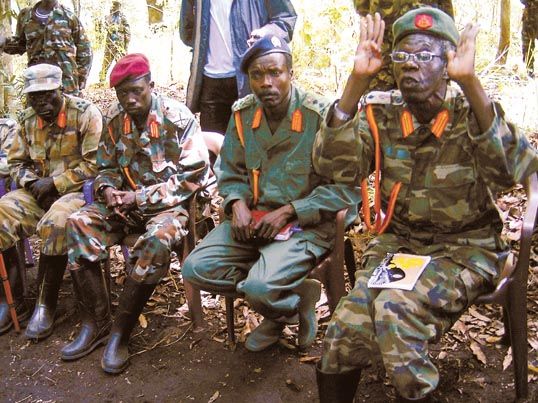

LRA leader Joseph Kony (second from right) and his second-in-command, Vincent Otti (far right), were both indicted by the ICC

Most of the academic and political attention that the International Criminal Court (ICC) receives these days comes from Sudan and Libya. There is little doubt that the investigations of Sudan’s Omar al-Bashir and Libya’s Muammar Gaddafi have captured the imagination of the Court’s fiercest advocates and most vehement critics alike.

It is no secret that the world’s attention can only be split so many ways. When our eyes and ears turn to Libya, we ignore Bahrain and Yemen. When we claim genocide in Darfur, we ignore the horrors of the Democratic Republic of Congo (DRC). Similarly, there is a significant division in the attention that the ICC’s cases get. Generally, the ongoing occurrences of war crimes and crimes against humanity in the DRC and the Central African Republic (CAR) are examined the least. The case of Darfur, thanks in large part to remarkably influential (if not always well-informed) activism of American human rights groups and celebrities as well as the labelling of the Khartoum regime as genocidal, remains a focal point of international political and media attention. Understandably, no case currently receives nearly the attention as Libya where a delirious tyrant, a former London School of Economics grad student and the Intelligence chief are in the cross-hairs of NATO bombs and the ICC’s Prosecutor. Somewhere, in the middle of the pack are the Kenya and Ugandan cases, with Kenya receiving more attention because of its recent nature.

Attention to northern Uganda from scholars, observers and international development community exploded in the early 2000s. A conflict which had long been neglected and seemingly relegated to oblivion, quickly became front-page news and emerged on the agenda of international institutions. This was in large part the result of the ICC’s involvement. In 2003, the situation in northern Uganda became the first case to be referred to the ICC, making Uganda “a litmus test for the much celebrated promise of global justice,” according to scholar Kasaija Phillip Apuuli. Two years later, the Court issued arrest warrants for the four senior members of the Lord’s Resistance Army (LRA): Joseph Kony, Vincent Otti, Okot Odhiambo, Dominic Ongwen and Raska Lukwiya.

Internationally, the ICC’s indictments were hailed as a historic moment symbolizing the end of impunity for violators of the gravest crimes. Locally, however, many viewed the ICC’s timing and intervention as precarious, if not dangerous.

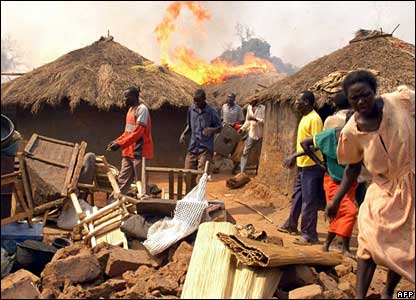

The conflict in northern Uganda resulted in, at times, millions of civilians being forced into internally displaced persons camps (Photo: BBC)

The notoriously brutal LRA, led by Kony, had been at war with the government of Uganda for two decades. Numerous peace initiatives had stalled or failed for various reasons. Then, in 2000, the Government of Uganda passed an Amnesty Act which guaranteed that any LRA combatants who defected from the LRA would be granted reprieve from prosecution and reintegrated into society. Justice would be achieved through context-sensitive traditional reconciliation mechanisms rather than through trials. When the ICC began its investigations and subsequently issued arrest warrants for Kony and the other top officials, many civil society, human rights and religious leaders in northern Uganda strongly criticized the decision. Tim Allen, who wrote a remarkably lucid account of “trial justice” in Uganda quotes one northern Ugandan human rights worker as saying: “There is a balance in the community that cannot be found in the briefcase of the white man.” Others, most thoroughly scholar Adam Branch, maintained that the Ugandan government was in effect using the ICC in order to justify and legitimize a military campaign against the LRA.

The discourses and debates in northern Uganda crystalized the apparent dilemmas of pursuing international criminal justice in the context of fragile peace processes. While the so-called (and poorly named) ‘peace versus justice’ debate emerged during the work of the International Criminal Tribunal for the Yugoslavia, the case of Uganda convinced many that the debate would become a permanent feature of discourses regarding international justice.

Many thought that progress towards peace was doomed by the ICC’s intervention. Yet, in a development that ran contrary to many observers’ gloomy prognoses, between 2006-2008, the LRA and the Government of Uganda held what many saw as the most promising talks regarding peace in northern Uganda since the conflict had started. Some, like Michael Otim and Marieke Wierda, thus suggested that the ICC’s warrants had acted as an incentive, not a disincentive, to peace negotiations and made it clear that accountability would have to be central to any negotiated solution.

While large-scale violence has stopped in northern Uganda, an official peace agreement remains elusive (Photo: Atlantic Star Productions)

As many observers point out, the negotiations, based in Juba, South Sudan, were all the more remarkable because, for the first time, issues of justice and accountability were negotiated between the warring parties. Indeed, an agreement between the LRA and the Government of Uganda on these issues was entered into. It combined traditional justice mechanisms with formal prosecutions, not through the ICC, but a special division of Uganda’s High Court. In turn, Kony was offered an amnesty and a guarantee that the government would work to ensure that the ICC arrest warrants were dropped.

Many issues plagued the talks. The size of the delegations on both sides was very large, a factor that is rarely seen as conducive to effective peace negotiations. The LRA delegation, in particular, may not have been representative of the LRA itself. It was formed, in large part, by members of the LRA Diaspora who had never fought in the conflict. There remain questions as to whether either the government or the LRA was truly committed to a negotiated settlement. It is possible that the LRA used the Juba negotiations’ ceasefire as an opportunity to move its forces from Sudan to the DRC. Likewise, there are suggestions that the government was only ever interested in a military solution to the war with the LRA. Both before and after the peace negotiations, the government held this view. The location of negotiations in the extremely under-developed Juba – likely because Sudan is not a ICC member-state and thus Kony would not be under threat of arrest if he attended talks – may not have been ideal. Of course, the ever-present ICC arrest warrants hung over the negotiations as well. One of the indicted LRA commanders, Vincent Otti vowed that he would “only sign an agreement that brings peace, not one that leads me to the International Criminal Court.” For whatever reason, or combination thereof, in the end, the delegates and the international community which had funded and organized the Juba peace talks waited in vain; Kony never showed up to sign the peace agreement.

The case of Uganda offers the best case study in understanding the real as well as the trumped-up tensions between peace and justice. It offers the best opportunity to illustrate the real decisions and dilemmas facing societies transitioning from brutality to peace as well as the false dichotomies and the fallacious ‘peace versus justice’ debate.

The experiences of northern Uganda have much to offer our understandings of the relationship between peace and justice, including how justice is treated at the negotiation table (Photo: dudelol.com)

More than any other case, that of northern Uganda can teach us a number of things: how issues of justice and accountability are actually treated at the negotiating table; how tensions between traditional justice mechanisms and formal, criminal justice are expressed and who is privileged by either form of justice; how different actors perceive the relationship between peace and justice differently and whether this is based on contrasting and competing conceptions of both justice and peace; how the decision to grant amnesties clashes with guarantees to prosecute; how local demands versus international obligations are often out of synch; and, perhaps least considered but most importantly, how attitudes and dilemmas of key actors change through time.

While Libya and Sudan receive the brunt of the world’s attention, by returning some of our focus to Uganda, we may be able see how peace and justice have been balanced and see whether any lessons can be drawn.

Of course, there is the ever-pressing need to not blindly apply the lessons of one situation across contexts. What fits and works in one case, doesn’t necessarily fit and work in another. As is often said: “there is no one-size fits all.” Nevertheless, the case of northern Uganda has much to offer to our understandings of peace and justice in other settings, including Darfur and Libya. Put simply, the lessons of northern Uganda today provide our best chance to get to the bottom of the ‘peace versus justice’ debate, expose its fallacies, and move beyond it.

This blog was cross-posted at International Justice Central.

Pingback: The ICC’s Arrest Warrant for Gaddafi: Justice, Peace and Politics Meet «

Pingback: Invisible Children (Participation) « IntrotoCES

Pingback: Viral Video Hopes to Spur Arrest of War Criminal | Streaming Media Hosting

Pingback: reflections on kony 2012 « life.remixed

Pingback: A Tiny Bit Of Caution |

Pingback: Stopping Kony, or stopping video activism? « Dochasnetwork's Blog

Pingback: Why I Don’t Support #Kony2012 | Journeys towards Justice

Pingback: Taking “Kony 2012″ Down a Notch

Pingback: ‘Kony 2012′ Threatens Lawsuit Against Online Parody - Gadsit Buzz

Pingback: Frosty News » ‘Kony 2012′ Threatens Lawsuit Against Online Parody

Pingback: It All Begins with Understanding | My Blog

Pingback: The Problem Is That It's Hard To Figure Out Exactly What Researchers Mean When They Talk About Online Sex Addiction - The Internet Nomad

Pingback: Third World Poverty: Uganda – Medical Anthropology