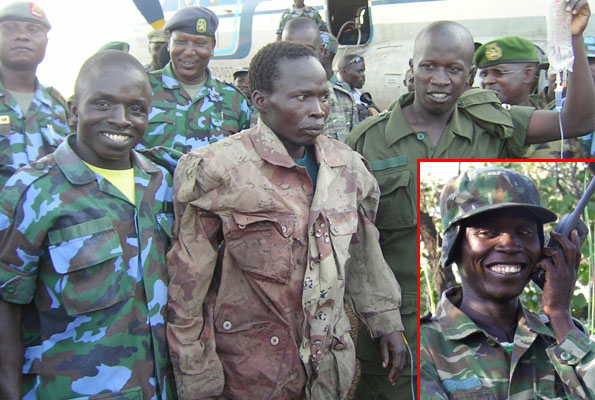

Thomas Kwoyelo, seen here after his capture, began his trial in Gulu on July 11 2011 (Photo: New Vision)

On July 11, I had the opportunity to attend some of the beginning of the first trial of Uganda’s International Crimes Division of the High Court, in Gulu, Northern Uganda. On the stand is Thomas Kwoyelo, a former senior Lord’s Resistance Army combatant. He is being tried on 12 counts and 53 charges dating between 1996 and 2009. So exhaustive is the list that it took almost two hours to read out as Kwoyelo stood subdued and at times appearing exhausted. A legal observer suggested that the prosecution “piled on” the charges against Kwoyelo in order to guarantee he is convicted on at least some counts, given that it will be difficult to prove many of the charges.

The trial began rather oddly. There were hundreds of people awaiting Kwoyelo’s appearance at the Court. He came in on a convoy. The first truck was filled to the brim with police officers and other alleged criminals heading to the Court. An extraordinarily odd moment unfolded with the presence of a marching band (see below). Here’s a clip of his arrival:

The International Crimes Division of Uganda’s High Court was set up in the wake of the Juba Peace Talks (2006-2008), the latest attempt to resolve the seemingly intractable conflict between the Lord’s Resistance Army and the Government of Uganda. In the context of widespread fears that LRA leader Joseph Kony would not sign the peace agreement unless the ICC arrest warrant against him was dropped, the International Crimes Division was viewed as an institution which could circumvent the need to bring LRA leaders to the ICC. In the end, however, Kony refused to sign the final Juba Peace Agreement. Nevertheless, the Government of Uganda moved forward and established the Division. Kwoyelo, who was captured in 2009, is the Division’s first defendant.

The biggest controversy at the trial has to do with whether or not Kwoyelo should receive amnesty. In 2000, the Government of Uganda passed the Amnesty Act which was intended to provide protection from prosecution as an incentive to LRA combatants who defected. The record of the Amnesty Act remains uncertain – some say it has been effective in getting LRA combatants to defect; others disagree. It has been a rather confused process. Those “most responsible” for atrocities in the LRA, including Joseph Kony, have been offered full amnesty by the government only to have it revoked and then offered again.

Kwoyelo’s defense counsel argue that he should be granted amnesty. Kwoyelo has applied to Uganda’s Amnesty Commission and many believe there is no legal reason to bar him from receiving amnesty which does not stipulate that anyone should be excluded. In other words, it is a blanket amnesty. However, to date, he has not received a verdict and his application is “pending”. Further complicating matters is that other LRA members with higher seniority in the rebel group have successfully received amnesty. Caleb Alaka, Kwoyelo’s chief Defense Lawyer argued:

“High officers in the LRA…were granted amnesty. Since the brigadiers were granted amnesty, the denial by the directorate of public prosecutions…infringes on [Kwoyelo’s] constitutional rights to fair treatment.”

In other words, by trying Kwoyelo while amnestying others, Kwoyelo’s defense raises the specter that this constitutes a violation of the constitutional guarantee of equality before the law. If the judges at the trial decide that there is a constitutional issue with his amnesty application, the issue will be referred to the Supreme Court of Uganda which would, presumably, have to adjudicate who, specifically, is admissible under the amnesty.

Exacerbating the controversy is that the Directorate of Public Prosecutions (DPP) noted in Alaka’s statement is the same body adjudicated Kwoyelo’s amnesty application.

Thomas Kwoyelo with his lawyer at the first hearing of the International Crimes Division of the Ugandan High Court in Gulu (Photo: Moses Akena)

Some will say this argument is irrelevant because amnesty laws for international crimes run contrary to the international duty and obligation to prosecute. That is not so clear, particularly in this case. Kwoyelo is not one of the LRA commanders sought by the ICC. Further, despite the high rhetoric of human rights groups, as numerous legal scholars have pointed out, the international duty to prosecute may be crystalizing but has not yet crystalized. Amnesties continue to be used as much, if not more frequently, in negotiated peace settlements and, to quote the renowned legal academic Michael Scharf on this issue:

“a ‘rule’ that is so divorced from the realities of State practice…cannot be said to be a binding rule at all, but rather an aspiration.”

To date, the international community has not vehemently demanded that other captured LRA leaders like Brigadiers Sam Kolo and Kenneth Banya, who have received amnesty, must be prosecuted. It is unclear why Kwoyelo should be treated substantially differently than either Kolo or Banya. More specifically, if Kwoyelo’s case is unlike others and the Government feels he must be prosecuted, the reasons for denying him amnesty and thus necessitating his prosecution must be made clear to him and his defense. Indeed, you would think this should happen before his trial.

There are numerous other interesting dynamics to consider during this trial that both international lawyers and conflict resolution observers should be keen to keep an eye on. For lack of time, I will briefly consider two.

First, Kwoyelo’s charges are based on violations of Uganda’s 1964 Geneva Conventions Act. The Act requires that the violations be done in the context of an international conflict, understood here as a conflict between two or more states. In order to demonstrate that Kwoyelo’s acts occurred in the context of an international conflict, rather than a civil war, the prosecution may have to provide evidence that external actors were directly involved in the war. In order to do so, the prosecution would presumably have to illustrate that the government of Sudan was a party in the conflict. While it is clear by now that Khartoum used the LRA as a proxy group against Southern Sudan’s SPLM/A, the Government of Uganda has never produced direct evidence of it.

Second, the trial – if conducted fairly and legitimately – will certainly set a key precedence for international criminal justice as it relates to Uganda. In 2008, the ICC rejected an admissibility case to have the Court’s warrants against Kony and other senior LRA members dropped. While one trial may not be sufficient, if the International Crimes Division can successfully try LRA combatants, attempts to challenge the ICC’s warrants may receive new life.

The next hearing in the trial is scheduled for July 25th, when the issues raised by the defense will be considered and adjudicated. While many are seeking a “speedy” trial, it seems unlikely that this will not be a drawn-out affair. While it is unclear whether he chose to do so voluntarily or not, Kwoyelo stood for the entire four hours of his court date yesterday. He may have to stand for many, many more hours to come.

I will leave readers with this, the oddly celebratory scene, outside the High Court in Gulu, after Kwoyelo entered the court to await his hearing:

Note: an earlier version of this post incorrectly stated that Kwoyelo has twice applied for amnesty. He has only applied once.

Great post, Mark. I really had not much idea of this trial in particular.

Seems to me as though the Uganda government was previously much more interested in ending the civil conflict and all the attendant atrocities rather than in establishing a robust and fool-proof approach to prosecuting individual people who may have done ‘war crimes’ or just ordinary crimes under the cloak of their movement. This all seems very inadequate and oddly inconsistent by Western justice standards. This commender here, as bad of a person as he might be, is certainly not getting a fair trial, from the description of the process. I think most of Africa is not ready to carry out these kinds of justice proceedings…look at Rwanda where many of the perpetrators of killings in 94′ were simply warehoused in makeshift prisons, then many were released and only some received a serious trial and a fitting sentence. For someone like me who doesn’t have a legal background, I can’t even tell whether these countries’ systems stem from the British common law or from the Napoleonic code (Uganda might be British-influenced, I guess). Good on them for trying, though, since the alternative would have been some kind of a lynching.

Pingback: ‘5 Religious Organizations’ Updates « Nanobots Will Enslave Us All

Does anyone know if the prosecution is basing its denial of amnesty to Kwoyelo based on customary international law, and if so, what in particular is its argument? Or does anyone know what arguments could be made for denial of amnesty based on customary international law? Thank you for any feedback.

Thanks for your comment Sharon.

I attended parts of two Kwoyelo hearings – one at the International Crimes Division of the Ugandan High Court and one in the Supreme Court once the issue of the amnesty law was referred to it. In neither cases, as far as I could tell, did the prosecution or defense bring up customary international law on the issue of amnesty. The defense focused on two issues: one, that as a blanket amnesty, Kwoyelo was entitled to receiving amnesty; and two, that Kwoyelo had been tortured while in prison. The defense argued that both the denial of amnesty to Kwoyelo and torture were unconstitutional and so the case should be thrown out. The Prosecution decided that it would declare the entire amnesty unconstitutional. By doing so, they hope that the whole Amnesty Law is thrown out and therefore Kwoyelo (and others) can be tried. Importantly, however, they argue that the amnesty runs against the constitution not against customary international law.

I am not a lawyer, but I think it would be difficult to make a case against a domestic amnesty for a case such as Kwoyelo’s by relying on international customary law. Had he been wanted by the ICC and thus was deemed “most responsible” or had he been charged with genocide or torture (where a clearer duty to prosecute exists), it’s possible that a customary law argument would have been used. It’s important to remember, however, that international law on the use of amnesties is still crystalizing. In a 2005 ruling at the Special Court for Sierra Leone, the judges themselves declared that customary law was “crystalizing not crystalized”. I also suggest, if you’re interested in the issue of amnesties and their use, to read Louise Mallinder’s ‘Amnesty, Human Right and Political Transitions’ and Mark Freeman’s ‘Necessary Evils’ work on the subject.

Sharon – I also suggest that you read Patrick Wegner’s piece here at JiC on the possible implications of the Kwoyelo trial: https://justiceinconflict.org/2011/09/12/squashing-the-amnesty-law-in-uganda-possible-implications-of-the-kwoyelo-trial/#comment-620

Pingback: Kwoyelo Amnesty Raises Questions about Ugandan Justice

Thanks Mark for keeping those blogs coming, i always look forward to the next one each day. I recently started following up on Kwoyelo’s case simply because my new job requires me to understand the process and I can hardly ignore the temptation to read one after the other.

Well, my only issue so far with Kwoyelo’s case is government! Its almost impossible to accurately draw a line between the powers of the judiciary and government. In the first place, government had a duty to protect Kwoyelo as a child from the LRA abduction and provide him an atmosphere that other Uganda children enjoy when growing up. Given that Kwoyelo was abducted at the age 13 when going to school, there is no doubt that it’s the LRA system that shaped him into the ‘criminal’ he is today. And it is only unfortunate that the government is turning against him by using its failure to offer him protection when he was a child and instead choose to prosecute him for crimes he would not have otherwise committed if government had played its role.

Pingback: 5 Religious Organizations You Should Hate Update « Atheist Hobos

Pingback: The Kwoyelo Trial :Resolution:Possible

Pingback: The Kwoyelo Trial: Sorting out this Amnesty Business :Resolution:Possible

Pingback: The latest twist in the case of Thomas Kwoyelo | Beyond The Hague