile in international criminal justice since Nuremberg. “All three of my big cases had a Srebrenica component. So, I was able to view events there in a really comprehensive way. The Popovic case was exclusively related to Srebrenica; the first time a defendant was convicted of genocide. Karadzic was the highest ranking official and was prosecuted for two counts of genocide – in Srebrenica and the local municipalities. We convicted him for the former and not the latter. We therefore had to be especially meticulous in our reasoning on how we as a Chamber arrived at our finding on genocidal intent.”

Continue reading