Gillian McCall, a London-based researcher in international criminal law, joins JiC with a fascinating guest post on the question of whether trials in absentia are legitimate and legal. Gillian offers a glimpse into how the various international tribunals have treated the question of trials in absentia, concluding that the continuing absence of defendants before tribunals is an issue of politics, not law.

Courtroom chamber at the International Criminal Tribunal or the Former Yugoslavia (ICTY) (Photo: Klaasjanb)

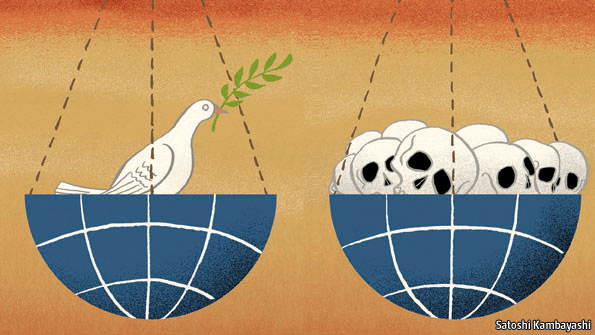

International criminal courts have become famous — or infamous — in some quarters for their perceived inability to quickly capture and try those accused of serious crimes. Ratko Mladić, accused of genocide, spent 16 years on the run before his capture; Radovan Karadžić did so for twelve. At the ICC, Omar al-Bashir remains at large four years after his indictment, and Joseph Kony remains famously out of reach of the Court, over 6 years after being indicted. Why, critics ask, could their trials not have begun while they were on the run? Could trials in absentia be the way to rid international criminal law of unnecessary lengthy delays?

In the UK, the idea of conducting trials in the absence of the accused seems like an assault on the most uncontroversial of liberties. But elsewhere in the world, such trials are a far more common occurrence: one of the world’s newest international criminal tribunals, the UN Special Tribunal for Lebanon, even allows for it explicitly in its statute. This February, days before the seventh anniversary of the assassination of Hariri, the STL announced that the trials of the four accused would go ahead in their absence. Is this a step too far for international courts, or is there good reason to carry on without the accused?

The motive behind the STL’s decision is obvious; delays frustrate justice. Allowing for trials in absentia will either deter the accused from evading the court, forcing the accused to submit to the court to defend themselves; alternatively, it will allow trials to go ahead in the absence of the accused, meaning that justice won’t be frustrated by unnecessary delays in an international system with no police force, reliant on reluctant states to hand over defendants.

The STL is the first international court to allow for trials in absentia since Nuremberg, and even at Nuremberg only one of the top 24 defendants was actually tried in absentia. The STL is unique in many ways, though, and brings the issue of absentia trials into sharp focus. Although the court is international, the statute is based on Lebanese law, Lebanon being a country which allows for trials in absentia in any event. It is also limited in jurisdiction: unlike other international or hybrid courts whose jurisdiction lasts a number of years with many, many accused, the STL was set up to try one single event, although there are now a series of connected cases. Its defendants, though, have avoided trial for over seven years. The court, in the meantime, has nothing to do, no other cases that it can pursue, and no investigations it can be getting on with. To be left in suspension would be to hemorrhage money — not to mention waste huge amounts of time and effort — for no apparent reason.

But what about the defendants’ rights? At the ICTY, the Blaškić Appeals Chamber stated that:

“…it would not be appropriate to hold in absentia proceedings against persons falling under the primary jurisdiction of the International Tribunal…Indeed, even when the accused has clearly waived his right to be tried in his presence…it would prove extremely difficult or even impossible for an international criminal court to determine the innocence or guilt of that accused”

The crater left after the assassination of Lebanese Prime Minister, Rafik Hariri, in 2005 (Photo: AP)

This gets to the crux of the issue; how can a court determine culpability on hearing only half the story? While defence lawyers might be appointed to test the prosecution evidence, this must be a difficult task without instructions from the accused, never mind the impossibility of actively putting forward their individual defence case. The recent ICC judgment on Lubanga has demonstrated the absolute importance of mounting a strong defence, without which the prosecution’s use of false evidence via intermediaries may not have been discovered. A trial without a defence seems to be a process which does not tend towards finding out what happened, or bringing accountability for it.

Moreover, trials in absentia damage international justice as a whole, seeming to provide prosecutorial soapboxes which probably make defendants less likely to submit to the court. They also vindicate those critics who call international tribunals ‘biased institutions’ which have the sole aim of publicising the guilt of the losing side of a conflict.

In absentia proceedings do not necessarily breach human rights, though. The ICCPR Article 14 makes guarantees for minimum standards for defendants, including:

“(d) To be tried in his presence, and to defend himself in person or through legal assistance of his own choosing; to be informed, if he does not have legal assistance, of this right; and to have legal assistance assigned to him, in any case where the interests of justice so require, and without payment by him in any such case if he does not have sufficient means to pay for it;

(e) To examine, or have examined, the witnesses against him and to obtain the attendance and examination of witnesses on his behalf under the same conditions as witnesses against him;”

Defendants cannot be barred from being able to defend themselves including examining witnesses, but there is nothing to say that their presence is required to do this. They cannot be stopped from going to court and the trial cannot go ahead in their absence if they wish to be present, but their presence is not necessarily required if they don’t want to attend. The Human Rights Committee has even stated that trials in absentia may be allowed, if there is adequate and timely notice of the trial and there is a request for the attendance of the defendant.

The European Court of Human Rights, too, has considered that a trial in absentia does not necessarily breach the rights of the accused:

“neither the letter nor the spirit of Article 6 of the Convention prevents a person from waiving of his own free will, either expressly or tacitly, the entitlement to the guarantees of a fair trial,” although the Court does comment that there are a number of fair trial rights “and it is difficult to see how [a defendant] could exercise these rights without being present.”

There have been occasions where defendants at international courts have expressly waived their right to attend, for example Jean-Bosco Barayagwiza at the ICTR and Augustine Gbao at the Special Court for Sierra Leone, who both stated that they did not recognise the courts and so would not attend their own trials, despite being in custody. In the case of Gbao, the Trial Chamber ruled that he had expressly waived his right to be present and that the court would continue the case against the three defendants. The Chamber commented that

“trial in the absence of an accused person is an extraordinary mode of trial, yet it is clearly permissible and lawful in very limited circumstances.”

The Special Court for Sierra Leone statute mirrors the ICCPR in this regard at Article 17(4)(d), but there is the addition of Rule 60 of the Rules of Procedure and Evidence of the Court which provides that a trial may only continue in the absence of the accused if he or she has first made an initial appearance at the court. This outlines that a waiver of a right to attend might be implied as well as expressed. A trial can also continue without a defendant who has been removed for being disruptive, after a warning.

This allows trials to continue in the face of a difficult defendant, but does not solve the problem of defendants on the run. The ICTY addresses this problem in a different way: Rule 61 of the Rules of Procedure and Evidence allows the court — if the arrest warrant has not been executed within a reasonable time — to request submission of the indictment to the trial chamber, together with the evidence which was before the judge who confirmed the indictment. The prosecutor may call witnesses, and the Trial Chamber may also call for witnesses to give evidence. The Trial Chamber then determines if there are reasonable grounds for believing that the indicted crimes have been committed. Such a hearing was held for Karadžić and Mladić in 1996 — some twelve years before either was arrested — and reconfirmed their indictments.

This procedure is not a true trial in absentia, as there is no final binding decision given as to guilt; if and when the suspect is apprehended and extradited to the court, proceedings are reopened. It may appear to provide a compromise — and indeed it was originally a compromise between civil and common law tradition states who disagreed about absentia provisions — as it does facilitate a quasi trial-like procedure that allows some victims to be heard and can confirm to interested parties the seriousness with which the cases are being dealt.

However, it appears to be little more than the prosecution talking shop. Tthe accused is obviously not involved and no appointed counsel for the defence is able to test evidence or put forward their case. In the case of Karadzic and Mladic, both of whom are now on trial, their cases were dealt with in an incomprehensibly short amount of time — less than two weeks.

The fact that defendants don’t submit to the Court isn’t, in fact, a legal issue, so the fact that there is no adequate legal solution makes sense. This is a problem of law enforcement, or the lack thereof, in the international system. The courts rely on states to hand over indictees and it is in this mechanism that there is failure — states often protect those with ICC arrest warrants, until it is politically inconvenient e.g. Mladic was essentially exchanged for EU membership by Serbia. The solution lies in politics rather than law and the focus should be on getting states to engage and cooperate with international courts in order to arrest the accused. Courts need to wait, patiently, until this happens.

Interesting article, it would have been nice though to hear about the arguments that made the ICC (or rather the States Parties) decide to not conduct trials in absentia. As far as I am informed the Rome Statute does not allow for them.

Beautifully written by Gillian McCall. However, the short piece heavily stands on Anne Klerks’ (published) Master’s Thesis from 2008 (Ll.M. Tilburg), and should at least acknowledge this heritage. It’s considered good scholarly style to name sources.

And Patrick Wegner’s concern is addressed and fully answered on pp. 38-40 of said thesis.

The ICC’s trial chamber V(a), by their majority, also missed Klerk’s thesis. Much to the disadvantage of their weak but loquacious decision of 18th June 2013 ( http://www.icc-cpi.int/iccdocs/doc/doc1605793.pdf ). Application for leave to appeal has been submitted by the Prosecution.

Olga Herrera Carbuccia’s dissenting opinion ( http://www.icc-cpi.int/iccdocs/doc/doc1605796.pdf ) had only one tenth of its size, but was MUCH better and indeed compellingly clear. Experienced readers sense where wordiness is used to cloak legal deficits.

Pingback: Much more to be done before MH17 findings can support a war crime trial | Em News

Pingback: Much more to be done before MH17 findings can support a war crime trial - Australia News |The Today Post

Pingback: Lockerbie experience is no model for the effective prosecution of MH17 bombers - News blog

Pingback: Lockerbie experience is no model for the effective prosecution of MH17 bombers | Em News