The following is the final contribution to our ongoing symposium on Mark Drumbl and Barbora Holá’s new book Informers up Close. It was written by Cynthia Horne, a Professor Political Science at Western Washington University. To see all of the other submissions to the symposium, click here.

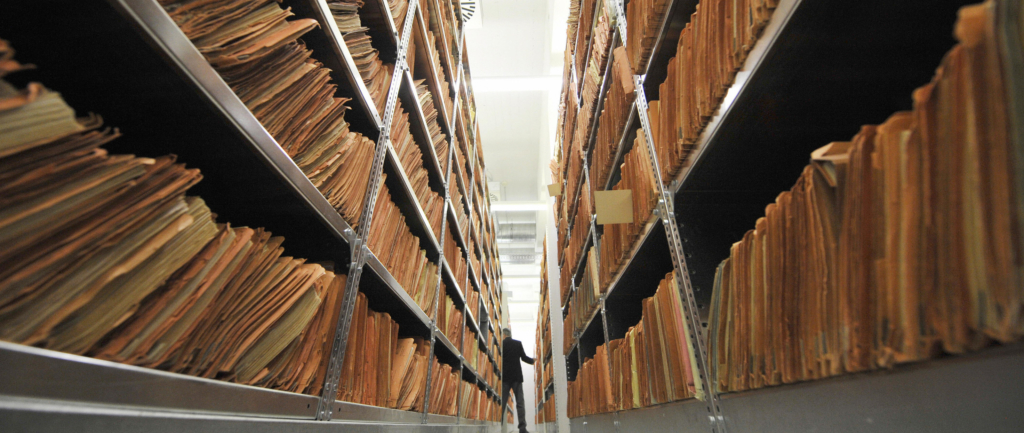

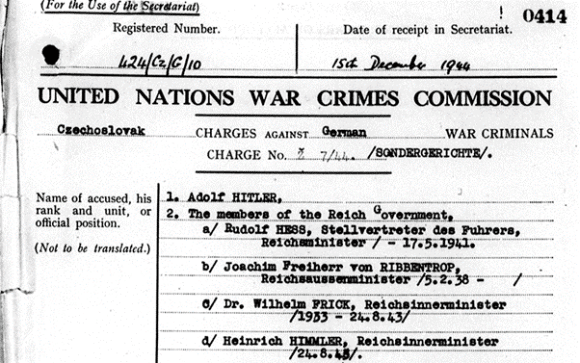

Lustration was a particular form of vetting used in most post-communist transitional justice programs. Although lustration differed by national context, at its most basic, individuals were screened for evidence of employment in or collaboration with the secret police and/or high-ranking communist party membership drawing on information found in the secret police files. Evidence of collaboration could negate eligibility for public office or employment in a range of public and semi-public positions. In some cases this evidence was also publicly disclosed, with the intention of shaming individuals to recuse themselves from consideration for positions.

A core goal of lustration was (re)building trust. This was an acute issue in post-communist countries, which suffered from especially high levels of both social and political distrust. The Vice Minister of the Interior of the Czech situated the lustration of informers within this trust-building context:

The network of [secret police] collaborators is like a cancer inside Czechoslovak society. Is it so difficult to understand that people want to know who the former agents and informers are? This is not an issue of vengeance, nor of passing judgments. This is simply a question of trusting our fellow citizens who write newspapers, enact laws and govern our country.

How was lustration supposed to support trust-building? First, removing those with a past tainted by collaboration was alleged to improve citizens’ trust in the capacity and integrity of public institutions. Second, the threat of revelation was expected to prompt the recusal of collaborators from public office, catalyzing bureaucratic change. Third, the process of revealing the files and acknowledging collaboration was intended to support “the purification of state organizations from their sins under the communist regimes.” In essence, a combination of personnel changes and changes in the ‘moral culture’ of citizens was expected to build trust in the state and public institutions.

Interpersonal trust was expected to change, although how was not entirely clear at the start of the transitions from communism to democratic governance. Finding out that your neighbors, co-workers and family members were spying on you could break any remaining social trust networks. Alternatively, although painful, revealing the scope of the spy networks might help society confront its own complicity in past harms.

Continue reading