One of the few realities of violent political conflicts across contexts is that fully “good” options are in rare supply.

In a recent post, I attempted to articulate some of the tensions surrounding the pursuit of justice in Libya, on the one hand, and the pursuit of a political settlement to the current crisis, on the other. The point was not to articulate some solution to the problems of pursuing accountability and peace simultaneously but to suggest the relationship between peace and justice is far more murky than typically presumed. Nevertheless, a few people have disagreed with my assessment, particularly the notion that a power-sharing agreement is a possibility in Libya.

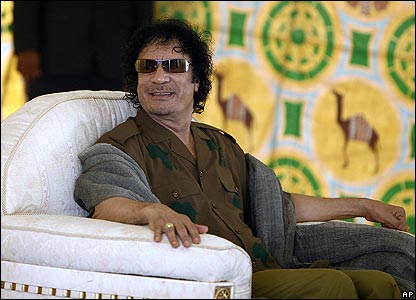

Power-sharing is an option in Libya. Acknowledging the fact says nothing about whether it is an appropriate or good option, but merely the fact that it is an option. Clearly, the African Union (AU) agreed with this assessment when they proposed a peace plan for Libya. The rebels, notably, have not rejected the possibility of a power-sharing agreement but only rejected one between them and Colonel Gaddafi or any of his sons.

The choices that exist for Libya are murky. This post is an attempt to bring some clarity about the options available. Importantly, keep in mind that they are not in order of suitability or preference.

Option A: A power-sharing between Gaddafi or one of Gaddafi’s sons and the rebels.

This option is very unlikely for a number of reasons. First of all, the international coalition has emphatically declared that Gaddafi cannot be part of any government and that he must face justice. The international community, would also likely have to commit to monitoring any such agreement for the forseeable future. Secondly, the rebels have already rejected a power-sharing agreement that would include any Gaddafi. Thirdly, given Gaddafi’s track record, there is little reason to trust that he would be sincere in implementing a power-sharing peace agreement rather than, for example, taking the time to re-arm. Fourthly, as Doug Saunders pointed out to me and as Christine Cheng cogently argues, a power-sharing agreement with Gaddafi risks turning Libya into another Zimbabwe:

“In Libya, any power-sharing deal will likely see Gaddafi’s supporters retain de facto control over the military and the police, while rebel leaders will be given cabinet positions with little actual influence over how the country is governed.

Zimbabwe’s experience suggests that if a leader is so desperate to cling to power that he is willing to use lethal force on opposition members, then power-sharing is unlikely to lead to true democratic reforms.

Indeed, the failure of power-sharing in Zimbabwe should not be surprising. Having led the country for 28 years, Mugabe clearly had the upper hand. Gaddafi, having ruled for nearly 42 years, wields just as much influence, if not more. Consequently, the rebels know that as soon as the international spotlight shifts away from Libya, Gaddafi will quietly re-cement control over security forces and gradually eliminate key political opponents.”

There are concerns by some observers that a power-sharing agreement in Libya could result in a similar situation as in Zimbabwe (Photo: Getty Images)

Option B: Negotiate the exile/asylum of Gaddafi and family + Power-sharing between rebels and pro-Gaddafi forces

It has come to light that various actors, including the US and the AU, have been looking for states to accept Gaddafi and offer him exile or asylum. It remains unclear, however, whether Gaddafi would, in fact, accept such a deal. He has said on many occasions that he will stay in Libya until the day he dies.

Importantly, as noted above, the rebels did not reject the idea of a power-sharing agreement. When they rejected the peace plan negotiated by the AU, their response was:

“The African Union initiative does not include the departure of Gaddafi and his sons from the Libyan political scene; therefore it is outdated”

This appears to leave open the possibility of accepting a power-sharing agreement with individuals loyal to Gaddafi. However, it remains unclear what the strength of pro-Gaddafi factions are in Libya. One commentator suggests that “There is really only one side in this conflict, as far as the general population of Libya – and that is the Libyan people.”

Of course, this option is problematic in that it constitutes a violation of the principles of international criminal justice. If the International Criminal Court issues arrest warrants for Gaddafi and/or his sons, there will be expectations and widespread demands that he is detained and delivered to the Hague.

Option C: Declare Gaddafi a legitimate military target.

In other words, Gaddafi could be targeted by military forces and killed. Morally and legally this seems a questionable approach. There is also an understandable resistance by actors in the international community to be seen to enforce regime change militarily.

Option D: Put “boots on the ground” and take over Libya

The EU is awaiting UN approval to send in a contingent of troops to Misrata. France, Italy and Britain are set to send small contingents to Libya to advise the rebels. While they would not have a combat role, there is something to say about slippery slopes.

Proponents of this option would probably hope that all it takes for peace and democracy to be established in Libya is for international forces to “free” the country of pro-Gaddafi forces. Take control of or occupy the country and all Libyans will flock, given the chance, to the rebel side.

The international community is already mired in problems over credible-commitments in the areas in which it engages. The commitment to putting troops on the ground and “guiding” Libya towards peace would have to be massive. A number of states are clearly hesitant to commit. With two active theaters in Afghanistan and Iraq, US participation would be doubtful. But the extent of the credible commitment would have to be even greater considering how long Gaddafi has been in power.

The temporal issues of engagement remain unclear. While some observers are critical of not engaging/committing sufficiently, for others, military interventions should only be temporary. For the latter critics, the ever-present problem and the lesson of Afghanistan and Iraq is that a “temporary” occupation or military engagement may quickly lose its temporary status.

Option E: Special forces mission secretly detains Gaddafi and family and subsequently brings them to the Hague; precedent problem.

It is questionable how much this approach would help the situation. It is possible that, without being part of a larger mission, it would create a dangerous vacuum. It is not clear who would replace Gaddafi and whether or not that individual would be more or less amenable to peace.

Further, it is unfathomable that any states would want to set this as a precedent.

Option F: Continue as now with no-fly zone and support for rebels

The hope here would be that at some point there will be a major breakthrough on the part of the rebels. That was the general hope when the conflict began. As the Economist describes:

“For a time, it looked as if a pattern had been established. Allied air power would take out the government’s tanks, artillery and other heavy weapons, shell-shocked loyalist soldiers would flee and the ragtag army of rebels toting AK-47s and captured RPGs would surge forward into the vacuum, driving hell-for-leather to the next town along the coast road in a motley cavalcade of elderly cars and pickup trucks…In fact, the only emerging pattern is one of wildly see-sawing fortunes, as coastal towns change hands with almost metronomic regularity.”

Those who support continuing with the mission as it is now will also retain the hope that continued NATO bombing will force Gaddafi’s hand and he or those close to him will give him up.

The risk of keeping with the status-quo approach, of course is a long, drawn-out conflict. Further, if there isn’t a victory in the end, but instead a military stalemate is reached, there would be a need to return to one of the options above and roll the dice again.

Option G: Withdraw all external support.

I don’t think it needs explaining why this wouldn’t be a good choice. Still, it is an option.

****************************

Hopefully the options articulated above add some clarity rather than promulgate confusion. Please do suggest other possible options you may come up with.

None of the above options are perfect. Their consequences aren’t entirely clear. But then again, that is the nature of war.

Excellent breakdown. Thank you for writing it. How about partition? Either de facto or de jure? Possibly involving a Berlin Wall or Israeli Security Fence style barrier? Not advocating this necessarily, but it strikes me as a possible option.

Thanks very much Rob – I am a new reader to your blog as well and enjoying it!

Thanks for highlighting this issue.

Territorial partition has no doubt played a role in establishing peace in some situations, most recently between North and South Sudan. In the variety of claims in civil wars, control of territory is no doubt one that is often expressed, but I haven’t yet heard that it is a desire of the rebels in Libya or a possible option being bandied about by pro-Gaddafi forces.